Cascadia Fault Study Helps Scientists Learn Why Faults Break

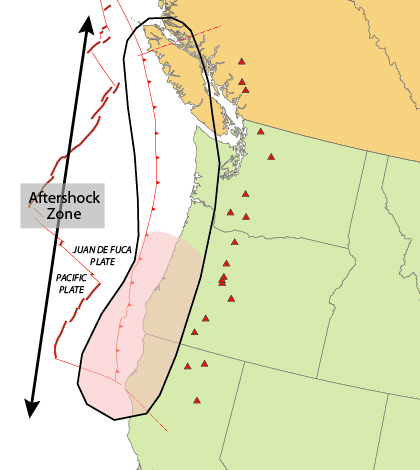

Cascadia subduction zone. (Credit: USGS)

An investigation by scientists at the University of Washington has uncovered effects of gravity from the sun and moon on the Cascadia fault that runs beneath the Pacific Northwest, according to a release.

Research into the fault is important because it is one of the most active in the United States, with a 6.6-magnitude earthquake occurring deep underground along the fault line each year. Results of the work will inform understanding of the Cascadia fault and reveal more about why faults break worldwide. The findings are especially relevant following the massive earthquake that struck Nepal in April 2015.

Investigators used tidal forces as one metric to survey the movements made by the Cascadia fault, with scientists correlating seismic activity with tidal events. They also focused on frictional forces that occur deep underground and found that those forces are very small.

“I was able to tease out the effect of friction and found that it is not the friction of normal rocks in the lab – it’s much lower,” said Heidi Houston, professor of Earth and space sciences at the university, in the release. “It’s closer to Teflon than to sandpaper.”

The Cascadia subduction zone, where a heavy ocean plate sinks below a continental plate. (Credit: University of Washington)

Going along with those low forces is the discovery of a new form of fault behavior that scientists are calling slow-slip. With the realization of the low-friction forces, they were able to expand their investigation into the earthquakes that come from slow, slipping faults.

Researchers looked at six recent slow-slip events that took place along the Cascadia fault’s subduction zone using seismometer data. They found that the slow quakes often occur every 12 to 14 months and are associated with underground tremors that travel about 5 miles from the zone for several weeks.

Every part of the Cascadia fault is affected by the vibrations. Tidal events have so small an effect on the fault that they’re not capable of causing a quake, scientists say. But pinpointing what effects they do have provided more information on processes that can’t be studied in a laboratory.

“Understanding slow slip and tremor could give us some way to monitor what is happening in the shallower, locked part of the fault,” said Houston, in the release. “Geophysicists started with the picture of just a flat plane of sandpaper, but that picture is evolving.”

Top image: Cascadia subduction zone. (Credit: USGS)

0 comments