Data-Driven Advocacy on the Lower Deschutes River

Like many freshwater environments, the Deschutes River in Oregon is under pressure from development, pollution, and climate change. Many rivers, streams and lakes in the Deschutes Basin do not meet Oregon water quality standards–where state water quality monitoring assesses levels of bacteria, pH, dissolved oxygen, temperature, and fine sediment.

Hannah Camel is the Water Quality Coordinator for the Deschutes River Alliance (DRA), a non-profit organization that focuses on the health of the lower 100 miles of the Deschutes River–the area most affected by human intervention.

As a data-driven organization, the DRA has benefited from the installation of two NexSens X2 data loggers. Camel explains that these have given the team “better data and more scientifically credible data,” adding weight to their work advocating for colder, cleaner water, healthy ecosystems, and the recovery of fish life in the Lower Deschutes River (LDR).

NexSens X2 data logger setup. (Credit: DRA)

The Lower Deschutes River

The 252-mile-long Deschutes River originates from Little Lava Lake, Oregon, on the eastern slope of the Cascade Mountains, and empties into the Columbia River. It is the basis of most of Central Oregon’s economic and recreational activities.

In the mid-20th century, the Deschutes River was fragmented by the Pelton-Round Butte Hydroelectric Project. The three-dam complex comprises Round Butte Dam, Pelton Dam, and a final, re-regulation dam.

The LDR begins at the tailrace of the downstream-most dam and runs 100 miles north to its confluence with the Columbia. It is an Oregon Scenic Waterway and Federal Wild and Scenic River, world-renowned for its fly fishing, and visited by thousands of people each year.

Raft on Lower Deschutes River. The LDR is a popular destination for recreation from fly fishing to multiday rafting trips. (Credit: DRA)

The Impact of Human Intervention on the Lower Deschutes

The hydroelectric facilities on the LDR are the only ones in the United States jointly owned by a utility company–Portland General Electric–and a tribe–the Confederated Tribes of Warm Springs. Following relicensing in 2004, the groups committed to working together to restore fish passage.

Consequently, in 2009, a Selective Water Withdrawal (SWW) tower was built in Lake Billy Chinook, the main reservoir in the system, and held behind Round Butte Dam.

The SWW Tower is engineered to help migrating smolts find their way through the lake and hydroelectric complex. Operators can release up to 100% of surface water at any time and for an unlimited duration–doing so generates surface currents that attract the fish to a collection facility.

While the SWW has successfully increased the number of anadromous fish leaving the hydroelectric complex, it has also had significant negative side effects.

The SWW Tower draws water from Lake Billy Chinook, a reservoir fed by three tributaries–the Metolius River, Middle Deschutes, and Crooked River.

Notably, the Metolius brings very cold, very clean water, and the Crooked River brings very warm, nutrient-laden water from nearby agricultural hotspots–it’s estimated that the Crooked River accounts for 86% of Lake Billy Chinook’s dissolved nitrates. The difference in water temperature in these tributaries leads to stratification in the lake.

Camel explains, “Now they’re drawing this warm nutrient-rich Crooked River water from the surface, combining it with the bottom water, and we’re seeing huge water quality issues downstream because of that.”

Algae blooms in Lake Billy Chinook in a popular swimming area. (Credit: DRA)

A Changing Aquatic Ecosystem

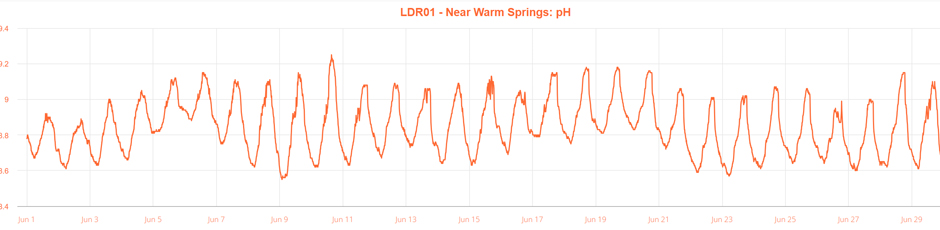

Changes to water quality were noted by the DRA almost immediately after the SWW Tower began operation. Camel outlines, “We have seen an increase in temperatures and pH in the lower river. We’ve seen issues with dissolved oxygen.”

A 2023 study found that “temperature predominantly drives daily DO [dissolved oxygen] dynamics in the contiguous United States,” highlighting the potential ecosystem damage the release of warm water could cause in the LDR.

“The overarching issue that we’re seeing is a huge increase in nutrients and algae in the lower river […] This non-usable form of algae is proliferating and pushing out all the species that are usable by our benthic communities,” Camel continues.

