Scientists look under Lake Superior ice to further Great Lakes research

A crew deploys the under-ice observatory in the Portage Waterway (Credit: Guy Meadows)

In the throes of winter, researchers on Lake Superior find it hard to collect data. The buoys they rely on during the summer months are largely useless when the lake freezes over. Going through the ice to set up winter monitoring stations isn’t always possible, they’ve found.

“When all the gliders (unmanned aquatic vehicles) and buoys are put away, we’re scientifically blind,” said Guy Meadows, director of Michigan Technological University’s Great Lakes Research Center

In an attempt to get below the ice and study what goes on there, scientists at the research center have built a small-scale underwater observatory and deployed it under a dock on the Portage Waterway. Researchers installed the rig before the lake iced over to learn what difficulties they may face when larger underwater observatories are operating in the lake during winter.

The small observatory was constructed using instruments the research center had on hand and provides information on water quality and currents. It has an aluminum, pyramid-shaped base supporting a YSI 6600 water quality sonde and Nortek acoustic doppler current profiler. An integrated webcam let scientists see what happened beneath the ice during the recent winter’s deep freeze.

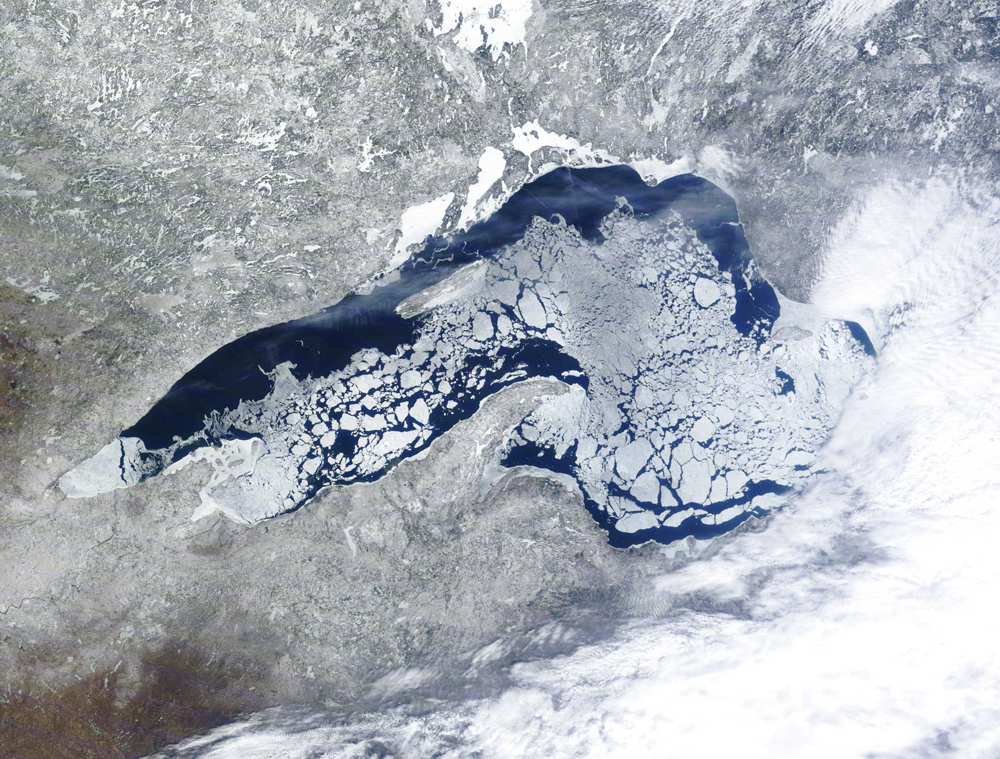

Ice on Lake Superior on April 20, 2014 (Credit: NOAA GLERL/Space Science and Engineering Center, University of Wisconsin-Madison)

Meadows says the camera captured the complexities of light penetration through the ice, something that affects underwater photosynthesis and dissolved oxygen levels. After major storms that dumped several feet of snow on the icy lake, the bottom of Lake Superior would be very dark, he says.

His team also found that sunlight levels below water tend to lag behind those above by about an hour. So on a clear day, light reaches the bottom of Lake Superior around an hour after sunrise.

“We’re very much interested in the effects that low light has on underwater photosynthesis,” Meadows said. “And we know very little about those processes during the Great Lakes winter.”

A series of photos of a mudpuppy captured by the observatory’s camera (Credit: Guy Meadows)

All data from the observatory were transmitted to the research center via a communications cable and then shared on the Upper Great Lakes Observing System website, where they are available for download. With the lake still icy, data will be collected until the observatory can be pulled out.

Meadows looks to work with researchers from other institutions to install similar underwater stations in Lake Superior. The Great Lakes Research Center is also applying for funding from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration to install larger-scale cabled observatories akin to those used in the world’s oceans to monitor the lake in winter. Canada’s University of Windsor is spearheading an effort to install them near the Canadian shore.

0 comments