CDC: Drinking Water At Fault in Hundreds of Illnesses and 13 Deaths in 2013 and 2014

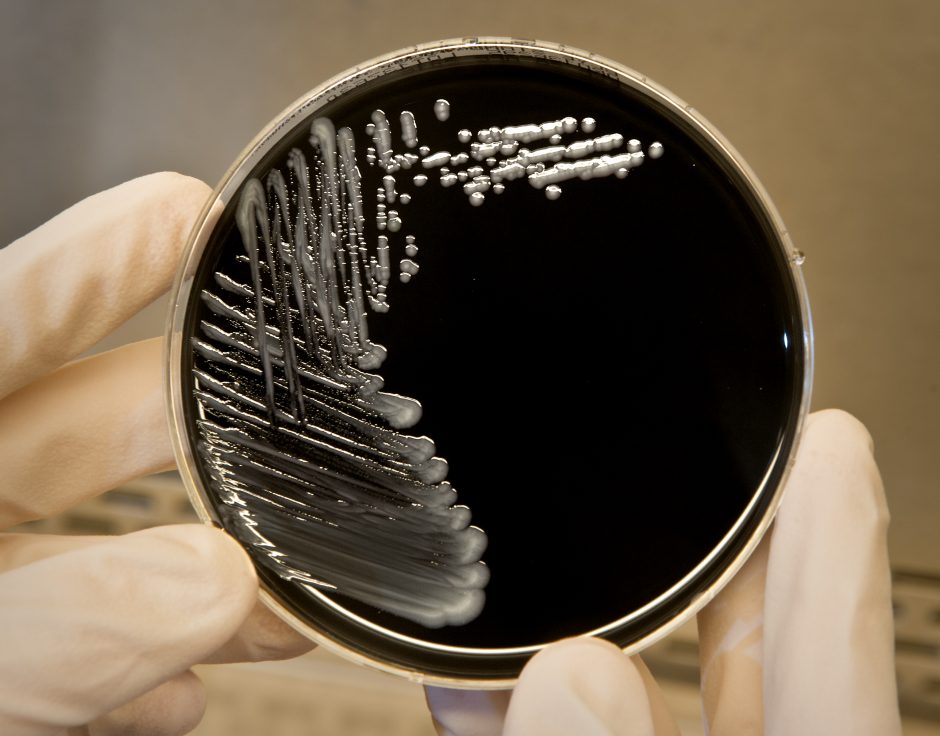

Legionella pneumophila, a bacterium that can cause Legionnaires’ disease, growing on specialized microbiological media (BCYE). (Credit: CDC.)

In November, the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) released two reports that may point to a growing contamination problem in American drinking water. The first report is called, “Surveillance for Waterborne Disease Outbreaks Associated with Drinking Water — United States, 2013–2014,” found here, and the second is titled, Waterborne Disease Outbreaks Associated With Environmental and Undetermined Exposures to Water — United States, 2013–2014,” found here.

The first of the reports indicates that in 2013 and 2014, chemicals, pathogens, or toxins caused 42 distinct drinking-water-associated outbreaks in 19 states which were then reported to the CDC. (Obviously there may have been others which went unreported.) Even more troubling: these reports do not include cases of lead contamination such as those seen in Flint, Michigan, so these higher numbers exclude that case and cases like it.

The fallout from these outbreaks included at least 1,006 cases of illness, 124 of which were serious enough to result in hospitalization. There were also 13 deaths reported. These numbers included cases in Alaska, Florida, Arizona, Idaho, Kansas, Indiana, Michigan, Maryland, Montana, North Carolina, New York, Oregon, Ohio, Rhode Island, Pennsylvania, Virginia, Tennessee, West Virginia, and Wisconsin.

Dr. Kathy Benedict, an epidemiologist and doctor of veterinary medicine, an expert in parsing out how zoonotic diseases like West Nile virus can “jump” between humans and animals, was the corresponding author on one of the reports from the CDC. Dr. Benedict highlights the difficulties inherent to parsing out whether these higher numbers mean more infections, better surveillance and reporting, or perhaps both.

“We do not know how many of the additional outbreaks this cycle were reported due to an actual increase in disease versus better reporting, versus changes in capacity in states to do surveillance,” Benedict explains. “Outbreak reporting varies among states, and these data may not present an accurate picture of waterborne disease outbreaks in a given state or overall.”

Drinking water outbreaks in focus

However, regardless of the trend, the numbers themselves are critically important.

“We do know that data likely do not capture all of the outbreaks or cases that occurred during this time,” Benedict cautions. “Outbreak surveillance data play a critical role in waterborne disease prevention, so continued support of current surveillance and efforts to increase capacity of waterborne disease surveillance is important for understanding the cause of water-related illnesses. We need these data so threats to safe water can be addressed.”

According to the CDC, Legionella triggered 57 percent of the outbreaks, 88 percent of the hospitalizations, and every one of the 13 deaths. Legionella, a type of bacteria, causes the potentially fatal respiratory illness Legionnaire’s disease, as well as Pontiac fever, a less severe variation of the disease that does not include pneumonia. Symptoms of either form of legionellosis include cough, fever, headache, muscle aches, and shortness of breath.

