Conservation Through Destruction: American Rivers Provides Huge Boost to Nature By Removing Defunct Dams

NJDEP Fish and Wildlife staff perform a fish survey prior to dam removal. (Credit: The Nature Conservancy)

NJDEP Fish and Wildlife staff perform a fish survey prior to dam removal. (Credit: The Nature Conservancy)“There are hundreds of dams all over the country that are no longer serving a purpose. These obsolete dams have no useful function, they damage rivers and can be dangerous for people,” says Laura Craig, Director of the River Restoration Program at American Rivers. “That’s where American Rivers comes in. Along with our partners, we identify dam removals that would provide the most ecological benefit and take them down in the safest way possible. We then use our collective knowledge and expertise to restore the area to its natural state.”

Craig has extensive expertise in dam removal. She has been managing and facilitating dam removals at American Rivers for eight and a half years. She also has a Ph.D. in Aquatic Ecology from the University of Maryland at College Park.

“As an organization, we are engaged in a large number of on-the-ground projects, but our local and regional partners are typically the ones who do the environmental monitoring for our restoration projects,” says Craig. “We jointly choose a suite of metrics that can be used to measure project success, including those focused on hydrology, geomorphology, biology and water chemistry.”

“Dams impact rivers in a few major ways: they impede flow, trap sediment and alter habitat, negatively impact water quality, and prevent the movement of fish and other organisms,” notes Craig. “Removing dams is a type of functional restoration— it addresses an immediate cause of impairment and the end result is a system that is self-sustaining and resilient.”

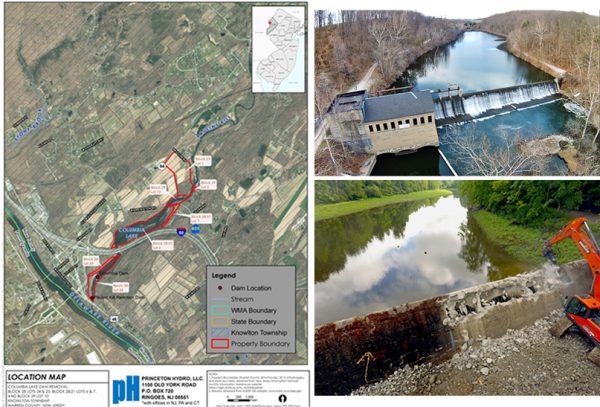

(left) Columbia Dam Project Location Map (top right) Intact Columbia Dam (bottom right) Columbia Dam Removal (Credit: The Nature Conservancy)

“We do work all over the country,” adds Craig. American Rivers is completing dam removal projects with its partners in the Northeast, the Mid Atlantic, Southeast, Pacific Northwest and California.

American Rivers’ partners include local watershed groups and citizen monitoring teams, government agencies like the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, and other national non-profits like The Nature Conservancy. “We also bring in academic researchers to gather data for our projects,” says Craig.

American Rivers gets support from government grants, foundations and major donors. Funding for on the ground projects primarily comes from federal and state grants.

Not just any dam is removed by American Rivers and its partners. “We first must decide which dam removals would do the most good and get owners to support removal,” says Craig. “We prioritize projects that will have the greatest ecological and public safety benefit.” Some of the factors involved in making a dam removal decision are the number of miles of quality habitat that would be reconnected, whether migratory fish are present in a system, and whether there are species of conservation concern, such as Eastern brook trout, that are being impacted by the dam. “We often consider the first barriers to fish: which dams are preventing them from getting into a tributary?” Craig explains. “Overall, we want to reopen desirable habitat that will have the largest positive impact on the fish and wildlife.”

For the Columbia Dam removal project, the major stream affected is the Paulins Kill. Craig is working on this project, but it is being led by an American Rivers’ partner, The Nature Conservancy. “Project partners are monitoring pretty much everything on this project,” Craig mentions, “including geomorphology, water quality, impact on fisheries, riparian vegetation, erosion and metabolism.”

State agencies do fisheries and water quality monitoring for the project.

Thomas Hopper, GIS Analyst at Princeton Hydro installs a HOBO EC digital sensor to monitor water levels in a private well located near the Columbia dam project area. The continuous data collection will provide not only water depth readings but also reveal patterns in fluctuations of the groundwater elevations. (Credit: The Nature Conservancy)

“We started monitoring years before the dam removal,” says Craig. “We were motivated by the fact that New Jersey has no published studies about dam removal. We are aiming to collect several years’ worth of environmental monitoring data before and after the removal of the dam.”

