Diatoms Dominate Muskegon Lake In A Cold And Rainy Year

A phytoplankton sample from Muskegon Lake. (Credit: Jasmine Mancuso)

A phytoplankton sample from Muskegon Lake. (Credit: Jasmine Mancuso)Climate change-driven volatility is changing lakes at the base of their food webs.

That’s one way to interpret new research that documented such a change in Muskegon Lake on the coast of Lake Michigan. Researchers found that, in one particularly rainy and cool year, normal phytoplankton diversity and patterns were cast aside. Instead, one group of algae dominated the entire year, offering a glimpse into the kinds of surprising changes that could happen in the future.

“Phytoplankton are a very responsive group of organisms,” said Jasmine Mancuso, whose research detailing the change in the lake was published in October in the Journal of Great Lakes Research.

While many understand climate change to mean continuously warmer weather, Mancuso said a key part of the picture is increased instability, which might include stretches of colder, wetter weather. Her research shows how lakes might respond.

Cold, wet and full of diatoms

The area immediately surrounding the Muskegon Lake watershed had one of its wettest years on record in 2019. It was also an unusually cold year, according to data from the Muskegon Lake Observatory Buoy, which has been collecting water quality data since 2010.

The Muskegon Lake Observatory Buoy. (Credit: Jasmine Mancuso)

When phytoplankton samples were examined, it was clear that the plankton community in the lake had a unique makeup dominated by diatoms. Mancuso explained the anomalous phytoplankton community using climate data.

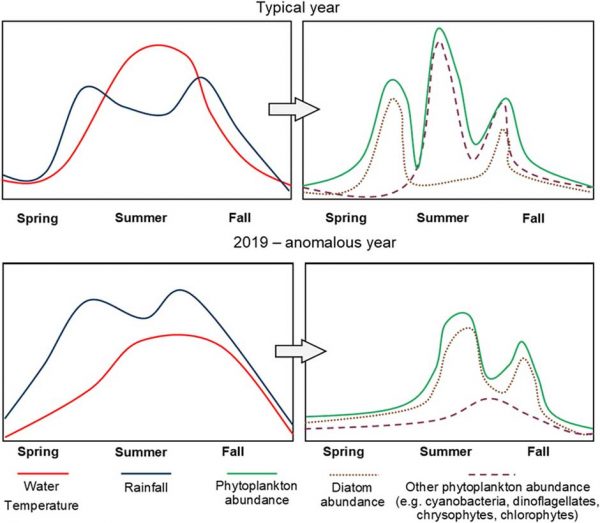

Diatoms, one of the world’s most bountiful phytoplankton, typically are the most abundant group of algae in Muskegon Lake in the spring before other groups of phytoplankton grow more plentiful. After waning in the summer, they become more abundant again in the fall, though they are accompanied by other groups of algae. The lake typically has three spikes in phytoplankton abundance, consistent with patterns seen in other temperate lakes. Diatoms dominate only for the earliest when the water is cool and well mixed.

In 2019, Everything was Different.

Mancuso found that diatoms were the most abundant group of species for the entire year and that the typical three-spike pattern was absent. Her research suggests a couple of reasons colder and wetter weather could boost diatom populations.

The lake stratified in late June, much later than normal due to the cool, long spring. Increased rainfall helped water cycle through the lake faster throughout the year. Frequent rainstorms also kept the water column well-mixed throughout the year. These environmental conditions favor diatoms over the other types of algae that dominate the lake later in a typical year.

In 2019 Muskegon Lake saw more rainfall, cooler water and an anomalous phytoplankton community. (Credit: Journal of Great Lakes Research/Elsevier)

Climate changes for Lake Food Chains

One cold, rainy year was likely enough to make big changes at the base of Muskegon Lake’s food web, but her research didn’t look to document any effects in the organisms that feed on phytoplankton.

Diatoms are one of the favorite foods of certain fish, so the shift documented in 2019 could actually be a positive for some fish, said Bopaiah Biddanda, a professor of water resources at Grand Valley State University and Mancuso’s advisor. Even if some species of fish might have benefited from a large presence of diatoms, any substantial change to the food web could disadvantage others and have negative consequences throughout the ecosystem, Mancuso noted.

Most years in the late summer, Muskegon Lake is also affected by harmful algal blooms dominated by cyanobacteria. In 2019, the diatom-dominated lake had a much-reduced cyanobacteria bloom. Conditions that favor diatoms (cool and well-mixed water) specifically disadvantage cyanobacteria (which prefer warm and stratified water).

While 2019 was a surprise event and research of effects up the food chain didn’t occur in this study, it surely has some effect.

“Those are definitely food web consequences,” said Biddanda. “What the plankton are, is what the fishes end up eating.”

A phytoplankton sample from Muskegon Lake. (Credit: Jasmine Mancuso)

Volatility up and down Lake Michigan’s coast

Muskegon Lake is a drowned river mouth estuary, a fairly common type of lake along Lake Michigan’s eastern coast, Mancuso said. That could mean the effects seen in this lake happened elsewhere in the region during 2019 as well.

Climate change means that the lake may experience more climatic variation in the future, especially in terms of both temperature and precipitation.

“The water cycle is the one that goes most haywire,” Biddanda said.

That could mean—though it’s impossible to predict exactly—more disruption to phytoplankton communities in the future, with consequences for the entire food web. Share on X“The effects of warming are going to be patchy,” Biddanda said. Changes seen in one year may not be replicated at a different time or in a different place.

Though the effects on phytoplankton (and lakes as whole units) are difficult to predict, climate change makes events like those in 2019 much more likely.

“Climate change has repercussions,” Mancuso said.

0 comments