Buoy monitors melting Mendenhall Glacier’s glacial lake outburst floods

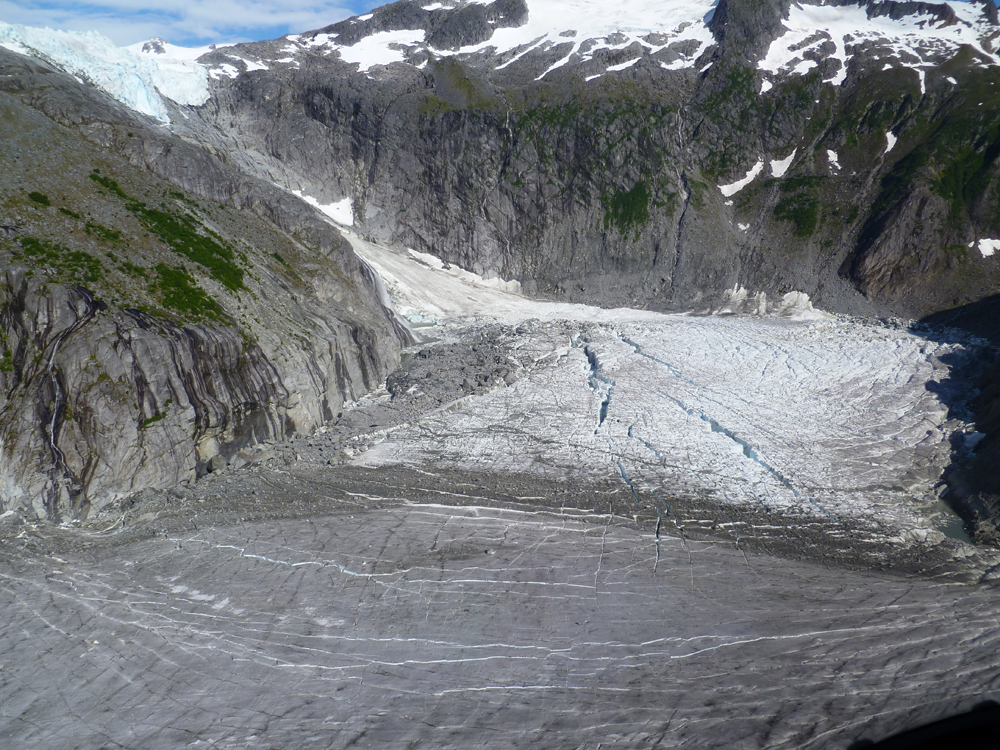

An emptied Suicide Basin near Mendenhall Glacier (Credit: National Weather Service)

In July 2011, around 9 billion gallons of water that had built up behind Mendenhall Glacier near Juneau, Alaska, suddenly burst free, flowing under the glacier and out into the river that flows through the city.

The surge, which flooded basements and submerged trails that access the tourist-favorite glacier, caught the city off guard that year. But it appears the floods will return at least once a year around the same time, thanks to climate-related thinning of the Mendenhall and other ice loss in the system. A July 2014 event that brought Mendenhall Lake to a record high released an estimated 11 billion gallons.

A system of sensors in the basin where water builds up and in Mendenhall Lake is collecting data on the events. The information will help scientists model the timing of outbursts and better prepare the city for the imminent floods.

The phenomenon occurs when formerly ice-filled basin adjacent to the Mendenhall Glacier fills with water, either from rainfall or from melting ice and snow. When the water rises high enough, it floats the glacier and creates an opening through which it flows into Mendenhall Lake, which drains into the river in town.

Some call these events glacial lake outburst floods. Those who do are likely trying to avoid pronouncing the common Icelandic term: jökulhlaup.

“Everyone in Juneau knows how to say that word now,” said Cathy Connor, a professor of geology with University Alaska Southeast. “A lot of people in Iceland can’t even say that word.”

Full Suicide Basin showing cracks in the ice as water underneath pushes up (Credit: National Weather Service)

Connor works with data from the sensor system, which includes a pressure transducer for tracking water levels in Suicide Basin. The basin was once filled with ice and acted as an ice tributary to the Mendenhall Glacier. But it no longer produces enough ice to do so, and instead fills with water behind the glacier.

Data from the transducer shows that the water level there rose by 25 feet beginning on June 30 this year before dropping on July 9. The drop coincided with a rising Mendenhall Lake down-glacier.

Connor also tracks the glacial inflows with a buoy in Mendenhall Lake that supports a string of temperature sensors every 5 meters down to 45 meters below the surface. Contrary to most lakes’ temperature profile, Mendenhall’s surface is usually cooler than deeper waters, a result of floating icebergs that chill the top layer. “It’s a weird setup, but that’s the way it works,” Connor said.

Setting up the buoy on Mendenhall Lake (Credit: Cathy Connor)

But during the jökulhlaup the cold water flowing in from under the glacier inverts that profile, an event the buoy detected on July 11.

“We get a flip, and it’s either cold all the way down or its warmer at the top and cold at the bottom,” Connor said. “So you know you’ve had a blast of glacier water coming in.”

The emergence of these floods is likely tied to the melting of the thinning glacier, which is also receding by about 400 feet per year — a pace that’s anything but glacial.

“You can see over the course of the summer, it’s been exception ice loss,” Connor said. “It’s happening almost in real time now. They’re definitely picking up their pace.”

Top image: An emptied Suicide Basin near Mendenhall Glacier (Credit: National Weather Service)

0 comments