Researchers sort out Saharan dust’s surprising effects on Houston air quality

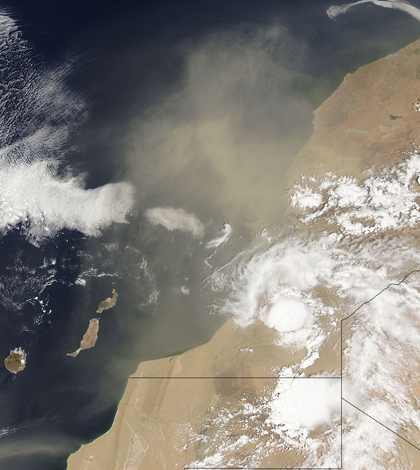

A plume of Saharan dust blows over the Atlantic Ocean from North Africa (Credit: NASA)

The petroleum refineries and other industries concentrated around Houston give air quality regulators there plenty of local pollution sources keep track of. Meanwhile, scientists are helping them keep closer eye on a surprising, far-flung source of particulate matter: dust from the Saharan Desert.

It’s not news that the dust from arid North Africa escapes into the atmosphere and is redistributed hundreds to thousands of miles away, but research on the phenomenon has focused mostly in its influence on geology and climate.

The effects of Saharan dust on urban air quality in other continents has been less understood until recently. One reason for the increased attention in Texas is a 2012 tightening of federal air quality standards that reduced the acceptable concentrations of airborne particulate matter. If states violating the standard can show that some portion of the pollution came from sources outside of their regulatory control, it won’t count against them.

The stricter rules make parsing the sources of pollution and their relative contributions all the more important, according Shankar Chellam, professor of civil and environmental engineering at the University of Houston.

“Now the state is investing and is interested to know essentially all the sources,” Chellam said. “Every speck of dust, they want to know where it came from.”

Chellam and his colleagues have developed a method that not only detects Saharan dust in local air samples but also quantifies its contribution to total particulate matter levels. The results of their first attempt were recently published in the journal Environmental Science and Technology.

A plume of Saharan dust blows over the Atlantic Ocean from North Africa (Credit: NASA)

Their method should improve upon past efforts, which have mostly relied on satellite images of airborne plumes crossing the Atlantic. The problem with that approach, is that it doesn’t quantify the amount of dust in the areas that matter most. The images are limited to identifying dust high in the atmosphere and can only say whether the dust was present, not how much is there.

“That’s where we come in, because our measurements are at ground level,” Chellam said. “We sample the air that people actually breathe, not just the air that is 2 to 6 kilometers from the earth’s surface.”

Chellam came into Saharan dust research mostly by accident. His past research focused on identifying the chemical signatures for specific sources of air pollution like petroleum refineries and motor vehicles. By collecting samples and analyzing the levels of around 40 metals, he and his collaborators can develop an elemental profile for each source.

Shankar Chellam and Steve Paciotti, Texas Commission on Environmental quality set up particulate matter samplers

While collecting data on Houston’s industrial pollution sources in 2008, they found certain days showed increased levels of particulate that couldn’t be tied to any industrial sources. Their chemical analysis of the particles from those days seemed to signal it was from a natural source. They turned to satellite imagery and found a plume of Saharan dust had indeed made its way to Houston.

“Our sampling that was done in Houston was not at all based on the Saharan dust,” Chellam said. “It was an accidental discovery that this impacts Houston at this great extent.”

Once the researchers knew they were dealing with Saharan dust, they turned to an air sampling station on Barbados maintained by Joseph Prospero, emeritus professor of marine and atmospheric chemistry at the University of Miami. Prospero has used the station there to study the geologic and climatic effects of Saharan dust. It was an ideal place for Chellam’s group to gather a sample that had crossed the Atlantic but hadn’t yet mixed with the industrial and natural dust of the continental United States.

Data from the Suomi NPP satellite shoes concentrations of aerosol particles on July 31 to Aug. 2 this year (Credit: NASA)

The researchers then developed and elemental fingerprint for the Saharan dust and plugged it into a model along with the signatures for refineries and other local sources. The results show that, for three days in July, sand transported to Houston from North Africa made up more than half of the particulate matter pollution at the sampling sites.

So far the researchers have only applied their method to the samples from the 2008 Saharan dust event, though the results were consistent over sampling sites locations in Houston and two categories of particulate matter. Chellam said their next step is to secure funding to analyze more events and prove that the method is robust and can be applied universally.

“I believe that our method can separate the various sources carefully,” he said. “We can provide that information to the regulator, and they can do what they need to do.”

Image: A plume of Saharan dust blows over the Atlantic Ocean from North Africa (Credit: NASA)

0 comments