Running RECON with the Sanibel-Captiva Conservation Foundation

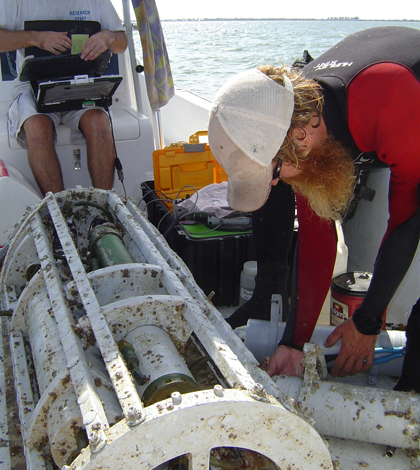

Scientists perform monthly service updates on a LOBO sensor package (Credit: SCCF)

In January 2010, a cold snap swept through Florida, bringing air and water temperatures down well below normal with disastrous effects for some marine species.

A die-off of snook, a popular game fish, was so widespread that the state closed the recreational harvest for the species–a ban that remains in place today.

The chill was also hard on sea turtles, which suffer from “cold-stunning” when water temperatures drop below a certain threshold, according to A.J. Martignette, a research assistant with the Sanibel-Captiva Conservation Foundation Marine Laboratory.

“They get very lethargic and can have trouble coming to the surface to breathe,” Martignette said.

The conservation foundation laboratory’s seven-station water quality monitoring network in the waters around Sanibel and Captiva islands, Gulf Coast barrier islands in Southwest Florida, recorded water temperatures in the mid- to low-40s Fahrenheit. Prior to that, the lowest temperature the system had recorded since its installation in 2007 and 2008 was around 55 degrees.

“We were diving in water that got down to 43 degrees,” Martignette said. “That was very cold for here.”

The River Estuary Coastal Observing Network, or RECON, measures a full array of water quality parameters at seven locations around Sanibel Island and up the Caloosahatchee River. Continuous measurements from a Satlantic LOBO instrument at each site are broadcast in real-time to the network’s website.

Today, the network is programmed to alert managers via email if temperatures persistently hover around levels that could trigger another cold-stunning event. The early warning could help save time in rallying troops to help scoop up struggling turtles and take them to rehabilitation centers.

“There are state resources that can be mobilized,” said Eric Milbrandt, the marine laboratory’s director. “Universities and research labs that may have vessels can put them on alert and maybe sidetrack some of their other activities to come and rescue animals.”

RECON includes seven sites monitored continuously by Satlantic LOBO sensor packages (Credit: SCCF)

The real-time data from the network also helps inform the foundation’s weekly consultations with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers over water management in the area. Sanibel Island sits at the mouth of the Caloosahatchee River, which flows from Lake Okeechobee and along the northern edge of the Everglades before draining into the gulf. The corps operates a dam on the river that controls how much water flows into the estuary. The volume of that flow has a big influence on the nutrients and salinity in the marine habitats around the island, but the corps also has to meet needs for flood control and water storage for Everglades sugar cane farms.

“The fresh water that’s coming from that structure is highly managed and manipulated depending on the needs of the people around Lake Okeechobee, the needs of the Everglades and the needs of the Everglades agricultural area,” Milbrandt said.

Releases from the dam are typically low in the winter because the corps is storing water for agriculture. The drop in freshwater inputs drives salinity up around Sanibel Island. In the summer, dam releases are increased to help control flooding, which pushes salinity down.

“And that stops any submerged aquatic vegetation from being able to get a foothold in there,” Marginette said. “The freshwater grasses die off in the winter when the salinity goes up. And then the saltwater grasses in die off in the summer when the salinity goes down.”

Data from the Sanibel-Captiva Conservation Foundation’s RECON helps advise water managers in the area (Credit: SCCF)

The flood control releases also bring high nitrogen and phosphorus loading, which is thought to intensify red tide blooms.

So the Sanibel-Captiva Conservation Foundation joins a weekly conference call of scientists and generally requests that the corps sends more or less water, depending on the time of year. Fresh data from RECON helps back up their arguments.

“That’s where the real-time capability comes in very handy,” Martignette said. “If we were getting the data two weeks after the fact, it wouldn’t do us much good for that.”

RECON also includes several weather stations that help inform the local boating community. Boaters will also benefit from a planned expansion of the network of. A Nortek AWAC sensor paired with NexSens CB-500 Coastal Data Buoy will bring real-time wave and ocean current readings to the area for the first time, Martignette said.

“We have the scientific reasons for it,” he said. “But the website is there for anyone to go on and check out.”

Top image: Scientists with the Sanibel-Captiva Conservation Foundation perform monthly service updates on a LOBO sensor package (Credit: SCCF)

0 comments