Six-year study tackles nonpoint source pollution in Louisiana watershed

An intensive 6-year water quality study of an agricultural watershed in Louisiana should give managers there a leg up in tackling nonpoint source pollution along the Bayou Plaquemine Brule.

Land-use in the bayou’s watershed is 89 percent agricultural, producing rice, soybeans, sugarcane and crawfish. Degradation from the runoff landed the slow-moving river on the state’s list of impaired waters in 1998.

In an effort to better understand water quality issues in the basin, Durga Poudel led a comprehensive data collection campaign throughout the watershed from 2002 to 2008. Poudel, professor and assistant director of the School of Geosciences at the University of Louisiana at Lafayette, said he went into the study hoping to answer the questions facing managers in any impaired watershed.

“The questions we had were very general,” he said. “How does the water quality differ from season to season, and what determines this variability? And what are the hottest spots in the watershed so that a watershed management plan could be developed in order to control nonpoint source pollution?”

The results of the study, published in June in the Journal of Soil and Water Conservation, are derived from a 900-plus-point dataset built on site visits to seven monitoring stations every fifteen days from March 2002 to February 2008.

At each site, Durga or one of his collaborators lowered a YSI 6820 sonde from a bridge to measure dissolved oxygen, temperature, turbidity, conductivity and pH at three depths in the stream. They also collected water samples for laboratory analysis of biological oxygen demand, total suspended solids, soluble reactive phosphate, total phosphorous, nitrate, nitrite and total nitrogen.

“For six years, doing this field work and maintaining everything was quite a big challenge in a way,” he said. “But it went very smoothly. We generated tons of data.”

One of the things that Poudel hoped to find in that data was a strong correlation between some of the parameters they were measuring. If the data showed a strong link, he said, that could save future monitoring efforts the expense of covering the full array of, say, different types of specific nutrients.

Their analysis showed that monitoring programs that include total nitrogen or total phosphorous don’t necessarily need to also cover nitrate, nitrate or phosphate.

“We can reduce a number of parameters strategically, which will reduce the laboratory cost,” he said.

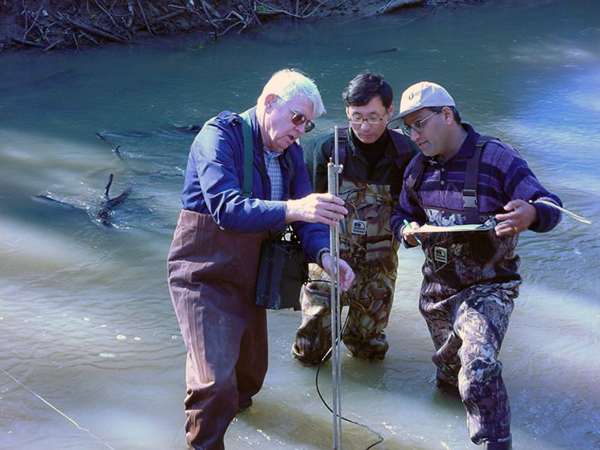

Durga Poudel, right, led the nonpoint source pollution study on the Bayou Plaquemine Brule

Another goal was to determine which dimensions of nonpoint source pollution were having the biggest impact on the bayou’s dissolved oxygen levels. Poudel said the conventional wisdom has been that it’s mainly surface water temperature that drives dissolved oxygen down, and some agricultural scientists suggest nutrients are more to blame. But his study found otherwise.

“The factor analysis of this huge dataset clearly showed sediment is the main culprit, followed by nutrients and then temperature,” he said. “That’s a priority now for management. Once you control soil erosion, you minimize the sediment loss, and that improves the water quality.”

Finally, Poudel and his colleagues sought to find the areas of the watershed that posed the greatest concern for non-point pollution. To find this out, they applied the data to the Soil and Water Assessment Tool, a basin-scale model supported by the U.S. Department of Agriculture for determining land-use effects on water bodies.

Though the pollutant concentrations tended to be higher in the upper reaches of the watershed, the results of the modeling helped make it clear that the “hot spots” for sediment and nutrient loading are in the lower reaches.

“Since the concentrations are lower in the lower reaches, that leads people to think the critical areas for nonpoint source pollution are in the upper reaches where concentrations are high,” Poudel said. “That’s not the case, because the concentration and the load are two different things.”

Poudel said this sort of comprehensive research is necessary to help water and land managers develop sound plans to restore water quality in impaired watersheds like the Bayou Plaquemine Brule.

“It is really important to generate high-quality, consistent data in order to be able to make conclusions confidently so that the findings can be translated into management plans which will enhance the water quality,” Poudel said. “That’s the utility of this research after so many years of hard work.”

0 comments