Cyanobacteria blooms need only a foothold in a lake to alter nutrient cycles in their favor

Call it blue-green algae, pond scum or cyanobacteria, these tiny organisms are forming blooms in water bodies around the world at an increasing rate, and by any name their ability to rapidly damage an aquatic habitat remains. Growing use of fertilizers is partially to blame for more prevalent blooms, but a new multi-institution study shows cyanobacteria can speed the process by influencing a lake’s nutrient cycling in its favor.

The study took the form of a literature review and model, incorporating data from previous studies detailing cyanobacteria behavior in New Hampshire and Maine. It appears in the scientific journal Ecosphere.

“What this paper shows is that cyanobacteria has the potential to have strong impacts on both phosphorus and nitrogen cycles in ways that have been appreciated for a long time within particular fields of aquatic ecology, but may not have been appreciated in the broader community,” said Kathryn Cottingham, professor of biological sciences at Dartmouth College and lead author of the study.

“It draws attention to the consequences of cyanobacteria blooms in lakes where we have not historically drawn attention to them.”

But for the past 15 years, cyanobacteria has drawn plenty of attention to itself in northeast New England. Cottingham said she contributed to a study of one particular taxa that formed “really large colonies” in the region. Her research revealed that those colonies could fix nitrogen while acquiring sediment phosphorus and moving it into the water column, effectively bioengineering the lake to better support their own growth.

“Based on our studies of that particular organism, we began asking how general that phenomenon might be,” Cottingham said.

As it turns out, many cyanobacteria taxa display the ability to influence nitrogen and phosphorus cycles to their benefit, one of the new study’s findings that Cottingham calls “surprising.” In fact, she said, this phenomenon could likely occur anywhere that cyanobacteria bloom.

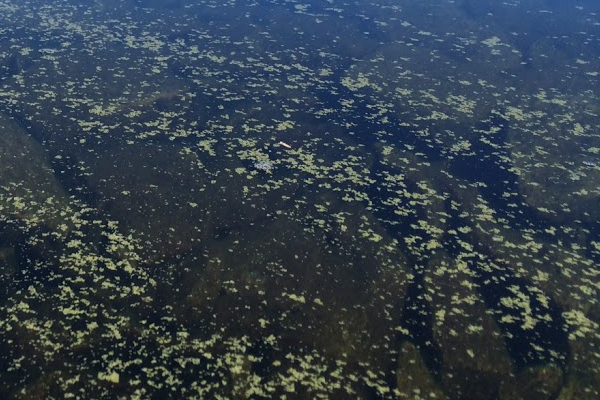

Gloeotrichia bloom in Lake Sunapee, NH. (Credit: Samuel B. Fey)

The discovery means more than greater bloom rates. When tailored to the tastes of cyanobacteria, a lake’s phosphorus and nitrogen cycles can form positive feedback loops that help blooms grow while intensifying the effects of chemical runoff and climate change. This increases nutrient availability for the cyanobacteria even further, perpetuating a cycle that can damage delicate aquatic ecosystems. And the issue isn’t limited to water bodies located near cities or agricultural activity, either.

“We’re seeing more and more problems in areas where the watershed is still forested and development is still early in terms of human use,” Cottingham said. “I think of them as a warning sign that these lakes may not be as clear as they have been historically. Some of the systems we studied are actually used as drinking water sources without filtration.”

Increased blooms in areas of low land use suggest that other factors, such as climate change, are playing a role in these watersheds, helping cyanobacteria establish a foothold — and with the ability to regulate nutrient cycles, a foothold is all cyanobacteria needs to form massive colonies. However, Cottingham said she and her colleagues faced some resistance publishing the study, possibly because of perceptions regarding those other factors affecting watersheds.

“There was concern that diverting attention to cyanobacteria would take attention away from what’s going on in watersheds,” she said. “One of the messages I want to be sure gets through is that what’s going on in watersheds is critically important, and cyanobacteria will amplify those effects.”

Cottingham intends to continue studying cyanobacteria, with hopes to improve nutrient measurement resolution and glean the mechanisms that cause blooms to occur at all. If that can be uncovered, she said, it may be possible to stop the “supply chain” responsible for the blooms’ growth.

“That’s a really ambitious agenda,” she said, “but it would be cool if we could pull it off.”

Top image: Gloeotrichia bloom in Lake Sunapee, NH. (Credit: Samuel B. Fey)

Pingback: Study: Algal Blooms Optimize Conditions To Support Growth - Lake Scientist