Carbon inhaled by Amazon Rainforest is exhaled by Amazon River

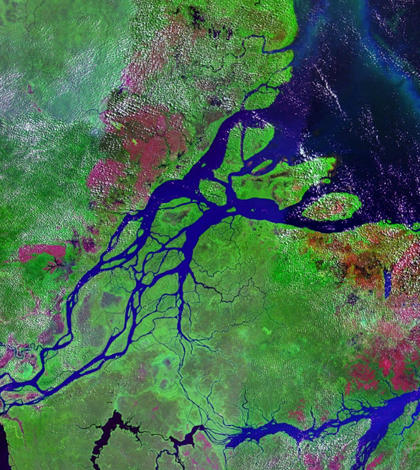

The UW team collected data at the mouth of the Amazon River (Credit: NASA)

The Amazon Rainforest absorbs billions of tons of carbon dioxide from the Earth’s atmosphere each year. The carbon is bound up in the bark and stems that end up washing into the Amazon River. Past research assumed that the woody debris was too tough for the river’s bacteria to break down and release as CO2, but recent work from the University of Washington shows that’s not the case.

Scientists once believed that the river swept away the rain forest’s carbon-laden debris and carried it to the ocean floor, where it was locked away for centuries. But a recently published study from University of Washington oceanographers shows that all but 5 percent of the carbon is digested and released by the Amazon River as carbon dioxide. The team has found that bacteria and fungi are responsible for breaking down the tough forest carbon.

The Washington team partnered with local universities to charter research vessels and ferry equipment during its time in the Amazon. In identifying the main fuel for the river’s carbon elimination, the team shows the inherent balance of carbon transport between land and water and the importance of protecting the Amazon Rainforest in addition to its river.

“The river itself is humongous. At one of the mouths, it’s about 12 kilometers wide. We were out taking samples and you can’t see land,” said Nick Ward, a doctoral candidate in Chemical Oceanography. “There’s tons of water moving and you get tidal shift at the mouth of the river. Every day, twice a day, the river switches directions.”

Despite the shifting waters, Ward says the Amazon River was an ideal choice for the study. Just by size alone, it has global significance — 20 percent of all freshwater in the world flows through it. But it’s also a relatively untouched area. With lower human development along the river, the researchers could look deeper in the natural function of a river.

“Rain falls, saturating the soil, and brings with it pieces of carbon. Once it reaches the river, bacteria – and we’re not sure exactly what kind – and probably fungus continue to degrade it,” said Ward. “Fifty-five percent degrades and turns into CO2. Less than 5 percent is released into the ocean or stored in the watershed. Forty-five percent is broken down in the soils.”

The UW team rented boats to collect measurements and samples at the mouth of the Amazon (Credit: Jeffrey Richey/UW)

To track the transport of carbon from the forest to the river, time-of-flight mass spectrometers were used to identify and measure different compounds in water samples. Ward says the team benefited from technological advances in spectrometry. In the past, a researcher might have only been able to look at 8 compounds. Current technology allowed the structure and quantity of more than 100 different compounds to be determined.

Some water samples taken at the river were analyzed onsite while others were taken back to the University of Washington and allowed to age. Large bits of carbon like sticks or bark were easily pulled out of samples. From there, the samples were passed through various filters to pull carbon out by size.

“We measured a specific type of carbon in this study – lignin. We knew the river was chewing up carbon, but we didn’t know where it came from,” said Ward. “It was typically thought lignin got fixed in trees, soils or flushed into oceans. But these lignin compounds are actually what’s really driving the CO2 outgassing from the river.”

Ward says lignin is one of the most abundant carbon sources on land, comprising about 30 percent. Cellulose, which makes up another 30 percent, acts similarly to lignin and is also broken down by bacteria and fungi.

Growing trees respire in the act of living, says Ward, and deposit carbon in soils. Falling rain moves that carbon into the river, where most of it is eliminated.

“Essentially the land is in balance with the river system. The only real kind of carbon sink is a standing stock of forest,” said Ward. “So by reducing the size of rainforest, we’re reducing terrestrial carbon sequestration.”

Top Image: The UW team collected data at the mouth of the Amazon River, where channels reach 12 kilometers wide (Credit: NASA)

0 comments