Ducks Unlimited Works Hard to Conserve and Restore North Atlantic Wildlife Habitat

State University of New York-College of Environmental Science and Forestry students release American black ducks fitted with telemetry equipment, as part of a joint research effort to study the ecology of black ducks and mallards in New York’s Finger Lakes region. The Black Duck Joint Venture, Ducks Unlimited and New York State Department of Environmental Conservation participated in the study. (Credit: State University of New York)

State University of New York-College of Environmental Science and Forestry students release American black ducks fitted with telemetry equipment, as part of a joint research effort to study the ecology of black ducks and mallards in New York’s Finger Lakes region. The Black Duck Joint Venture, Ducks Unlimited and New York State Department of Environmental Conservation participated in the study. (Credit: State University of New York)From conserving 1,700 acres of coastal New Jersey to restoring a former Massachusetts cranberry bog, Ducks Unlimited has successfully implemented multiple large conservation projects in their 12 state North Atlantic region, partnering with multiple organizations and private landowners to conserve and restore critical wildlife habitat that supports waterfowl, fish and amphibians. “Ultimately, when we support wildlife, we support people too,” says Chris Sebastian, Public Affairs Coordinator for Ducks Unlimited, covering the North Atlantic and Great Lakes regions. “We all need clean water to drink and uncontaminated food supplies. Wetlands act as nature’s kidneys and clean up pollution in a highly effective way. They are extremely valuable.”

One important program of Ducks Unlimited in the North Atlantic is their Completing the Cycle Initiative, which is meant to address the needs of Atlantic Flyway waterfowl over their entire life cycle. By taking steps to support their habitat throughout the year, Ducks Unlimited strives to keep birds healthy and capable of “completing the cycle” and returning to their breeding grounds to reproduce successfully.

The Completing the Cycle Initiative is of great importance because so much wetland habitat has already been lost due to East Coast human population growth and activity. The region has lost about 7 million historical acres of wetlands in the Maine-to-Maryland region. Thirty-four waterfowl species travel through or winter in the area, including Atlantic Brant, American Black Ducks, Black Scoters and Canvasbacks. About 7.6 million breeding waterfowl use the Completing the Cycle Initiative areas.

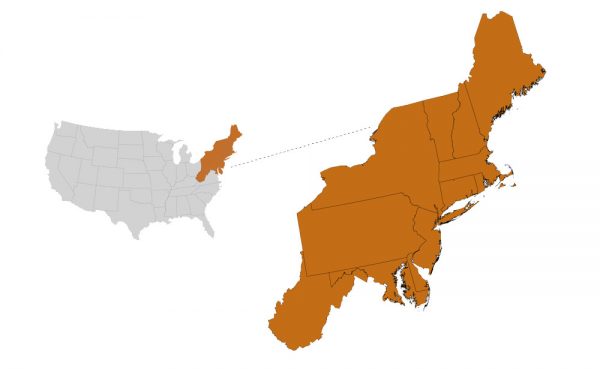

The North Atlantic Ducks Unlimited region is shown here on a map. (Credit: Ducks Unlimited)

The New England, or North Atlantic, region of Ducks Unlimited stretches over a 12 state area from Maine to Maryland, including states such as Pennsylvania and West Virginia. “These 12 states are important to people and ducks,” says Sebastian. “About 21 percent of the U.S. population is in these states. After about 300 to 400 years of development, about 60 percent of the original wetlands have been lost. They are still being lost. So it is critical to try to conserve and restore what we still have.”

Ducks Unlimited looks at the impact of conservation on the landscape, and the impact on fisheries and waterfowl. They do many large conservation projects that restore habitat, including creating passages for fish that open up wetlands. They also protect and restore wetlands by monitoring and removing invasive species. “One of the big invasive species we monitor for is Phragmites,” says Sebastian. “Phragmites tends to outcompete native plants and saps the food native wildlife relies on. However, Phragmites can be managed by varying water levels. Human interference in an area can lead to the water level staying the same, which Phragmites likes. However, natural wetland areas aren’t always wet: they’re supposed to go through a wet-dry-wet-dry cycle. Once we have managed to restore that cycle in a wetland, we get control over Phragmites and the wetland native species can return.”

