Research collaborative deploys glider lineup for hurricane season

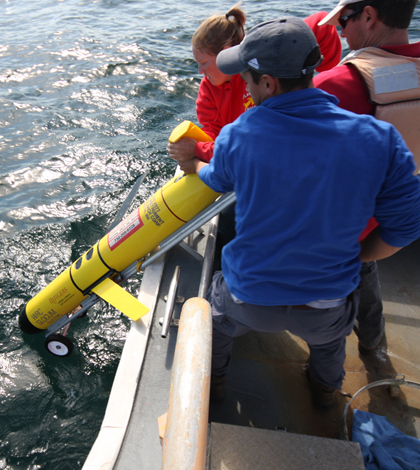

A Rutgers crew deploys a glider in the Atlantic Ocean (Credit: Rutgers University)

Any hurricane heading toward the East Coast in the next month will face a picket line of gliders waiting to collect data on the whipping winds and turbulent sea.

A total of 11 research organizations are deploying the unmanned gliders from Nova Scotia to Georgia to collect data on the intensity of hurricanes to improve modeling.

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Integrated Ocean Observing System is coordinating the effort. If all goes to plan, 13 to 16 gliders will be stationed along the East Coast in what could be the largest organized deployment of gliders in history.

“In this particular case, everybody is actually talking with each other, so that when they are putting the gliders out there they are optimizing their positions,” said Zdenka Willis, director of the Integrated Ocean Observing System.

The gliders in this deployment are all maneuvered by changes in buoyancy and current movements. Willis said researchers will be watching weather forecasts to point gliders toward the path of storms up to a week in advance.

Data collected during the deployment will be handled by IOOS and saved in the NOAA National Data Buoy Center. It will then be distributed to the National Weather Service and to climate modelers. IOOS also hosts an interactive map of the glider’s locations.

This will mark the third year in a row gliders have been deployed on the East Coast during hurricane season. For the past two years, gliders that were already deployed remained at sea during hurricanes Irene and Sandy.

Willis said glider data recorded during Hurricane Irene revealed that forecasters missed information and overestimated the hurricane’s intensity. “Basically what they found was that the models used for hurricane intensity hadn’t actually predicted that the ocean had cooled,” she said.

Predictions for Hurricane Sandy were much closer to glider data. Willis said that the two trials were still limited in their scopes. The only absolute determination that came from the deployments was that more gliders need to be deployed in more hurricanes.

September’s glider deployment may be the largest in history if every organization deploys gliders as planned. Gliders will be deployed by the University of Delaware, Rutgers University, the Office of Naval Research, Dalhousie University, University of Maine, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, University of Massachusetts, Virginia Institute of Marine Sciences, Skidaway Institute of Oceanography, North Carolina State University and Teledyne Webb.

A Rutgers glider heading out out for deployment (Credit: Rutgers University)

All the gliders are Slocum Gliders, built by Teledyne Webb. Willis said organizations did not plan on this. She said it could be due the gliders’ proven performance in shallower waters of the East Coast’s continental shelf. Teledyne Webb also won the Navy’s competition for operational use of gliders and National Science Foundation competition for gliders in support of the Ocean Observatories Initiative.

Slocum Gliders maneuver through the water by varying their buoyancy. They move up and down in a zigzag pattern, which allows them to travel horizontally as they ascend and descend on forward angles.

The autonomous underwater vehicles on this deployment will serve double duty. While they wait for a hurricanes or tropical storms to head toward the East Coast, the gliders will collect data related to other facets of their home organization’s research.

All the gliders have conductivity, temperature and depth sensors onboard. Some will be tracking the movements of tagged fish. Others are equipped with optical sensors to track algal blooms and other water quality parameters. Many also are equipped with acoustic Doppler current profilers to track water movement.

Unfortunately, there’s always the possibility of failure during deployment. Several software fail safes are in place which can trigger an air bladder inside the glider causing it to float on the ocean’s surface.

Previous deployment during Hurricane Irene proved the perils a glider can face. One of the Rutgers gliders deployed during that mission turned into a drifter after it lost a wing. “When it lost that wing it popped back up to the surface and bobbed out there in the bad weather,” Willis said.

A fisherman and his son picked the glider up a few days later.

The risk is worth it. Willis said the relatively fast development of gliders have changed the way researchers can measure the ocean. “It’s really critical because we’ve never been able to have a cost effective way to measure the three dimensional ocean,” she said.

0 comments