Basic Observation Buoy connects students to environment through data collection

Someone within earshot of Lisa Adams while she talks about her water quality monitoring work might wonder how a certain colleague named Bob puts up with her.

“I adopted Bob as my own research program,” they might hear her say, as she did in a recent interview.

And it’s not just her. “His Bob was in a rice field,” she said of one researcher. “They’ve made a Bob on steroids,” she said of another group.

But Adams, an associate professor in the biology and physics department at Kennesaw State University in Georgia, isn’t talking about Bob. She’s talking about BOB–the Basic Observation Buoy. It’s a low-cost, highly adaptable water quality monitoring platform that’s forging a connection between students and their local waterways while helping train the next generation of scientists to gather and interpret environmental data.

BOB began as the brainchild of Doug Levin, who developed the buoy while at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Chesapeake Bay Office as a way to give students a hands-on experience in learning about local water quality.

The platform is constructed from PVC pipe and pegboard. From there, the design and instruments are customizable for whatever purpose, from casual outreach and education to collecting high-quality data for government monitoring programs.

Adams caught wind of BOB after the Southeast Coastal Ocean Observing Regional Association and Centers for Ocean Sciences Education Excellence (that’s SECOORA and COSEE for short) adopted the platform as an outreach tool. In 2009, the groups hosted a BOB workshop and asked Adams to join in.

“They said, ‘Come on down. This is going to be big,'” she said. “We sat around and built buoys for two days.”

After that, Adams joined the cause. She exiled the $13,000 piece of equipment she was using to monitor a tidal creek in South Carolina to a corner of the lab and shifted her focus to bringing the BOB experience to students in the Southeast. She now works to build partnerships between schools and science education centers.

Her first success came in 2010 when she partnered with Angela Taylor, a teacher at Hilton Head Preparatory School, and the Coastal Discovery Museum. The class deployed a buoy in a tidal creek on the museum’s property and used salinity data from PASCO sensors to track tide cycles.

“It was a beautiful partnership between a university scientist, a high school that was just dying to get their hands and feet wet, and an informal science ed center that used it as an outreach tool,” Adams said. “The kids really got into it because the creek was in their backyard. It just became a personal connection and a hands-on experience that was very meaningful for the students involved.”

Lisa Adams and student Chelsea Kuykendall work on a buoy near beaver pond at the Chattahoochee Nature Center (Credit: Michael Dias)

Part of what makes BOB work so well is its versatility, Adams said. The Hilton Head Prep buoy, for example, was powered by a relatively inexpensive meter meant for handheld use tucked into a waterproof Pelican case with a few notches for the sensor cables to run out into the water. The methods and quality control may not be up to EPA standards, but they’re good enough to help students become familiar with working the instruments and data.

But other versions of BOB abound. A University of North Florida BOB program outfitted their PVC buoys with YSI sondes, solar panels and cellular telemetry. Their data meets EPA standards. A University of Connecticut group uses theirs to suspend passive samplers that detect contaminants.

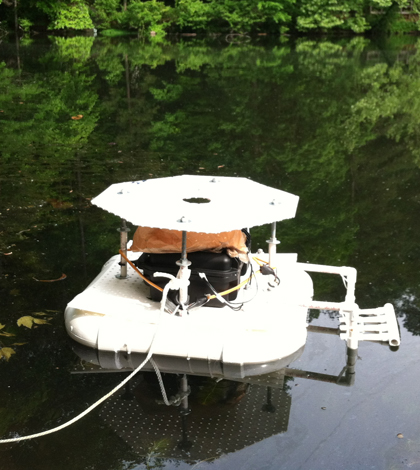

Adams is in the midst of starting a new partnership with the Chattahoochee Nature Center’s Director of Education Tom Howick. This BOB floats on one of the center’s ponds that leads into the Chattahoochee River. The data they collect is posted on the SECOORA website similar to a professional monitoring network’s data portal

“Not only do the students get to collect data for their watershed, but they get to post and share it on the SECOORA site for all to see,” Adams said. “It parallels what a scientist would be doing in a real ocean observing situation like SECOORA does.”

Adams hopes to take student data sharing to another level with her next project, called SPLASSH–Student Programs like Aquatic Science Sampling Headquarters. The plan is to build a social network based on water data that will give students experience of collecting data and sharing it online. Submitting data to a central hub is fairly common practice for professional scientists, but the rigidity of the process makes it difficult to involve students.

“When you think about the big issues like climate change and ocean acidification the future scientists will process vast amounts of data to model and forecast these changes,” Adams said. “But before these students can become proficient data consumers, they must experience data collection for themselves and be data producers.”

Top image: A Basic Observation Buoy float on a Beaver Pond at the Chattahoochee Nature Center in April, 2012 (Credit: Lisa Adams)

0 comments