Ducks Unlimited restored Del Reeves Marsh in Connecticut, a 25-acre freshwater emergent marsh in the central part of the state. The project was in partnership with the Connecticut Department of Energy and Environmental Protection (CDEEP) and the North American Wetland Conservation Act and is part of a larger conservation effort by CDEEP to restore and protect 2,175 acres of critical wetland habitat the coastal boundary area of Connecticut (Credit: Ducks Unlimited)

Ducks Unlimited, in coordination with its partners, monitors human impact in the region, such as from farming. Wetlands slow down and even stop the formation of deposits from agriculture in the region. Ducks Unlimited has conserved about 202,000 acres in the North Atlantic area while monitoring the impact of boating and fishing in the area. Intensive engineering and surveying work is performed. Ducks Unlimited also partners with a conservancy to purchase land for conservation, including land from private landowners. “We use scientific methods to determine what the best parcels of land would be to purchase, from a conservation standpoint,” says Sebastian. “Not every parcel will give us the best conservation value for our dollar, so we have to be careful in terms of what land we decide to purchase.”

While conservation and restoration benefit many species, there are a few that Ducks Unlimited is working especially hard to protect. “In the North Atlantic region, we are especially trying to save the American Black Duck,” says Sebastian. “Birders and hunters are both fond of it. It’s a large bird that’s enjoyable to watch, and it has a historical and cultural impact in this area.” The American Black Duck is found in the Eastern U.S., breeding in Canada and wintering in Virginia, Kentucky, Georgia and Florida. “In the Upper North Atlantic, you can see it all year,” says Sebastian.

Another species of interest is the Canvasback Duck. “In Maryland, in the Chesapeake Bay area, the Canvasback has an important role in the culture. It’s also a large and beautiful bird.”

Marsh birds are being monitored before and after restoration. Rails and bitterns are two bird species of interest.

Ducks Unlimited is in the third phase of its Southeast New Jersey Coastal Initiative, a $4 million

effort to protect or enhance 1,772 acres of coastal wetlands. This 121-acre tract of land will become part of Supawna Meadows National Wildlife Refuge (Credit: Ducks Unlimited)

In the North Atlantic region, Sebastian notes that Ducks Unlimited is doing more and more conservation project monitoring. “It’s not our area of expertise, though,” he says. “We rely on our partners to do the monitoring, including federal and state agencies. We work with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, local municipalities, the Nature Conservancy in New England and the State University of New York, to name a few.”

Speaking about his monitoring work for one such partner organization, State University of New York-Brockport Research Scientist Greg Lawrence indicates it’s not just ducks and marsh birds that are important species of note. “We primarily get frogs and toads on our calling amphibian surveys. During early spring, we get a lot of Spring Peepers, Northern Leopard Frogs and American Toads, while we get Bullfrogs, Green Frogs and Gray Treefrogs later on in the season,” he says. Amphibian monitoring is done by boat at night.

Vegetation monitoring is performed in fens, cattail and sedge meadow environments using vegetation transects. Vegetation monitoring is performed using drone aerial imagery of transects. A Trimble RTK GPS system is used, which can give super accurate, centimeter-level measurements at altitude.

Ducks Unlimited participates in conservation activities in many ways, from gathering scientific data to using heavy equipment in the field, moving the dirt and getting the job done. “We have a full conservation shop, including surveying and engineering,” says Sebastian. In addition to the regular staff, students are involved with Ducks Unlimited. They gather water quality samples and perform other tasks. The Ducks Unlimited team as a whole has a great impact. “Ducks Unlimited has conserved more than 14 million acres across the country,” says Sebastian.

Ducks Unlimited and the Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management – Division of Fish & Wildlife restored 190 acres of wetland habitat at Great Swamp and Woody Hill Wildlife Management Areas. Division of Fish and Wildlife staff observe the project site. (Credit: Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management – Division of Fish & Wildlife)

Ducks Unlimited is also supported by many volunteer-based organizations. “We do dinners, we pool our fundraising money with partners, and we also get large grants from the North American Wetlands and Conservation Act. The grants are typically about $100,000 to $1 million,” says Sebastian. “We also get thousands of acres of land granted to us.” Generally, Sebastian says, “It’s a huge team effort at Ducks Unlimited. We invest lots of time and science into our work.”

Public Affairs Coordinator at Ducks Unlimited for three years, Sebastian began his career in journalism and was once a reporter for the Times Huron in Michigan. He covered water and environmental issues in the Great Lakes region. “I was ultimately drawn to Ducks Unlimited because I liked working outdoors, and I wanted to influence the field of conservation more. This has been a great place for me,” he says. “It’s a great feeling to see all the work we do come together.”

For more information on Ducks Unlimited conservation efforts:

https://www.ducks.org/conservation/du-conservation-initiatives/completing-the-cycle-initiative

0 comments