Anguish of the Amazon: Climate Tipping Points and the Loss of Rainforest Resilience

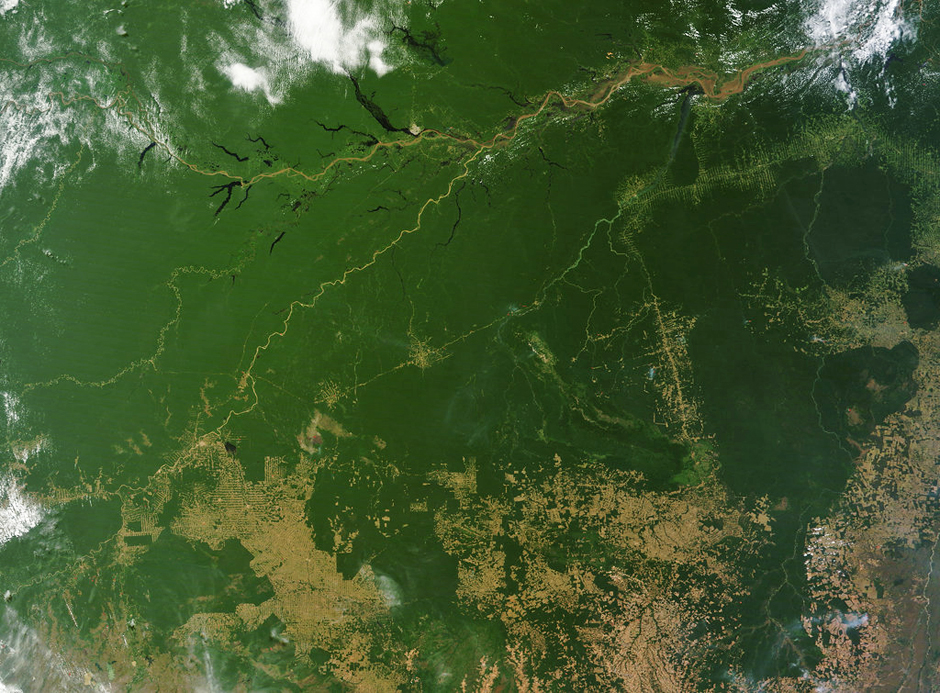

In the south, extensive land-cover change can be seen where forest is being harvested and turned into agricultural land, typically soybean or cattle pasture. Here the green forest gives way to tan land, often with remnant stripes of green marking small stands of timber yet to be cut. Ultimately, the deforestation in these areas will be complete. In some areas, red hotspots mark fires, typically used to burn debris and stumps. (Credit: NASA)

In the south, extensive land-cover change can be seen where forest is being harvested and turned into agricultural land, typically soybean or cattle pasture. Here the green forest gives way to tan land, often with remnant stripes of green marking small stands of timber yet to be cut. Ultimately, the deforestation in these areas will be complete. In some areas, red hotspots mark fires, typically used to burn debris and stumps. (Credit: NASA)When considering the health of sensitive environments such as the Amazon rainforest, Chris Boulton, Research Fellow at the Global Systems Institute at the University of Exeter, emphasizes that appearances can be deceiving. “I became interested in the research because of the idea of climate tipping points. In other words, a system under duress, like the Amazon rainforest, can seem fine, but it can undergo rapid decline in a short period of time.”

The research Boulton and his colleagues are doing involves finding the characteristics that show a movement towards a climate tipping point and then hopefully ameliorating or stopping that movement before it is too late and the tipping point for the system has already passed. “Our goal is to quantify the movement towards a climate tipping point, measured as a loss of resilience in the system. Resilience is essentially how quickly a system recovers from perturbations, in this case droughts for example.” says Boulton.

The Amazonian Climate Tipping Point

The data Boulton and colleagues used to measure changes in Amazon resilience came from satellite images. Vegetation Optical Depth (VOD) was used to estimate monthly vegetation water content, while Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI), a different vegetation index measuring the greenness of the plants, was used for comparison. Great care must be taken in interpreting the images, as an increase in greenness does not necessarily mean the forest has recovered. Sometimes green, i.e., photosynthetic activity, does not indicate a healthy forest but instead suggests that there has been grass growth in its place.

