Deltas in Decline: Mapping the Retreating Seafloor of the Mississippi River Delta

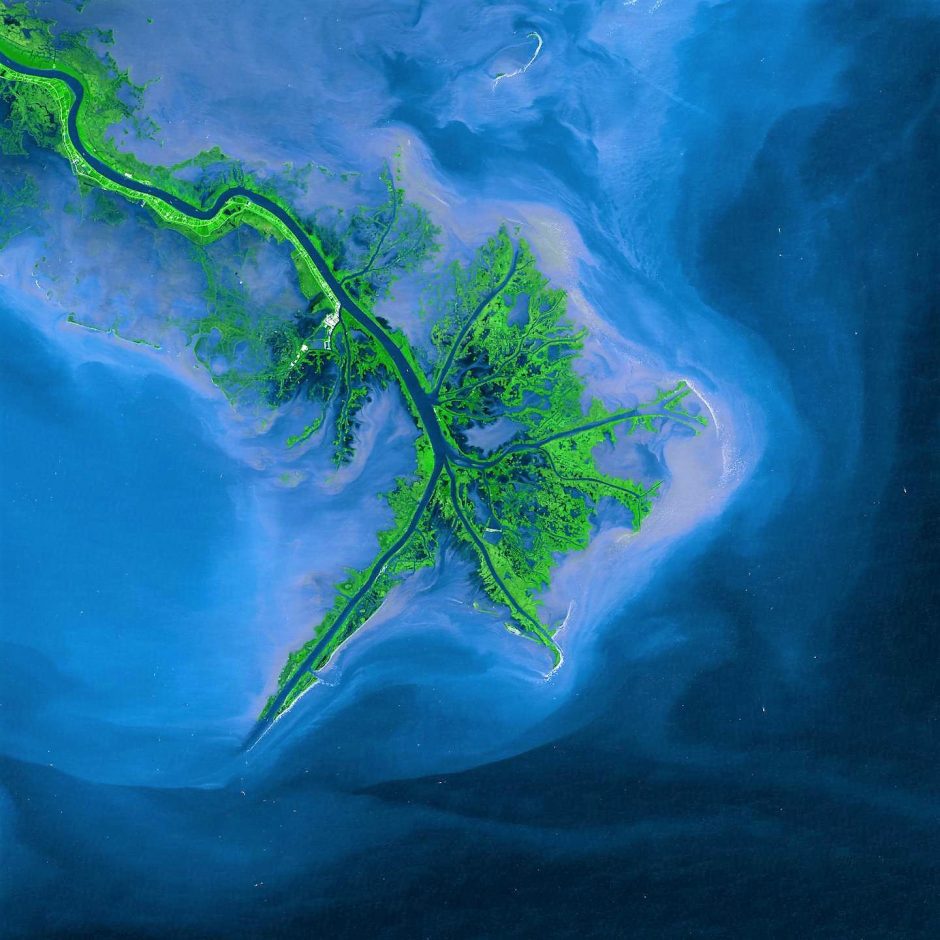

This image shows the Mississippi River Delta in 2001. (Credit: NASA)

The rapid coastal land loss that the state of Louisiana has been experiencing over the past century has been reported on many times. We know that Louisiana loses about 1 football field’s worth of land every hour, and that some of the first “climate change refugees” in the US are coming from Louisiana as towns like Isle de Jean Charles disappear into the water.

New research from a Louisiana State University (LSU) team reveals that land loss is also occurring underwater. The disappearing seafloor in the Mississippi River Delta (MRD) is threatening various marine flora and fauna, and contributing to pollution in the Gulf of Mexico. The team mapped the shrinking seafloor in their study, detailing the effects the loss is having on the region. Lead author Jillian Maloney, who conducted this research as a post-doctoral researcher at LSU and is now an assistant professor at San Diego State University, corresponded with EM about the work.

Culling the data

The team culled data for their study from academic research, historic nautical charts, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) underwater mapping projects, and research from the oil and gas industry, all collected between 1764 and 2009.

“We had access to digital seafloor data from regional mapping in 1874, 1940, and 1979,” details Maloney. “These were part of Dr. Coleman’s work from 1980 and they were also used by a collaborator, Dr. Guidroz, for a more recent dissertation. The other datasets were obtained by working with our partners and from publicly accessible databases. We were limited in our comparisons because regional surveys were not conducted regularly; for example, the most recent regional survey was completed in 1979. For more recent observations we had to combine several smaller surveys, and even then we do not have a complete picture.”

Even so, the study was fairly comprehensive, despite the many challenges the team faced with their data.

“One difficult part of doing this research was that the datasets we compared were collected across the span of over a hundred years,” details Maloney. “During that time, technology to map the seafloor has changed dramatically. Because of this we made sure to include some measurement of uncertainty in our results. It’s also important to note that the last major regional survey was conducted well before the development of multibeam sonar. Multibeam sonar can map large swaths of the seafloor at very high resolution, with little interpolation between points. These data are incredible at showing the fine-scale features of the seafloor. A new regional survey of the delta using this technology would greatly enhance our understanding of the ongoing changes to the seafloor, and also of the landslide activity on the delta front.”

