Baltimore Checkerspots, Monarchs and Chats: There’s Much to Monitor at Beaver Creek Wetlands

Baltimore Checkerspot Butterfly (Credit: Mike Mushala)

With its orange antennae knobs and distinctive orange, black and white spotted wing patterns, the Baltimore Checkerspot is an unforgettable butterfly. While Baltimore Checkerspots are the state insect of Maryland, they have become rare in some areas of the state where they used to be booming. These declines have happened for a number of reasons, such as loss of wetland habitat due to development and climate change. This is true for Baltimore Checkerspots that live in Ohio, too. Ohio has lost about 90% of its native wetlands, primarily due to drainage to create farmland. These wetlands were once considered “wasteland.” Incredibly, there is still a place in Ohio where the Baltimore Checkerspot is still thriving: Siebenthaler Fen, one of the areas that is part of the Beaver Creek Wetlands.

“People come here every year to see the Baltimore Checkerspots,” says Jim Amon, Vice President of Beaver Creek Wetlands Association (BCWA). Amon is also a retired Professor Emeritus, Biology, Wright State University. “Visitors who come out here on our boardwalk in the Siebenthaler Fen during the four weeks around Memorial Day usually see several. After that, they can still see the orange and black caterpillars. The caterpillars overwinter and then form chrysalises in the spring, which then become butterflies. The Baltimore Checkerspot is a unique and memorable butterfly, well worth a visit.” Visitors can also see another butterfly that has seen declines, the Monarch, and many birds that aren’t easy to find in the rest of Ohio, including the Yellow-breasted Chat and the Sora Rail. “Throughout the spring, summer and fall dragonflies and damselflies put on a spectacular show. Beavers and river otters occupy the stream,” Amon adds. The entire corridor is an important stopover place for migrating neotropical birds. During spring migration, it is common to find about a hundred or more species in the BCW.

“Beaver Creek Wetlands are groundwater driven and are mostly fens. Fens are unique in that they are the home to many rare species. Baltimore Checkerspots and other similar butterflies need the fen environment to thrive. Fens are peat-accumulating wetlands that are fed by mineral-rich groundwater. Fens support a high diversity of plants and the BCW corridor has about 500 species of plants and probably more. High diversity of plants naturally supports high diversity of animals as well. The key is the groundwater,” says Amon.

Beaver Creek Wetlands include: Siebenthaler Fen, Koogler Wetland/Prairie Reserve, Creekside Reserve, Beaver Creek Wetland Nature Reserve, Beaver Creek Wildlife Area, Cemex Reserve, Fairborn Marsh, Fairborn Community Park, Phillips Park, Rotary Park and Oakes Quarry Park. All are connected along Beavercreek. More wildlife areas are along Little Beaver Creek and are parallel to the bikeway, like Zimmerman Prairie and Hagenbuch Reserve.

