American Lakes are Getting Murkier

Walden Pond, now a popular swimming hole, is becoming murkier. (Credit: Andrew Douglass [CC BY-SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], from Wikimedia Commons)

Limnologist Dina Leech found herself reading more and more about lakes turning green, filling up with algae, and browning. She found herself wondering, could lakes be getting murkier more generally? Dina and her team decided to use data from the National Lakes Assessment (NLA) program directed by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) to find out, and the recent study was born.

Dr. Dina Leech spoke to EM about the study, and about why lakes appear to be getting murkier.

A massive data set on American lakes

“Every five years they go out with hundreds of volunteers and sample over a thousand lakes across the country,” explains Dr. Leech. “And at each one of these lakes, they take measurements on the chemistry, they look at what kind of algae is growing in the lake and how much, what kind of zooplankton are there and how many. They measure things like how deep it is, how big is the lake, and what’s going on in the watershed around the lake.”

The first such assessment happened in 2007, and the second took place in 2012. Dr. Leech confirms that an assessment also took place in 2017, but it has not yet been processed; that data probably won’t be publicly available until 2019 or 2020, so it isn’t included in their study.

Taking this many samples in so many places is a massive undertaking.

Dr. Dina Leech. (Credit: Longwood University, http://www.longwood.edu/directory/profile/leechdmlongwoodedu/)

“They actually use an algorithm that is based off a database kept by the United States Geological Survey (USGS) of all the lakes across the country,” details Dr. Leech. “It includes not only where they’re located but also their size, depth, and surface area. The lakes are selected from this database for every five-year cycle using a stratified randomized design. So they’re randomly selected, but they’re stratified within size groups so that each lake that’s picked is very similar to several other lakes within that particular size class. That’s why even though only 1,000 lakes are measured we’re actually able to project what we saw in those 1,000 lakes to tens of thousands of lakes across the US.”

This is strikingly different methodologically than the way many scientists come to study lakes.

“Often, limnologists are like, ‘hey, this lake is close to my university, I’m going to start sampling it,’” remarks Dr. Leech. “That’s great, but that lake is not always representative of other lakes that could be in your region. The power of the National Lakes Assessment is that the lakes are not always picked based on accessibility. They’re selected more on being representative of several other lakes within the region.”

This highlights an interesting difference in the literature. There are, largely, two kinds of data on lakes available: repeated sampling of specific lakes over time, and this larger survey with many lakes sampled, but only once during the summer in a sampling period.

“There is value to both of them,” offers Dr. Leech. “You can’t have all of them sampled all the time, it would be awesome, but it’s just logistically and financially impossible. That is one of the points that are important to highlight about our results, we’re basing these trends on two-time points, one in 2007 and one in 2012. So we get a lot spatially but there’s not a lot of temporal data there.”

Lake Tahoe, a classic blue lake. (Credit: By Michael – originally posted to Flickr as Emerald Bay, CC BY 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=8994280)

Furthermore, some lakes were actually sampled twice.

“Out of the 1,000 plus lakes that were sampled, 401 lakes were sampled in both time periods,” comments Dr. Leech. “So we were able to look at those lakes and see how did these lakes change between the five year period. And they showed a similar trend.”

Murkier and murkier

“When we looked at the whole data set in 2007, we found that blue lakes are low in nutrients and organic matter, and they were the most common lake type,” states Dr. Leech. “About 45 percent of the lakes in the 2007 dataset were categorized as blue.”

These lakes had low total phosphorus values, and their organic matter was measured based on something called true color. To assess true lake color, the researchers filter the water sample to remove all the particulates, leaving only the dissolved components, and then evaluate color.

“So if there’s organic matter in there then it should become browner in color after removing particulates, that’s browning,” explains Dr. Leech. “Most of the time people just classify lakes based on their total phosphorus concentration because they’re thinking mostly about algae. But now we know that organic matter is also coming off the land into our nearby waters, so we use both total phosphorus concentration and true color values, with true color being a measure of organic matter load.”

In 2007, most lakes evaluated were blue: low and phosphorus and low in color. However, the 2012 dataset was surprising for the team.