While the negative impact on water quality was immediately apparent, Camel warns that “we’re just now starting to see a lot of those effects on wildlife. We are seeing shifts in hatch timing of insects, and some insect species are gone entirely. It is speculated that this could affect the timing of our Redband Trout spawning.”

Camel is clear that the DRA isn’t outright against the SWW Tower, instead advocating for a measured, data-driven approach that balances supporting fish migration without harming the LDR’s fluvial ecosystem.

She states, “We’re pushing for more cold bottom water being released into the lower Deschutes River for the majority of the year–versus how it is now, where it’s a majority surface water being dumped in. With the exception of peak out migration to encourage smote capture, but releasing that water at night so it’s already cooler.”

Selective Water Withdrawal Tower on Round Butte Dam. (Credit: DRA)

A New Way to Monitor the Lower Deschutes River

Robust scientific data is fundamental to the DRA’s mission and provides a vital record of the changes unfolding in the LDR. However, until 2016, the team used resource-intensive manual monitoring systems.

“We were doing a lot more grab sampling with manual temperature loggers,” states Camel. “All they can monitor is temperature and you have to physically be there to plug them in to download the data. They have a really short capacity.”

In 2016, the DRA team installed two NexSens X2 data loggers, one about a mile below the final dam and one at mile 50, halfway between the final dam and the LDR’s confluence with the Columbia. The real-time data provided by these loggers complements the team’s ongoing grab samples and targeted studies.

Camel explains that the DRA “focus on long term monitoring of temperature, dissolved oxygen, pH and nutrients, to give us a picture of how operation changes at this [hydroelectric] complex have affected the lower river’s ecosystem.”

She highlights that the X2 water quality systems–which integrate the X2 data logger, mounting kit, and solar power pack–have proved to be an effective solution. “They’re very durable and reliable. We’re in a challenging ecosystem in the high desert, it’s extremely hot, it’s extremely cold, and we’ve had no issues with them,” states Camel.

The DRA uses the YSI EXO data sondes, which are easily plugged into the X2 data logger. “They’ve integrated extremely well with our existing equipment,” she adds. “We’ve had zero issues putting them together and making this system, which saves us time and money and effort.”

Field Equipment used by the DRA. YSI EXO2 sonde, NexSens X2 data logger, and field cables. (Credit: DRA)

Transforming Monitoring on the Lower Deschutes River

Better data has been transformative to the organization’s work. Camel explains, “The more intensive monitoring has been done since 2016 and that’s allowed us to build this really big, long term data set.”

“We’re able to log every 10 minutes. I’m able to be at home and see how my sensors are running. It lets us respond in real time and then push those messages out immediately. Rather than having to wait six or eight months to process all this data, we’re able to put it out to the public and say we just saw a huge change in the lower river.”

Having high-quality, high-resolution, continuous data like this is rare. “No other group has a long-standing data set over the course of 10 years, and this has really helped us inform our advocacy efforts. We push for science-driven policy changes, not just policy changes,” elucidates Camel.

The data the DRA collects feeds into broader monitoring efforts, including data published by the Oregon Department of Environmental Quality.

Camel notes, “Because no one else is doing this monitoring in the lower river, we submit a lot of our data to them, and then they make it available for the entire United States.”

Graph of pH in the Lower Deschutes River at DRA monitoring site. Source: Nexsens WQData Live dashboard. (Credit: DRA)

The Future of Monitoring

Camel argues that more data is needed to deepen understanding of the environmental changes unfolding in the LDR, and the impact of the SWW Tower is one element in a complex patchwork of environmental flux, including climate change, industry, and development.

“We have plans to add a third monitoring location this year,” she says. “We want to put it right by where the mouth is with the Columbia so we can really get a big picture along the entire length of the river and understand exactly how dam operation affects it immediately downstream and all the way up to the mouth.”

“We also are in the process of developing a new algae monitoring initiative. We want to assess biomass, species composition, and nutrient impacts on the lower river, and we want to build this data set now so if and when operational changes are made, we can start looking at how operation will change the nuisance algae community,” she continues.

Thinking bigger, the DRA has ambitions of monitoring at a watershed-wide level, “We understand the health of that river is the sum of its tributaries,” Camel notes. “We want to start monitoring more tributaries coming in, both on the lower river and on the upper–particularly those three coming into Billy Chinook–and look at restoration strategies, especially on the Crooked River.”

Aerial photo of Round Butte Dam. (Credit: DRA)

Advocating for a Healthier Deschutes

Like many rivers in the US and around the world, the LDR is experiencing accelerated change, in large part because of human activity. It is certain that data collected by the DRA–which contributes to wider monitoring efforts–will continue to be integral to informing and observing positive environmental change.

“There’s an issue going on, and we wouldn’t be arguing for change if the data didn’t show that,” Camel concludes.

0 comments