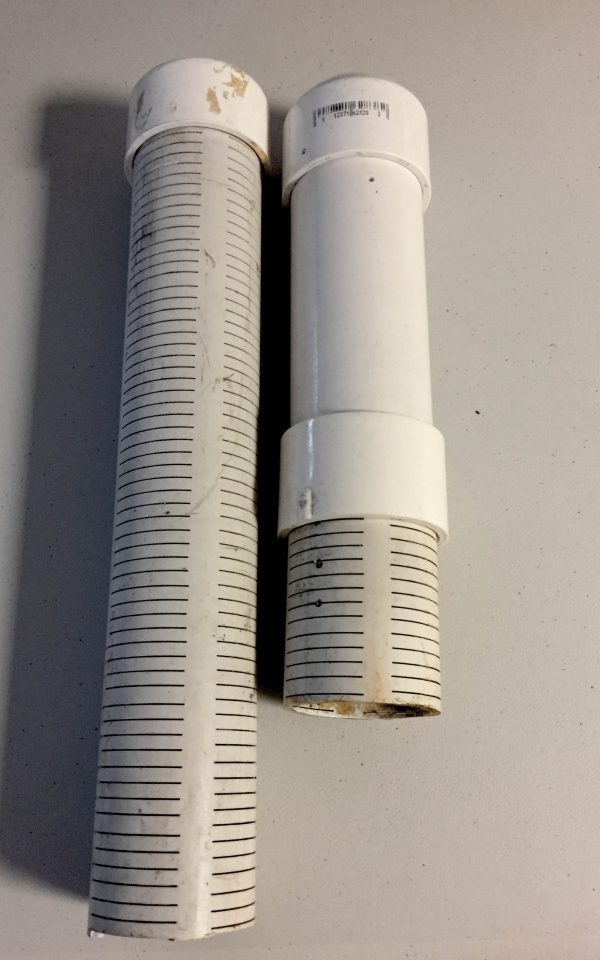

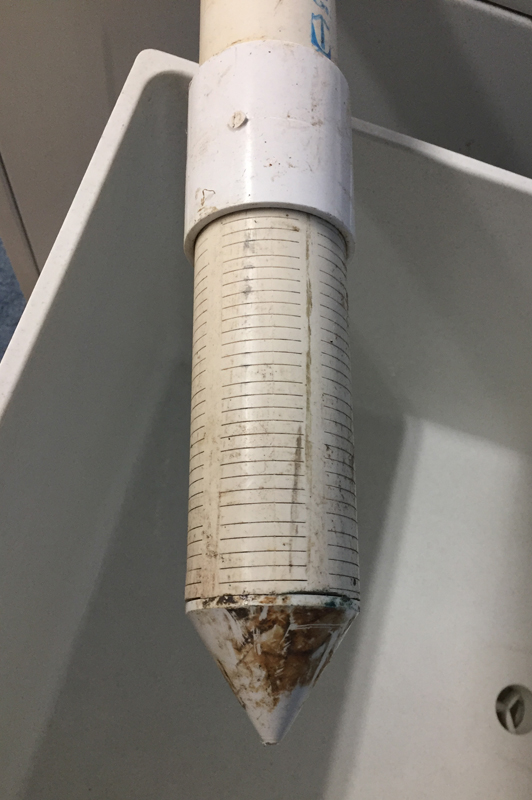

Wells used for water studies at Beaver Creek Wetlands (Credit: Jim Amon)

As Amon explains, “The BCW is a complex of many wetlands stretched out over a more than ten-mile corridor interrupted by only a few roads. Most of the wetlands present are fens or have a strong component of their water source as groundwater. The same aquifer that feeds the fens also is the sole source of water for most of Greene County, Ohio. Volunteers from the Beaver Creek Wetlands Association, formed in 1988, have promoted the conservation of this corridor and while working with grants, local governmental partners, and private contributions buying and restoring or enhancing the amazing variety of habitats there. There are over 11 entry points where the public can examine and enjoy these wetlands. These are described with maps on the BCWA website. The individual parks are owned by a number of local organizations, but the BCWA tries to coordinate most of the ecological management. Trails and boardwalks, often built by those volunteers get people where they can see the unique fens and where students and scientists can do research.”

While there are many things for visitors to see at Beaver Creek Wetlands, researchers there have also found that close visual observation has been key to environmental monitoring of the areas.

“Visual observations are very important,” says Amon. “One key observation we made at one point was that there was some unusually green grass at the outlet of a spring. Upon testing, we found that the phosphate level had become atypical.”

Most of the time, phosphorus readings are so low for wetlands that they cannot be detected with the commonly used field kits such as Hach, Amon says. “The phosphates we’ve measured were soluble phosphorus, the most bioavailable kind. In the summer, our data suggests that runoff that reaches our creek has around 0.5mg/L of that phosphorus. Groundwater that is the main source of water for our fens throughout the year typically has phosphorus at near detection limits for unconcentrated samples – around 0.015mg/L– a big difference,” Amon explains. “For water that soaks into the ground from lawns heavy with fertilizer, phosphorus is likely to be removed by roots and microbes unless it is way beyond their nutritional needs. Getting a rise in groundwater phosphorus suggests fertilizer overuse. The Koogler Wetland/Prairie Reserve, one of our wetlands, is an area where we’ve seen really high phosphorus numbers. We only did one study in that area, so there is a need to repeat and get a year-round look at phosphorus before any firm conclusions can be made, but the plants suggest it is there.”

