Deploying a New Weather Buoy System With NOAA

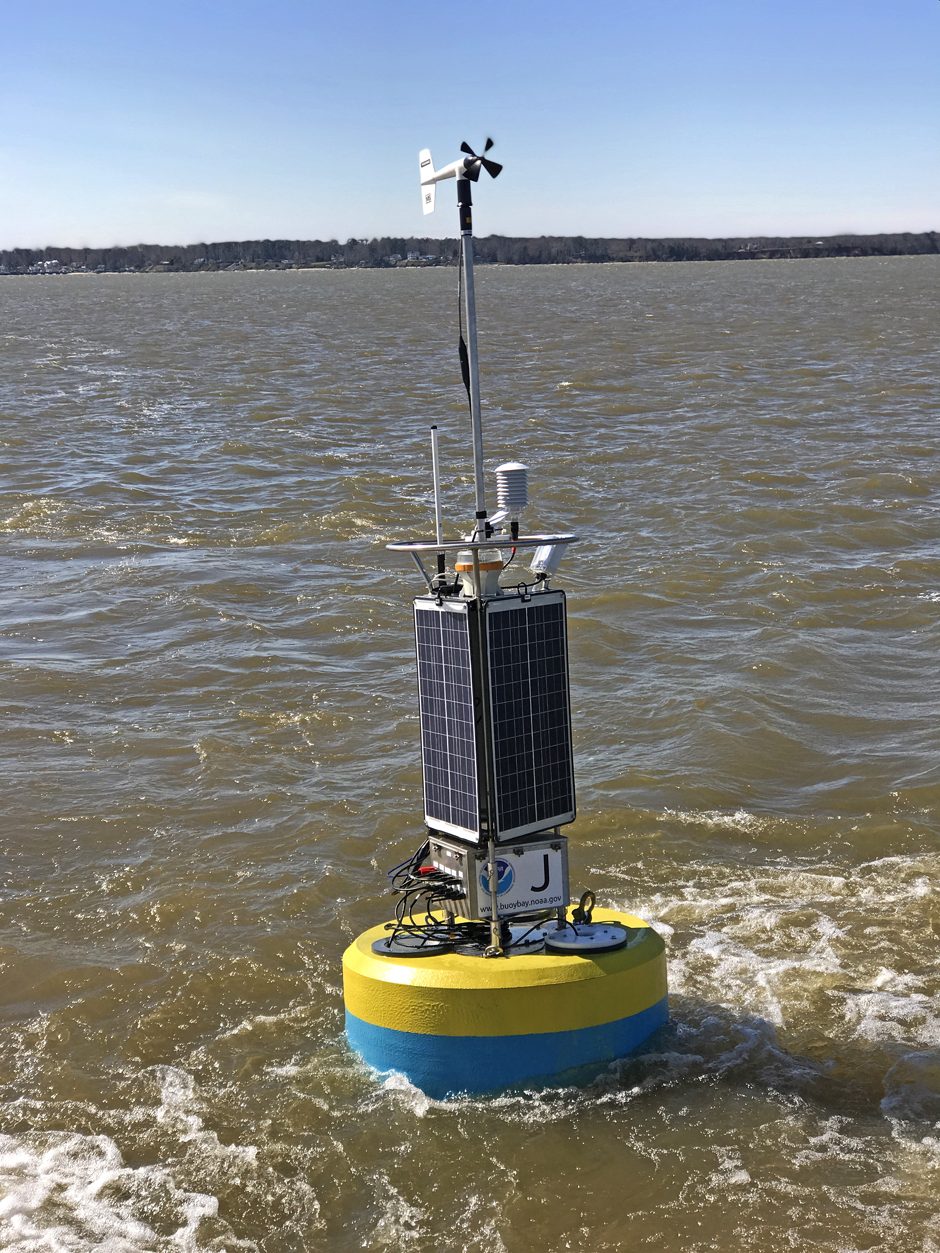

The buoy, deployed in the bay, now taking readings on selected parameters. (Photo Credit: Fondriest Environmental)

For the past two years, the NOAA Chesapeake Bay Office has been partnering with Fondriest and NexSens to phase out their AXYS data buoy systems with NexSens CB-1250 data buoy systems. Several members of the Fondriest team recently visited and participated in a buoy deployment on the Chesapeake Bay, and Byron F. Kilbourne, an oceanographer at the NOAA Chesapeake Bay Office and liaison for the deployment, spoke to EM about the office, their team, and the buoy change.