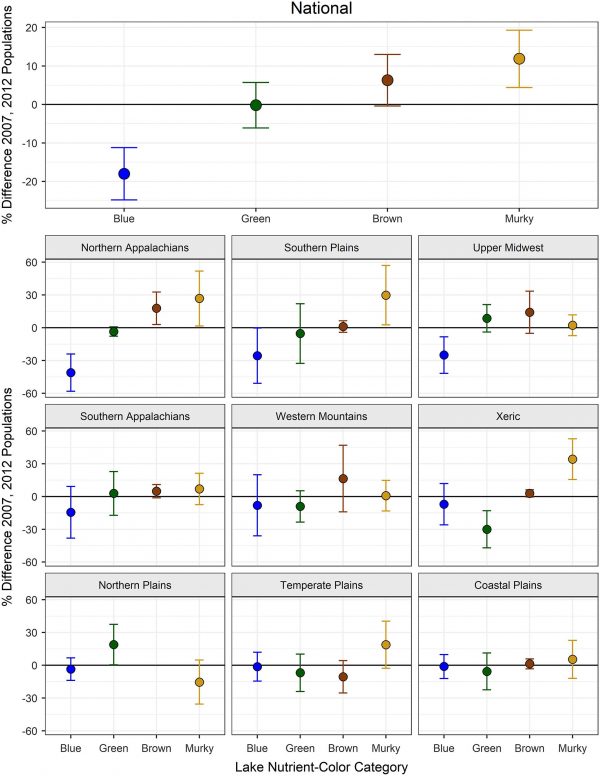

“When we looked at the data set in 2012, murky lakes become the dominant lake type,” remarks Dr. Leech. “Blue lakes went from about 45 percent in 2007 to 28 percent of American lakes in 2012—a massive jump in a short period of time. Murky lakes, lakes that are high in both total phosphorus and organic matter, increased from 23 percent in 2007 to 35 percent in 2012.”

The team also analyzed how much algae was in the different kinds of lakes, blue, green, brown and murky.

“There’s even more algal growth in murky lakes compared to green lakes, and most of that algae was cyanobacteria, which we know can be potentially harmful to humans and other organisms,” Dr. Leech describes. So that was a surprise.”

Graph depicting change in lake color from 2007 to 2012. (Credit: Leech et al., https://aslopubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/lno.10967)

The team also discovered a sign of problems to come in the food webs supported by these lakes.

“We looked at the ratio of zooplankton to algae because that number can give you an indication about energy moving up the food chain,” explains Dr. Leech. “We found that number was lower than what we’d expect. This suggests that not a lot of energy is moving up the food web, so we may see problems with fisheries within these murky systems, where there may not be enough energy moving from the base of the food web to the top, to the higher trophic levels to support those big fish.”

This suggests that water quality is still an issue around the country, but it also indicates that we need to generate more innovative solutions for runoff problems. While nutrient runoff is usually the focus for policymakers, organic matter runoff and how or why it is increasing also demands attention.

For now, researchers like Dr. Leech are working to make the best use of huge data sets like that produced by the NLA.

“There are more and more scientists starting to use the data,” comments Dr. Leech. “We were just at the meeting of the Association for the Sciences of Limnology and Oceanography (ASLO), and it was kind of fun to see how many more people are using the database in many different ways. I think more people are looking to big data to answer these really big questions, like are the lakes in our nation changing? And if so, how?”

Even some of the country’s most iconic waterways are getting murkier—Walden Pond, for example.

“Walden Pond is naturally brown, like many of the lakes in Massachusetts and New England, where there are a lot of wetlands, and they’re receiving that organic matter from the surrounding land,” adds Dr. Leech. “But I read recently that Walden Pond is the local swimming hole, and now they’re having issues with algae, so they’re like telling people not to pee in the pond. But that’s another good point: lakes can naturally exist in any one of these states. But it’s the fact that they’re shifting so fast that is concerning, and we’re finding murky lakes where we wouldn’t necessarily.”

Top image: Walden Pond, now a popular swimming hole, is becoming murkier. (Credit: Andrew Douglass [CC BY-SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], from Wikimedia Commons)

0 comments