Tracking down the reason for the high readings has proven difficult. Amon has asked the Greene County Sanitary Engineering people if they ever detected a sewer leak near the Koogler Reserve and they had checked near Koogler regularly but never seen a leak. Since BCWA started its work in 1988 over a thousand homes have been built on the land adjacent to the wetlands and many apply fertilizers to their lawns. The golf course could have been another source of phosphorus, Amon believes. “I recently heard that many lawn care companies are stopping application of phosphorus to lawns as it is known that the soils are essentially saturated with phosphorus and it does little good,” he says. “Nevertheless, we have seen biological indications of eutrophication in some of our wetland areas. Because groundwater moves slowly and over great distances, we may be now seeing phosphorus that was applied decades ago!”

YSI 600XLM sonde used at Beaver Creek Wetlands (Credit: Jim Amon)

Amon has also used a YSI XLM600 sonde to measure temperature, conductivity, salinity, pH, depth and dissolved oxygen in Beaver Creek areas. Such efforts were supported by grants and involved participation by Wright State University students. Students have also monitored the flow of nitrogen and phosphorus through the groundwater of the wetlands and creeks within the BCW corridor and looked at overall groundwater quality. “Beaver Creek Wetlands depend on groundwater,” Amon says. “Much of the monitoring done in the BCW has been to determine background or normal levels of the things we are looking for. Changes get our attention. Water is the lifeblood of any wetland and much of the monitoring we do is associated with restoration projects. You should never begin a wetland restoration project without a strong understanding of the hydrologic regime you are working under. We use two-inch PVC pipe and well screens to make wells and piezometers to check water level and pressure for at least a year-long cycle to know what to expect. Water levels are checked manually with a simple electric water level sensor. One project required over forty wells to get a sense of the hydrology in an old farm field of about four acres. We have used some electronic monitoring of stream conditions where the aquifer is strongly recharged by a wetland constructed for that purpose near a county well field.”

Currently, Amon’s focus is not chemical parameters, however. Monitoring at Beaver Creek Wetlands today primarily involves using biological indicators of wetland health. “After all, that is the endpoint we have to deal with,” says Amon. One biological focus is removal of non-native species, such as purple loosestrife. “Purple loosestrife is a big problem,” Amon explains. “It is very invasive and it is one of the reasons some of our wetland areas have gone from diverse habitats with about 500 plant species to fewer than 12.” Reed canary grass is another highly invasive species that Amon and other volunteers work to eliminate from Beaver Creek.

To directly address the observed phosphorus levels at the Koogler site, Amon and others have been in the process of removing invasive shallow rooted honeysuckle and planting deep-rooted prairie plants in the apparent path of the groundwater. “It is our hope that this bioremediation will soon be mature enough to intercept the phosphorus we’ve seen,” Amon adds.

Techniques for curbing non-native species often involve the introduction of a species that is competitive with the non-native one to prevent recurrence of the invader or using a grass or broadleaf specific herbicide when possible, to avoid collateral damage to “good” plants. Non-native species are sometimes removed using a broad spectrum herbicide like glyphosate (Roundup, etc.) if the non-natives are covering a large area.

Wells used for water studies at Beaver Creek Wetlands (Credit: Jim Amon)

In addition to all the work volunteers do in terms of environmental monitoring and care of Beaver Creek Wetlands, the BCWA is also involved in public education and communicates to people in regulatory agencies that can make a difference in support of the wetlands. BCWA works with people from Greene Soil and Water Conservation, and consider agricultural activities as well. “Some Minnesota and Wisconsin communities have started significant efforts to build rain gardens. Those help with stormwater mitigation and they help protect streams and wetlands. It would be great to start efforts like that in Ohio, too,” adds Amon.

“We are hoping area researchers will get grants to continue doing work that will contribute to Beaver Creek Wetlands, and possibly continue doing chemical monitoring of the wetlands as we have done in the past. Most grants fund more basic research looking for new information that will help us explore new ideas. Monitoring alone does not do this. Our monitoring reveals problems that need action to protect what we have saved. Monitoring should be considered to be part of a larger scale project asking important questions about big ideas that could be funded. We are also hoping to get more student engagement, for example from University of Dayton and Wright State University, and get more university support for our efforts,” Amon emphasizes. “The Beaver Creek Wetlands deserve more research.”

Top image: Baltimore Checkerspot Butterfly (Credit: Mike Mushala)

jarboes

June 7, 2022 at 7:40 am

I agree. Sewer gases backing up into your home can be a severe problem. Sewer gas is a generic term for the noxious mix of chemicals that are the by-product of decaying waste. You’ll know you have a sewer gas problem if you smell the distinct odor of rotten eggs in your home.