“The NOAA Chesapeake Bay Office was initially formed as a NOAA liaison to the Chesapeake Bay Program, which is a federal partnership with the states for the management of the Chesapeake Bay, and it’s led by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA),” explains Dr. Kilbourne. “Every other federal environmental program or office has a liaison to the Chesapeake Bay program. The USGS, EPA, Department of Interior, US Fish and Wildlife, and NOAA all have program offices.”

NOAA’s Chesapeake buoys have an unusual origin story that is almost entirely unrelated to their current mandate. The National Park Service (NPS) had spearheaded an effort to create the John Smith Water Trail—a kind of aquatic Appalachian Trail for boaters in the Chesapeake. The Department of Education funded this NPS idea as a form of environmental outreach, and the buoys were to serve as interpretive trail markers along the trail.

“It had this weird beginning, and then the oceanographer in my role back in 2005 said, ‘If we’re going to have buoys out there as interpretive trail markers, we should have some observations on them so that we can deliver that data to the people using the trail markers,’ the current temperature, or whatever,” details Dr. Kilbourne. “That idea kind of grew, and they built this really interesting observing system of buoys which were deployed starting in 2007.”

The R/V Rachel Carson, from the University of Maryland on its way to deploy a monitoring buoy (Photo Credit: Fondriest Environmental)

Over the years the water trail didn’t generate the interest that people hoped, but its buoys continued to support the NOAA observing system in the Chesapeake Bay. Eventually, the system became a set of 10 full-time stations.

Lighter buoys, better data

In the past, the NOAA Chesapeake Bay team used the AXYS WatchKeeper buoy.

“They’re fine for some environments, or for programs that have their own vessel operations capabilities,” Dr. Kilbourne describes. “We have a zodiac-type open boat and another boat that’s a little bit bigger, but neither is up to the task of deploying the AXYS buoy, so we have to contract all that out.”

According to Dr. Kilbourne, the AXYS buoys weigh in at around 4,500 pounds each including anchor.

“You don’t have to lift all that at once, but the amounts that you do have to lift are heavy enough that most of the ships that can do that with no problem have a pretty deep draft,” remarks Dr. Kilbourne. “Most of the areas that we’re working in are pretty shallow out of the way. The program budget for those kind of vessel operations is pretty low, so the bigger boats that can handle that equipment with no problem would chew up our annual vessel contract budget in one trip.”

It has been a challenge for the team to find vessels that can handle the AXYS buoys over the years within budget, and this has led them to struggle to respond to various problems in a timely way.

“The NexSens buoy brings us the flexibility to bring our vessel operations in-house, or even if we’re still using contractors, it really broadens the spectrum of vessels that are appropriate for the job,” adds Dr. Kilbourne.

The biggest difference in the two buoys for the NOAA team during the deployment process is weight, not total size.

“The NexSens CB-1250 buoy is lighter, although the way we’ve customized it from top to bottom it’s actually a little bit bigger in total length,” states Dr. Kilbourne. “However, we’re able to totally instrument the buoy, and have it completely plugged in and sampling, as if it was in the water, on-deck. This way we can pick it up from the side, and drop the whole buoy in, tested, working and ready to go and be done with it. The whole deployment, from the time we get on-station to the time we’re driving away, is less than an hour.”

Adjusting mooring set-ups before hitting the water. (Photo Credit: Fondriest Environmental)

Although the team cannot pick up the NexSens buoy in the same way, retrieving it is still a simpler process due to its lighter weight.

“We can pull the superstructure off in one lift, and then we can pull the buoy up in one lift, and it’s greatly simplified our operations here,” remarks Dr. Kilbourne.

Simplicity hasn’t been the only benefit to making this change, however. Easier deployment and retrieval also means better, more reliable data and improved performance.

