Assessing Cumulative Risk From Water Pollutants

Water droplet on tap. Credit: Ishwah Murthi [CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)]

New research from scientists at the Environmental Working Group (EWG) shows that an approach that assesses cumulative risk from water contaminants could save lives. EWG senior scientist Tasha Stoiber spoke with EM about how the team developed the innovative new approach.

“Our organization has worked extensively on tap water over the years, and an updated version of our tap water database was just released in 2017,” explains Dr. Stoiber. “We’ve been thinking about new ways to analyze that data.”

Right now, the risk from contaminants in water quality is assessed one at a time—but that really doesn’t comport with reality. Cumulative cancer risk has been assessed for hazardous air pollutants, and the team hoped they might apply that framework to drinking water.

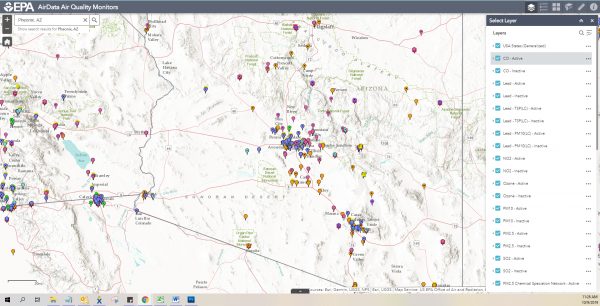

“The EPA’s National Air Toxics Assessment includes a map where you can view air quality and cancer risk,” said Dr. Stoiber. “The cumulative cancer risk is calculated from the sum of the hazardous air pollutants that you might be exposed to in each census tract.”

To apply the framework to drinking water, the team needed to know which carcinogens users were drinking with a high level of granularity.

“We applied this methodology assuming a simple additive cancer risk, similar to what has been done with air toxics,” said Dr. Stoiber. “We wanted to apply a framework beyond looking at one contaminant at a time, and explore how the co-occurrence of multiple carcinogens that we are actually exposed to in real-life scenarios affects health risk. What would the cumulative risk be for each community water system? We started with California data, as a case study, but we could use other state’s datasets and apply the same framework as well. ”

We are able to calculate a cumulative risk the same way we do with cancer risk levels for carcinogens in air.

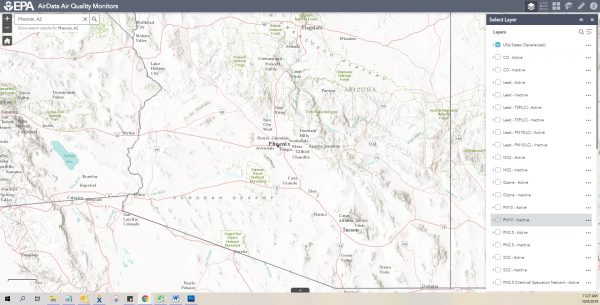

Screenshot of EPA’s air quality map for Phoenix with layers off. (Credit: Author, Thursday, October 10, 2019, https://www.epa.gov/outdoor-air-quality-data/interactive-map-air-quality-monitors)

“We applied one in one million cancer risk levels for carcinogens in the assessment. These risk levels were set by either the California Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment (OEHHA) or by EPA’s integrated risk information system.”

The EPA assumes that when contaminants co-occur in air, risk increases; the EWG argues that this should also apply to water, and they applied this theory in this study.

“There could be other synergistic effects that would actually make the risk greater, or it could be lesser. There’s much more research needed to understand the effects of co-occurring carcinogens. This was our first step in applying a cumulative framework. But with some uncertainty,” adds Dr. Stoiber.

Assessing cumulative cancer risk

From there, the team tried to assess cumulative cancer risk for drinking water systems and presented the two main concepts in their initial research.

“The first is the cumulative cancer risk,” states Dr. Stoiber. “The second, more theoretical concept is a combined metric that looks at the non-cancer health impacts associated with drinking water contaminants. It’s not a quantitative estimate of risk, but a metric used to compare different levels of toxicity of the different drinking water systems.”

Dr. Stoiber acknowledges that there is more research to be done in this area and that the team is merely taking a first step in building on a metric that assesses both cancer and non-cancer related health impacts from cancer-related to multiple drinking water contaminants.

“Part of the problem is that regulated drinking water contaminants can still pose health risks. At the federal level, those regulations are based on the cost of treatment, or a number of different factors, whereas our assessment is health-based. Most of the cancer risk that we calculated is actually below what those federal legal standards would be,” adds Dr. Stoiber.

Indeed, 85 percent of the cancer risk that the team calculated is due to contaminants that are at “allowable legal levels in your water.”

“Our approach is my actual health-based and applies one in a million cancer risk levels,” remarks Dr. Stoiber.

Reducing cumulative risk

We’re all consumers of water, so thinking about drinking water and cumulative risk isn’t easy.

“There’s a number of different things that can be done at a number of different levels to reduce risk,” clarifies Dr. Stoiber. “This is why we assemble all of this tap water data and put it in a usable free tool online so that anyone can look up their specific community water system, and find out what’s in their drinking water. At the consumer level that’s your number one thing to do: research your water, find out what’s in it, and if you can, filter your drinking water, that’s what we recommend.”

The team sees data-gathering tools like theirs as integral to accessing safe water.

Screenshot of EPA’s air quality map for Phoenix with layers applied; the difference is notable, and given this research, it seems like the difference would seem notable in many places. Credit: Author, Thursday, October 10 2019, https://www.epa.gov/outdoor-air-quality-data/interactive-map-air-quality-monitors.

“For example, in California, they passed the human right to water legislation which guarantees every citizen the right to clean, safe, affordable, and accessible water,” states Dr. Stoiber. “A cumulative framework could be another tool to gather data to support those goals, and to help direct resources as needed to the most heavily impacted communities and water systems.”

Filtering is ideal for consumers, but whether or not—or when—utilities and regulators will move toward adopting this kind of cumulative standard is unclear.

“We all know that’s a long way down the road, but the hope is that research like this starts those kinds of conversations,” remarks Dr. Stoiber. “We cannot look at contaminants one at a time, because that, in the past, has been very inefficient and slow. The more that we can look at contaminants as groups, it’s going to improve selection of treatment strategies, and protection of health overall.”

And although it wasn’t a surprise to the EWG team, the results showed that people in smaller communities might be at higher risk from drinking water contaminants.

“A lot of the smaller systems serving smaller communities tended to have more cancer risk,” Dr. Stoiber says. “That wasn’t surprising to us, but it underscores the issue that smaller communities are less likely to have the necessary resources available to be able to tackle these difficult water quality issues. You don’t have the economy of scale when you’re only serving a smaller amount of people. People that live in the most impacted communities in California are well aware of this problem.”

0 comments