In some sense, given how much the Mississippi River has been engineered and modified, it’s not surprising that the team found the MRD has entered a stage of decline. However, the change is noteworthy, because the MRD had been spreading naturally for centuries before human intervention started this decline.

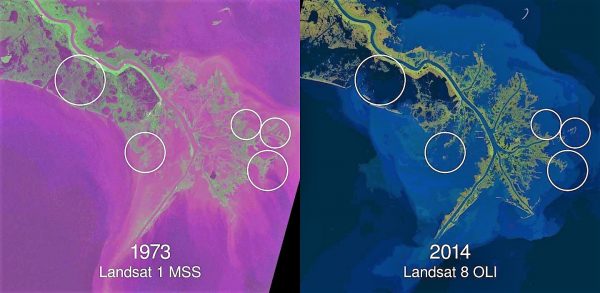

This image shows four decades of coastal land and wetland loss in the Mississippi River Delta, as observed by Landsat (USGS/NASA Landsat Program). (Credit: Zachary Tessler. Data: USGS/NASA Landsat Program)

“We did expect to find the delta in decline, primarily because of the historic reduction in sediment delivered to the delta due to dams and other modifications to the Mississippi River system,” remarks Maloney. “However, this decline has never been verified or mapped in any way, so the extent and patterns of seafloor change we observed are interesting.”

The team determined the sites along the coast they’d study based on an existing project looking at seafloor landslides.

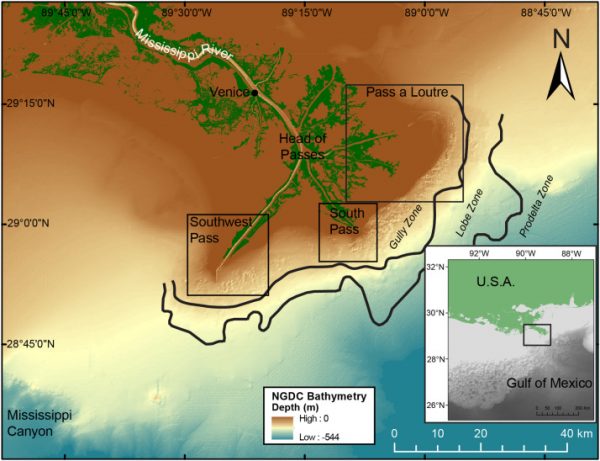

“We were focusing generally on the area of the seafloor where these landslides have been mapped (known as the delta front),” explains Maloney. “This is also the area of the underwater delta that has been growing into the Gulf of Mexico for hundreds of years. We also specifically looked at the seafloor near the three main outlets of the Mississippi River where most of the sediment is delivered into the Gulf of Mexico.”

Connecting the decline and human activity

This kind of decline can be caused in part by many contributing factors, some of which might be a natural part of a delta’s lifespan. However, in this case, there appears to be a connection to human river engineering.

“It’s difficult to really pinpoint the cause of the decline because there are so many factors, both natural and human-caused, that could be contributing,” clarifies Maloney. “What we did find was that the decline appears coincident with the reduction in sediment in the Mississippi River, which is a function of human modifications to the River.”

Other deltas around the world are going through similar depletions, and the team hopes that their work can be used to help scientists discover these declines around the world.

“We anticipate that these changes are occurring on other deltas because we see similar patterns of reduced sediment in those river systems,” remarks Maloney. “The parts of the Mississippi Delta that are above the water are also in decline, and we see that pattern repeated across other major deltas as well. Based on the similarities of reduced sediment and decline of the landward portions of deltas, we anticipate that those deltas are also experiencing similar changes to the delta beneath the water.”

Overview map of the Mississippi River delta showing major passes and offshore bathymetry (Love et al., 2012). Black lines represent the boundaries between the mudflow gully, mudflow lobe, and prodelta zones, which are labeled Gully Zone, Lobe Zone, and Prodelta Zone and italicized. Three small black boxes highlight the three major passes, which are the study areas in Fig. 4. Inset shows regional map with black box over delta location. (Credit: Maloney et al.)

Moving ahead, the team is looking forward to more work on the Mississippi River delta.

“As I mentioned before, this is part of a project to study the submarine landslides on the delta front,” adds Maloney. “One of the next steps could be to learn about how the reduced sediment and decline of the delta front are impacting landslide hazard.”

This process has global implications for delta ecosystems, not to mention and geological, biological, and chemical processes.

“Rivers are the major transporter of sediment from the land to the sea and the sediment that is transported also contains nutrients, carbon, possibly pollutants, et cetera,” describes Maloney. “If we are seeing that the major river systems of the world are experiencing changes to how that sediment is deposited or eroded in the ocean, then we would expect that the way those things are cycled through earth’s systems might also be changing. The changes to the seafloor could also impact patterns of seafloor habitat and marine ecosystems.”

0 comments