“What the smaller buoys have brought us in terms of reliability is pretty huge, because we can service these with the vessel we already have,” Dr. Kilbourne says. “A day or so after we got the Jamestown buoy in the water, we’re not sure how, but the buoy got pulled up into the shallow mud that was in the riverbank there, and we had to go and pull it back off. We did that with our own vessel and not with a contractor, so that was a huge help with our operations. Because of the buoy, we were able to respond in a timely way. That’s a huge help to our maintenance effort.”

More monitoring power, better use of data

Now the team will be phasing in customizations such as SeaView Systems SVS-603 Wave Sensors that they are planning to phase in over the next few years. Even with more monitoring power, the team will be working to put the data to use more effectively.

“In 2009, then-President Obama signed an executive order called Chesapeake Bay Protection and Restoration, and that order gave NOAA the lead on observing the Chesapeake,” explains Dr. Kilbourne. “This buoy program became the only tangible effort that NOAA had in support of this protection and restoration executive order, and that is how this program is currently funded. It’s super popular with the users, and I try to bring that cost down.”

NOAA Chesapeake Bay Office staff secure an anti-rotation collar to the buoy for extra protection while deployed. (Photo Credit: Fondriest Environmental)

There is a bottom line cost to operating a program like this that has very little to do with buoys and much more to do with the people who work with them.

“We have to have a facility to operate from, we have to have vessels, we have to have trucks to pull those vessels, we have to have lifting equipment, forklifts, so there’s a baseline cost,” details Dr. Kilbourne. “Whether we have one buoy or whether we have 50 buoys running in some geological area that you can service from at least one field facility, the baseline cost of about $850,000 a year remains. Even with only one buoy, you’d need one technician, one oceanographer or other scientist, and one person to do all the software on the back end.”

For the NOAA team, one of the questions is how to get more value out of the data and the program—and how to do more with the data.

“The data supports a lot of recreational and small scale commercial use,” Dr. Kilbourne describes. “It also supports commerce in the sense that there are marinas and other businesses driven by recreational use. It is incorporated into the weather service for their marine forecast for the Chesapeake. But it’s not in NOAA’s system that helps direct commercial and other ships into port and it’s not in current use by either the Maryland or the Virginia Pilots’ Associations to guide ships into port. To the best of my knowledge, it’s not published anywhere in the academic journal record. And it’s not used to do ecological forecasting, such as trying to predict harmful algal blooms.”

Part of what Dr. Kilbourne has been working on is making those connections and improving the quality of the data record so that potential users feel it can be trusted.

“It’s a 10- or 11-year record that we have at this point, and I have done all the archival quality control, if you go to the National Center for Environmental Information there’s a download,” remarks Dr. Kilbourne. “It’s all in NetCDF format so anyone can download the data, and it’s flagged according to good, bad, suspect, or not-examined for quality control. I think they can be relied upon. And it’s also totally documented, so if anyone ever disagrees with my assessment they can look at the method and they can make their own call.”

The fully integrated and powered data buoy ready for deployment. (Photo Credit: Fondriest Environmental)

“The other way to get more value out of it, in my opinion, is to add more stations,” adds Dr. Kilbourne. “Adding more stations doesn’t cost a lot more. A lot of the cost of the program is fixed, so the upfront cost of funding the equipment out to 15 buoys from 10 doesn’t cost a lot more operationally.”

Finally, Dr. Kilbourne has been trying to make the case that the NOAA team should conduct research in the Chesapeake when they have downtime and are not busy maintaining the buoys.

“When I was a graduate student and a postdoc, I found that when it comes to models, datasets that are created in support of some idea that is investigated separately are often very useful,” states Dr. Kilbourne. “For example, I wrote a paper about a storm that I experienced in the Southern Ocean when I was a graduate student and the impact of that storm on some observations that we were making around that time. I was able to say, ‘This is the two week period that I was there, and these are the measurements that we made during that time. We don’t have any other data, but we have this long record of simulated winds for the whole earth. And if we look at this two weeks, and the impact of this two weeks, we can make some assumptions about the broader scale.’”

0 comments