Louisiana’s coastal swamp forests are sinking. Can dredge spoils stop them?

Like many of Louisiana’s coastal wetlands, the bald cypress swamp forests within the Jean Lafitte National Historic Park and Preserve are sinking.

Explanations for the submerging swamps and marshes include sea level rise, the hydrological effects of channelization and canal-building, and even shifting faults beneath the wetlands.

“There are many competing ideas about why this is happening, but I think everybody agrees that the wetlands are sinking,” said Beth Middleton, a research ecologist with the U.S. Geological Survey’s National Wetlands Research Center. “Not all wetlands, but enough of them to be concerned about it.”

One tactic for keeping these important habitats above water is to dredge sediment from nearby waterways and spread it across threatened wetlands, bolstering the elevation and allowing vegetation to take root. That was the intended effect of a 2009 sediment application in two Jean Lafitte National Historic Park and Preserve bald cypress swamp forests. But while these “sediment amendments” have proven effective in saltwater and brackish marshes, the method was untested in this type of freshwater forest, Middleton said.

“I think it’s not only is it an unusual project, but also there are literally no studies of it,” she said.

At the request of the National Park Service, Middleton and her colleagues have spent the past four years studying the effects of the sediment application to the wetland forests. The most recent study of the project was published online by the journal Ecological Engineering in March.

Middleton was well suited for the job because she was already working on a project monitoring the effects of climate change on wetland habitats across the Southeast U.S.

“Which puts us in a position where we can compare how these are growing to elsewhere,” Middleton said. “We know what these things look like and how they generally grow. For us it was really just adding another place in the network.”

A cypress swamp after an application of sediment (Credit: Beth Middleton)

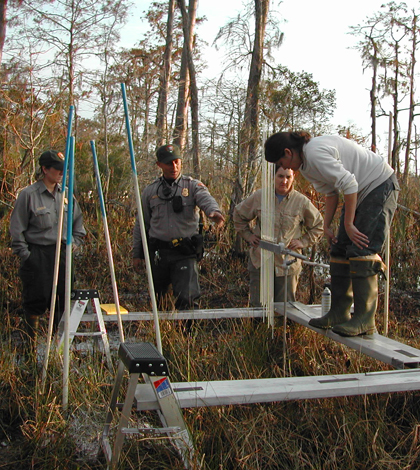

The researchers first needed to know was how much sediment was applied to the swamp. Before the dredge spoils were brought in, Middleton and her colleagues set up a sediment elevation table. That requires driving a metal rod into the soft sediment of the wetland.

“They’re awful to work in, by the way,” Middleton said. “They are truly squishy.”

One goal of sediment amendments is to revitalize a sinking wetlands’ vegetation, so the researchers analyzed the study site’s seed bank and tree growth. The seed bank, a measure of the seeds lying in a habitat’s soil, was particularly important in this case because the new layer of sediment had the potential to bury the seeds and prevent them from growing. A comparison of the test site’s seed bank to an off-site forest’s soil suggests that’s what happened here.

Though some saplings popped up in the years after the application, many were maple and willow trees. Those weren’t the target species for this swamp, Middleton said, but they might still help slow the submerging wetland.

“An argument can be made that those species, since they were growing pretty well, might actually add to the elevation of the place as it sinks,” she said.

The new sediment didn’t appear to boost growth of the forest’s mature trees either. Though the trees did show extra growth in 2010, Middleton suspects that was the result of an effort to mitigate the effects of the Deepwater Horizon oil spill on the Gulf Coast. Extra water was released from the upstream Davis Pond from May to September that year to help push encroaching oil away from shore. That extra water, and not the sediment amendment, is likely what gave the trees a leg up.

“Every other year the trees were almost not growing at all,” Middleton said. “And then we had this blip in the data in that year and it seemed like about the only way we could explain what was going on.”

Middleton is in the process of authoring another paper on the effects of the water release. She said people will likely debate for years to come about whether that was a good idea.

“Very few people were actually looking at what was happening to the non-target areas,” she said. “Everyone was out looking at the oil spill. But we have this long-term project going on and we’re saying, ‘Whoops, what’s going on here?'”

Image: A research crew assembles a sediment elevation table in a bald cypress swamp (Credit: Evelyn Anemaet)

0 comments