DNA Testing for Legionella Can Identify Source of Outbreaks Quickly

Illustration of Legionella pneumophila, the bacterium that causes the majority of Legionnaires’ disease cases and outbreaks. (Credit: CDC, https://www.cdc.gov/legionella/resources/materials.html)

Legionnaires’ disease is the deadliest waterborne disease in the US, and since 2000, incidences of the serious lung illness has jumped by 300 percent. The State of New York is hardest hit by the disease; in 2017, more than 40 percent of cases originated in New York.

Given the conditions favored by the Legionella bacteria that causes the disease, that’s no surprise. According to the Centers for Disease Control (CDC), outbreaks are most common in structures with complex water systems, such as hospitals, hotels, long-term care facilities, and cruise ships. Older structures that rely on dated water systems and cooling towers are at risk.

Fortunately, Christopher Boyd, General Manager of the NSF International Building Water Health Program, is on the case. Formerly the Assistant Commissioner of Environmental Sciences & Engineering for the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, he led the agency’s response to the largest Legionella outbreak in the history of New York City.

Now, Boyd is putting DNA analysis to work in order to prevent more outbreaks and help to usher in an American water safety culture.

Using DNA to respond to a crisis

In 2014 and 2015, Boyd and his team had their hands full. First, in late 2014, 12 people in the Bronx were diagnosed with the disease. The team was able to track the disease back to its source: a housing development’s contaminated cooling towers.

In July and August 2015, another distinct outbreak in the Bronx killed 16 and sickened 138 people. This was the deadliest outbreak in American history. The source was once again a cooling tower, this time on top of a hotel. A third outbreak in the Bronx happened in late September 2015, causing one death and 13 sick. The disease was again traced back to cooling towers.

However, what has often been missed in the discussion of these outbreaks was the swift response from New York City health officials, a response powered by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) DNA testing. This method enabled the team to identify the source of the outbreaks within hours of collecting specimens—a far cry from the standard bacterial culture method, which typically takes five to 10 days.

This success story was the first time PCR was applied to the Legionella problem. While PCR, unlike culturing, can’t reliably reveal whether the bacteria present are living, when it is used after an outbreak has already started, that’s less important. Once people are already getting sick, the response team knows some of the Legionella is alive, and the main challenge is to respond sooner to the threat in a targeted way.

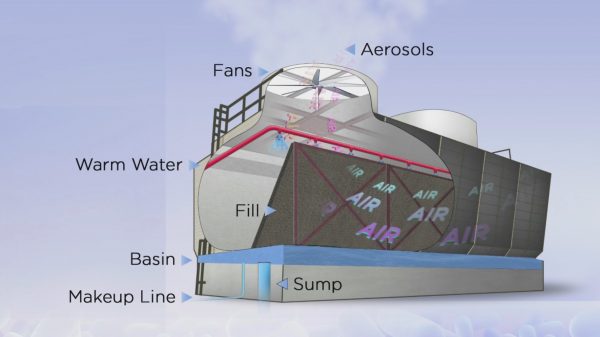

Various species of Legionella thrive in cooling systems and are a growing threat as American infrastructure ages. (Credit: By CNX OpenStax (https://cnx.org/contents/5CvTdmJL@4.4) [CC BY 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0)], via Wikimedia Commons)

Quelling future outbreaks faster

The CDC promulgates sampling procedures sampling procedures for use during Legionella outbreaks. Public health officials collect water samples and biofilm swabs at points of use, in cooling towers, in water heaters, and in whirlpools and such points of contact with water. At each site, the team measures parameters including temperature, pH and chlorine levels. Finally, samples are cultured for Legionella.

The PCR technique replaces the culturing taking place over days back at the lab, but the PCR method offers additional benefits. For example, there are different strains of Legionella, and although one strain might be causing an outbreak at any given moment while another might not, any other live strain found is also potentially dangerous.