Cooling towers, which are often part of the air conditioning systems of large buildings, are a common source of Legionella exposure in outbreaks. Cooling towers need to be properly maintained in order to prevent Legionnaires’ disease. (Credit: CDC.)

Legionella bacteria are ubiquitous in the environment all over the world. They can contaminate drinking water when it is kept warm and stagnant, although the bacteria itself is inhaled once it is aerosolized, so cooling systems can also infect people in urban settings. Although water treatment schemes typically chlorinate water, sometimes that chlorination is insufficient to last throughout the system, and does not reach distant use points, allowing the Legionella to survive.

Cryptosporidium and Giardia, parasites that cause diarrheal illnesses, were also responsible for another eight outbreaks total in the CDC reports. Also during the time period covered, a first in two places: toxic algal blooms caused outbreaks in Carroll Township and Toledo Ohio, in 2013 and 2014, respectively. 15 more outbreaks were caused by environmental exposures to contaminated water.

The causes of 12 additional outbreaks remained undetermined—although those outbreaks were responsible for 63 illness, 39 hospitalizations, and eight deaths in eight states. Undetermined exposures could mean anything from unreported spills of toxic chemicals to undetected parasites or bacteria.

According to the CDC, 75 percent of the more than one thousand illness were connected to government-regulated community water systems.

Legionella in our water

Many see aging infrastructure as part of the problem. According to the American Society of Civil Engineers (ASCE), the overall “grade” for American infrastructure, including plumbing and water treatment systems, is D+. The drinking water grade standing alone is a D, and the American Water Works Association states that about $1 trillion will be needed just to maintain existing service and expand to meet growing demands within the next 25 years. Moreover, as extreme weather events happen more frequently, the strength of water infrastructure is likely to be tested more rigorously. Dr. Benedict stresses the importance of proper investment and preparation.

“There’s no evidence that aging infrastructure systems or extreme weather events have driven the difference between the last reporting cycle and this one,” Dr. Benedict clarifies. “However, treating water to remove contaminants, like chemicals, or kill germs and safely distributing it to consumers is critical to make sure that water is safe to drink.”

Obviously Legionella bacteria are a major problem, especially in urban areas. Although water systems can chlorinate to treat for these bacteria before they distribute water, these protocols may be inadequate to the task of completely eliminating the bacteria all the way to the use point.

“Once water enters a building, the key to preventing Legionnaires’ disease is to prevent Legionella colonization or growth in the building’s water systems,” Dr. Benedict explains. “When there is a reduction in disinfectant levels in your building water systems, or inadequate filtering, heating, or storing processes, Legionella can grow. There are many factors that can lead to Legionella growth, including: construction, breaks in the water main, changes to municipal water quality, biofilm, sediment, scale, fluctuations in water temperature and pH, inadequate disinfectant levels, changes in water pressure, and stagnation.”

Fortunately, there are steps to take in the fight against Legionella, building by building.

The water supply of any given building may need supplemental disinfectants over the long-term in the water to increase disinfectant levels and help stunt the growth of Legionella growth. Examples of disinfectants include mono-chloramine, chlorine, chlorine dioxide, ozone, and ultraviolet light. To reduce the risk of growing and spreading the bacteria, some buildings require a water management program. Certain buildings, such as those taller than 10 stories or housing vulnerable populations, are at an increased risk for Legionella. Building managers and owners can use the CDC’s toolkit to develop a Legionella water management program that works for their building.

Solving problems

Meanwhile, the CDC, along with the Environmental Protection Agency, the United States Geological Survey, and other agencies, works to improve the outlook of water quality in the US with the information and tools at their disposal. While it may seem surprising that more illnesses are reported coming from government-regulated water sources, Dr. Benedict points to differences in reporting and data collection as a probable factor in this difference.

A CDC microbiologist pours water samples from a building experiencing a Legionnaires’ disease outbreak into a filtration system to test for Legionella.( Credit: CDC.)

“We recognize that outbreaks from private wells are difficult to detect in this surveillance system. For example, outbreaks associated with small private wells are probably not captured well and underrepresented.”

Benedict continues, “This report includes data from outbreaks that occurred in 2013 and 2014 and were reported to the National Outbreak Reporting System. These data likely do not capture all of the outbreaks or cases that occurred during this time. Outbreak reporting varies among states, and these data may not present an accurate picture of waterborne disease outbreaks in a given state or type of water system.”

Despite the gaps in reporting, the data we gain from surveillance of waterborne disease outbreaks is invaluable to the public health.

“Outbreak surveillance data play a critical role in waterborne disease prevention for a broad range of germs across many types of water, so we treasure the efforts of states that have contributed reports through the National Outbreak Reporting System,” Dr. Benedict concludes. “Although these data are limited, outbreak surveillance still helps us to understand the cause of water-related illnesses so that threats to safe water can be addressed. For example, EPA has used data from this system in the past to develop regulations around drinking water. Water treatment and disinfection has helped ensure access to healthy and safe water for nearly all Americans. Providing safe drinking water was one of the most important public health achievements of the 20th century.”

Top image: Legionella pneumophila, a bacterium that can cause Legionnaires’ disease, growing on specialized microbiological media (BCYE). (Credit: CDC.)

0 comments