Beth Styler Barry, River Restoration Manager at The Nature Conservancy, shared a summary of the various types of monitoring being done for the Columbia River Dam removal project. Monitoring projects include: shad, sea lamprey and eel monitoring via electrofishing, trap netting, seining, angler creel surveys; spawning/dead fish observations; quantitative data (number of fish, length, weight, catch per unit effort or CPUE) by the New Jersey Division of Fish and Wildlife, along with eDNA collection by the Academy of Natural Sciences at Drexel University. The Nature Conservancy provided macroinvertebrate abundance and sediment monitoring using waders, D-nets/kick nets, sieves, rinse bottles, sample jars, and ethanol. They used EPA’s rapid bioassessment protocol and targeted a variety of permanent monitoring locations to avoid just riffle/best habitats and used the Rapid Habitat Assessment for Turbidity/TSS. A handheld YSI Pro 2030 with a probe for DO, temperature and conductivity supported spot sampling at the Columbia Dam removal site.

Styler Barry adds, “Columbia University’s Aquanauts, a student-led workgroup focused on water resource management and sustainability, used a HOBO EC probe to measure electrical conductivity and temperature above and below the impoundment–in the river upstream, the lake and below the dam downstream.”

One of the top priorities for New Jersey was to help restore populations of American shad, a critically endangered migratory fish. “There used to be millions of shad in the Delaware River watershed. They are sometimes called, ‘The fish that fed the founders,’ as they were plentiful in colonial times and an important food source,” Craig explains. “There is still a neighborhood in Philadelphia called Fish Town, which was once the center of the shad fishery. Lambertville, New Jersey, which is right on the river, still hosts an annual shad festival.” Today, the American shad population is in trouble. There are too many obstacles in its way, preventing it from migrating to historic breeding grounds. “The Paulins Kill is a direct tributary to the Delaware River,” says Craig. “All the information gathered by The Nature Conservancy pointed to the Paulins Kill as being a high-quality river that could help maintain a healthy shad fishery. The Columbia Dam was a great candidate for removal.” Like salmon, American shad live in the ocean but travel to natural freshwater streams to lay their eggs. “The Delaware River at Philadelphia was once so polluted the shad couldn’t get passed the city,” says Craig. “Now that they can move up the river, they are being blocked from the tributaries. Shad have trouble getting over even small barriers,” says Craig. The shad weighs about three pounds and is not a powerful swimmer. They are not as powerful at swimming as salmon are, for example. “We determined that removing the dam would also benefit American eel and resident fishes.”

Dave Keller, Fisheries Scientist at the Academy of Natural Sciences leads an eel survey. (Credit: The Nature Conservancy)

Freshwater mussels also benefit from restoration work by American Rivers and its partners; mussels rely on fish hosts, including migratory fish, for part of their life cycle. “At Columbia Dam, the project team gathered early monitoring data to identify whether mussels were present in the system. We relocated some freshwater mussels to areas with more favorable conditions during construction,” Craig mentions.

American Rivers’ dam removal work has no signs of slowing. “We continue to see growth in the

number of dam removals every year all over the country,” Craig observes.

The U.S. currently has tens of thousands of defunct dams. Many are small, from 5 to 20 feet high, but there are large ones also, from 100 to 200 feet high. Many dams in the U.S. are obsolete, and many are 100 to 150 years old. Many belonged to small mills that either closed or adopted newer technology. Others were used for grain production or for ice production. Many dams are simply abandoned when they are no longer needed. “Dams pose liabilities to owners. The structure can fail. Individuals trying to swim near dams can be fatally trapped by powerful currents,” says Craig. “From a public safety perspective, as well as a wildlife perspective, dam removal is a good idea.”

The more dams removed, the better we become at predicting what the after effects will be: how the rivers will change and what the likely ecological impacts will be. “There are already papers out there that give an overview of how rivers respond to dam removal,” Craig mentions.

Craig has enjoyed her eight and a half years at American Rivers. “I love the variety of the work. I love spending time on the river, leading projects, and even the process of getting permits. I’ve managed dam removals across the Mid Atlantic. It’s work that is so dependent on great partnerships with our design, monitoring and construction teams,” she says.

She also notes that 2019 is the 20th anniversary of the beginning of the dam removal movement. “It all started with the removal of the Edwards Dam in Maine, and it’s been going strong ever since.”

Justin Barton

April 25, 2022 at 8:04 am

Great blog. Enjoyed reading it, very helpful.

Pingback: FishSens Magazine | Restoring Salmon above the Grand Coulee Dam - FishSens Magazine