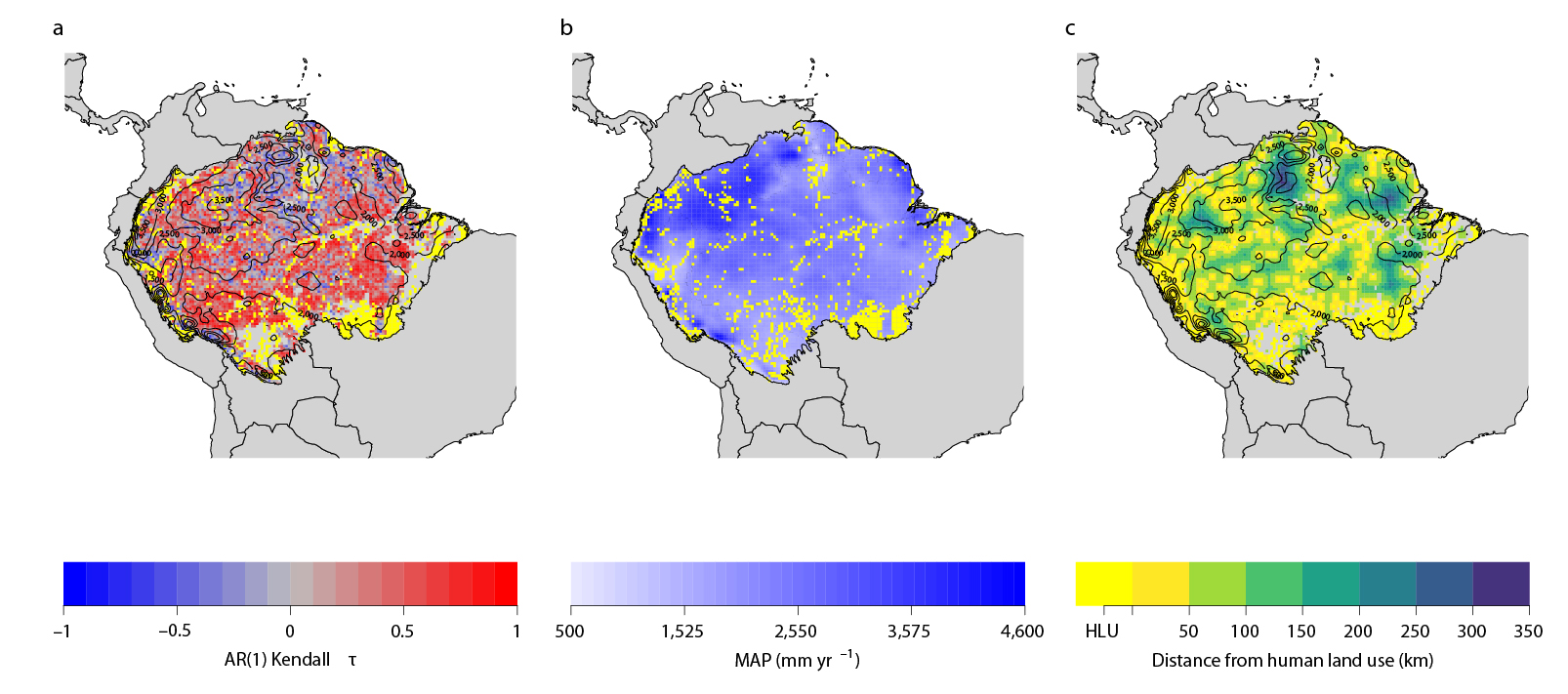

As far as what exactly in the images translated into a meaningful loss of resilience, Boulton said that each pixel or location has a VOD or NDVI value each month, from which a time series can be created and analyzed. The team measured ‘lag 1 autocorrelation’ or AR(1), a correlation between values that are one month apart. “Measuring this AR(1) over time and seeing an increase in it suggests that the system is becoming more sluggish in its response to perturbations and, as such, losing resilience,” says Boulton.

Although the Amazon still appears to recover when exposed to dramatic changes in rainfall and/or temperature, it takes longer to return to equilibrium. “In the last 20 years, we have been seeing more droughts, and we have seen that the Amazon is restoring itself more slowly than it used to,” says Boulton.

VOD AR(1) Kendall τ values. b, MAP from the CHIRPS dataset from 1991 to 2016. c, Distance from human land use (HLU) (Methods). In a–c, MAP contours are shown, along with HLU grid cells (yellow). (Credit: Springer)

Threats to Vegetative Biodiversity

While Boulton and his team did not investigate whether certain tree species in the Amazon are being affected by logging, drought, fire, and other stressors more than other species, they did investigate the forest makeup and compared it to terrain primarily covered by grasses. Boulton’s study only looked at pixels that had more than 80% broad leaf cover. “Our impression is drought-resilient plants may start taking over, but this depends on how fast the resilience is being lost and whether or not the forest can ‘keep up,’” says Boulton.

Looking at the satellite data from 2005 and 2010, researchers previously found that the NDVI sprung back faster than in some other years, but they were disappointed to find that the green growth was primarily grasses, not trees. “Trees react more slowly,” notes Boulton. “During heat waves, grasses may die faster but they also come back faster than trees.”

Boulton and his team aren’t the only ones who are tracking changes in the Amazon with growing alarm. While it is important to document the changes and try to understand them, studying them at this point may seem like an exercise in futility. However, Boulton believes that, despite the unrelenting stresses on the Amazon, people can do more than merely chronicle its demise.

“Studying the individual areas and their changes over time, we’ve found that it’s the urban areas and fields that are losing resilience faster,” he says. “These are also the areas where people interfere with natural processes the most, where biodiversity is being threatened. These areas are where trees are being cut down, where evapotranspiration processes are getting altered because of the trees being eliminated. Fires are also affecting these areas severely.”

Gramado, Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil (Credit: Renan Bomtempo via Pexels)

Amazon Logging

Boulton and his team are looking at local, regional, and global actions that could possibly be performed and would help the Amazon, even now. “We’re seeing that the Amazon forest is not taking in as much carbon as it was in the past. This is because trees are being cut down, so there aren’t enough trees to contribute to the carbon sink.” Meanwhile, the drier climate means fires are more frequent and severe. “Logging heavily contributes to resilience loss in the Amazon,” Boulton emphasizes. “Any reduction in logging would help, even now. It would help restore the carbon sink function and slow down or maybe even stop the loss of diversity.”

In the near future, Boulton hopes to look into machine learning capabilities and how they could assist in detecting an Amazonian climate tipping point. “We want to see if we can detect something different or if the machine learning data can give us a different perspective,” he says. “Ultimately, I’m a mathematician, and I got into climate change because the math interested me. I wanted to do something useful with maths and statistics. This study, and adding the machine learning aspect, would help me accomplish that.”

Boulton adds that, even though doom and gloom pervade social media on the topic of climate change and the Amazon, the situation is not as hopeless as it may seem. “This is an early warning, we still have a chance to do something,” he emphasizes. “So even though you see doom and gloom on social media, it’s positive in a way, because people are paying attention to it, and people haven’t given up yet. It’s not over, we can still change course.”

0 comments