“Multiple strains of Legionella can cause illness and live Legionella in a cooling tower is cause for concern,” states Boyd. “An NSF International protocol, NSF P453, provides cooling tower owners with clear direction on how to manage and respond to risks within a cooling tower, including specific actions that must be taken based on the volume of live Legionella. NSF P453 was issued as a protocol to quickly provide guidance to cooling tower owners in the wake of the large outbreak in New York City. NSF P453 will be incorporated into a landmark NSF International standard currently under development—NSF 444: Prevention of Illness and Injury from Building Water Systems—which will be a NSF/ANSI voluntary standard that can be adopted by states and cities and used as a best practice by the private sector.”

On the other hand, finding dead Legionella in a water source might be good news for an investigating team.

“It is not uncommon to find dead Legionella in a cooling tower; in fact, that is an indication that the water management is working,” adds Boyd.

Cooling towers are often the problem when it comes to Legionella, but there are effective tactics for managing the risk they pose.

Cooling towers, which are often part of the air conditioning systems of large buildings, are a common source of Legionella exposure in outbreaks. Cooling towers need to be properly maintained in order to prevent Legionnaires’ disease. (Credit: CDC, https://www.cdc.gov/legionella/resources/materials.html)

“While cooling towers have been repeatedly found to be the source of large community Legionella outbreaks, there are viable and cost-effective solutions for managing risks from cooling towers,” explains Boyd. “Cooling towers can be managed in a manner that both protects public health, improve the life expectancy of the cooling tower system and improve its energy and water efficiency.”

The most effective approach starts with creating detailed public health strategies for dealing with Legionella, including knowing were all cooling towers are and setting regulations for how they are managed.

“Building owners can safely and cost-effectively manage cooling towers to meet public health goals,” details Boyd. “However, when an increase in Legionnaires’ disease is identified, public health departments should have a registry of cooling towers and information on compliance with maintenance requirements to speed environmental investigations. Similarly, the public health departments should have standard response protocols in place to help ensure consistent response, risk communication, direction to building owners and organizing their overall public health response.”

In fact, the CDC finding that 9 out of 10 Legionella outbreaks are almost completely preventable with more effective water management is not about, for example, spending to get entirely new water systems without cooling towers; it’s about putting these public health plans in place.

“The CDC’s finding reinforces what environmental health and water engineering professionals widely knew based on their ability to control and prevent outbreaks from building water systems: with properly designed and implemented water management plans, Legionnaires’ disease outbreaks are preventable,” Boyd clarifies. “The past practice of taking corrective action after the identification of sick and dead people is no longer tenable. Corrective action should be taken in response to water quality data that indicates an elevation of risk to prevent the onset of illness and potential morbidity from Legionnaires’ disease.”

Chris Boyd speaking May 10 at Legionella Conference 2018 in Baltimore, sponsored by NSF International and the National Science Foundation. More than 450 people attended and heard presentations from 40-plus scientists, engineers and other experts on all aspects of managing Legionella in building water systems. (Credit: Karen Jackson, via communication with Andrew Henion)

This strategic change is part of a drive to make public health a preventative, planning discipline rather than a reactionary discipline. The trend in public health is toward better planning with solid science to prevent outbreaks, and that’s a trend that teams like Boyd’s are fueling.

“Correct!” Boyd remarks. “Building water systems should be actively managed to prevent illness and injury. The paper on the use of PCR to improve reaction times, the CDC finding that 9 out of 10 outbreaks are preventable, the CDC finding of widespread evidence of Legionella in cooling towers, the Center for Medicaid and Medicare Services direction to healthcare facilities to develop water management plans to reduce healthcare-associated illnesses, and NSF P453 and NSF 444 are all part of an effort to improve public health outcomes by being proactive rather than reactive. When we are done, it will no longer be acceptable for sick and dead people to serve as the sentinel data that trigger an investigation into waterborne disease outbreaks.”

Top image: Illustration of Legionella pneumophila, the bacterium that causes the majority of Legionnaires’ disease cases and outbreaks. (Credit: CDC, https://www.cdc.gov/legionella/resources/materials.html)

0 comments