Researchers trace dye through a Florida treatment wetland

Crews apply Rhodamine dye to Florida treatment to study flow problems (Credit: Wetland Solutions, Inc)

Water management agencies are increasingly introducing engineered wetlands into treatment schemes to slow down runoff and remove nutrients and sediment. These natural filters can be cost-efficient and bring added bonuses like wildlife habitat, but they require different design and management approaches than traditional treatment systems.

“You’re working with erodible soil and vegetation that grows in at different spatial densities and other aspects that you can’t engineer as well as you can a concrete tank,” said Chris Keller, a project manager and environmental engineer with Wetland Solutions, Inc., a Florida-based consulting firm that specializes in treatment wetlands.

Those kinds of complications are among the reasons that Keller and Wetland Solutions were called upon by the St. Johns River Water Management District to assess a treatment wetland in an agricultural area in Northeast Florida. The consultants turned to a tracer dye study to characterize the way water flowed through the system and identify areas where the flow was short circuiting the wetland and missing out on the treatment processes.

The district constructed two treatment wetlands in the mid-2000s to filter the nitrogen, phosphorus and suspended sediments that flow off of the region’s potato and cabbage fields. One of those, known as the Deep Creek West Regional Stormwater Treatment Area, is made up a of a 15-acre detention pond that drains into a 38-acre treatment wetland within the Deep Creek Conservation Area. Monitoring of the water flowing through the wetland showed that during certain times of the year the system wasn’t removing nutrients as well as it could be.

“Their data were showing that there were times when they were exporting rather than removing nutrients,” Keller said. “So that was their first clue that something wasn’t right.” Other clues included upland vegetation throughout areas of the wetland, suggesting that some sections were remaining dry and not contributing to the treatment process.

Keller measured Rhodamine concentrations with a Turner Designs Cyclops-7 Rhodamine-WT sensor (Credit: Wetland Solutions, Inc)

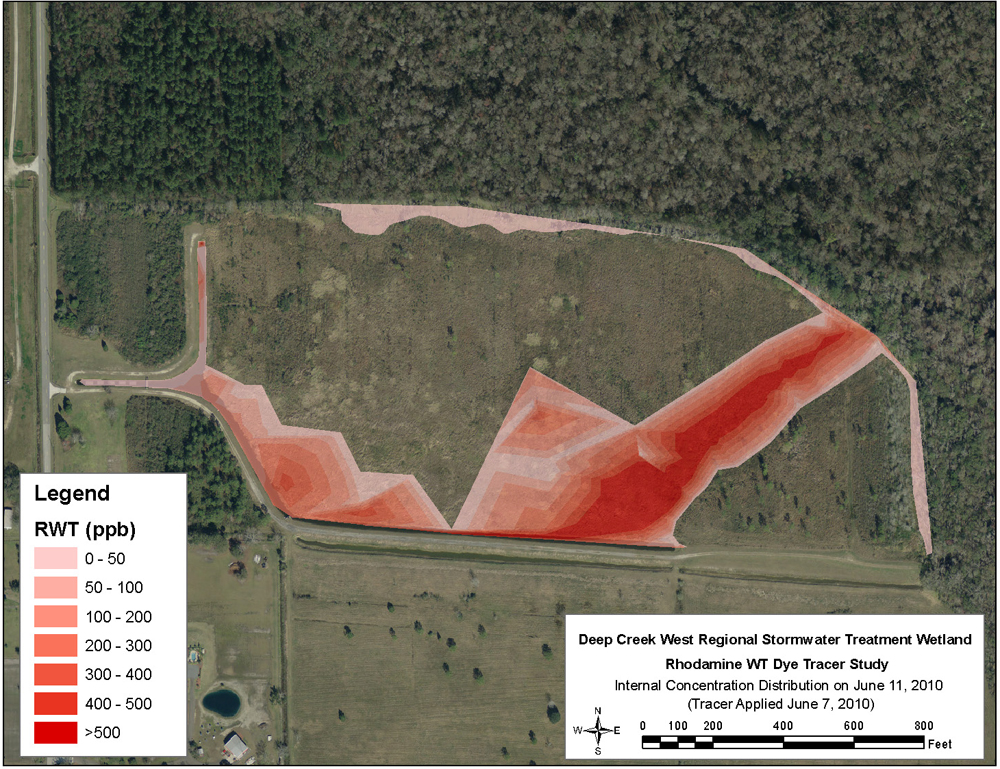

The likelihood was that the topography was allowing the water to take a shortcut through the system, reducing the amount of time the water was exposed to the wetland’s nutrient-removal capacity. In 2010, Keller led a tracer dye study, releasing controlled amounts of bright-pink Rhodamine-WT into the wetland’s inlet and measuring the dye concentrations with a Turner Designs Cyclops-7 Rhodamine-WT sensor. Dye concentrations were periodically measured in transects across the wetland, as well as continuously by a sensor installed at the system’s outflow.

Keller set out to map the flow through the wetland with a Rhodamine sensor and a GPS unit hooked to a Turner Designs DataBank data logger. By walking several transects across the wetland and taking paired dye concentration and location readings roughly every 25 feet, he produced data to create maps of concentration gradients that show the route that water was taking through the system.

The dye concentration data helped define the channel where water flowed through the wetland (Credit: Wetland Solutions, Inc)

The dye sensors came in most useful at the wetland’s outfall, where an instrument logged concentration data continuously for a month after the Rhodamine was added. That information allowed the engineers to calculate how much time it takes water to move from the inlet to the outlet. Based on that and other data, they could make quantified projections about the effects of potential modifications to the wetland–such as grading to flatten high ground or digging trenches to improve the distribution of water.

“The tracer study did provide solid, irrefutable documentation that there were indeed preferential flow paths in the wetland,” Keller said. “That gives you a baseline from which you can estimate what corrections to those problems might do.”

Top image: A crew apply Rhodamine dye to Florida treatment to study flow problems (Credit: Wetland Solutions, Inc)

0 comments