Earthquake sensors help track endangered whales

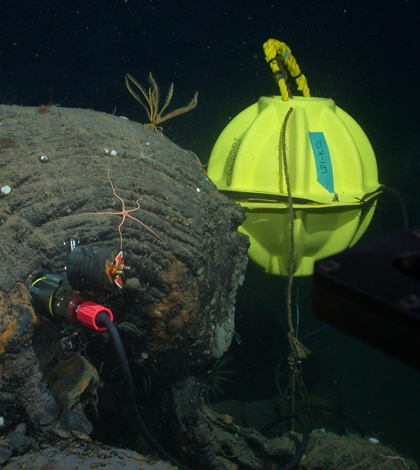

A seismometer inserted into a hole drilled in seafloor lava (Credit: John Delaney and Deborah Kelley, UW)

Tagging endangered whales for research is a controversial practice. The leviathans of the deep are mammals, just like humans, and many people believe they have feelings and experience pain just the same.

In response, researchers from the University of Washington have come up with a way to track whales without tagging them. They use seismometers – earthquake sensors – to track the creatures’ movements in the deep blue sea.

By following vibrations from sounds the whales make and calculating time between seismometer recordings, it’s possible to triangulate the mammals’ locations. Knowing their location and movement patterns could help shipping vessels avoid hitting the endangered creatures, one of their biggest threats.

The network of seismometers that the researchers use was originally put down for volcanic study, to listen to earthquake cracks and monitor changes in rock and hydrothermal fluid. It was installed with a remotely operated vehicle on Juan de Fuca Ridge, a seismically active zone off the coast of Washington state.

The seismic sensors used for tracking have been snugly buried in hardened lava near the seafloor. They’re placed in a cylinder which is inserted by the remotely operated vehicle into a hole about 15 inches deep and two inches in diameter.

“Sounds travel through the ocean at about a mile per second. A whale can make sounds tens of meters deep,” said William Wilcock, professor of Oceanography. “Seismometers record the direct sound and echoes that reverberate off the sea surface that help us triangulate the whales’ movements. At the same time, we’re also recording earthquakes.”

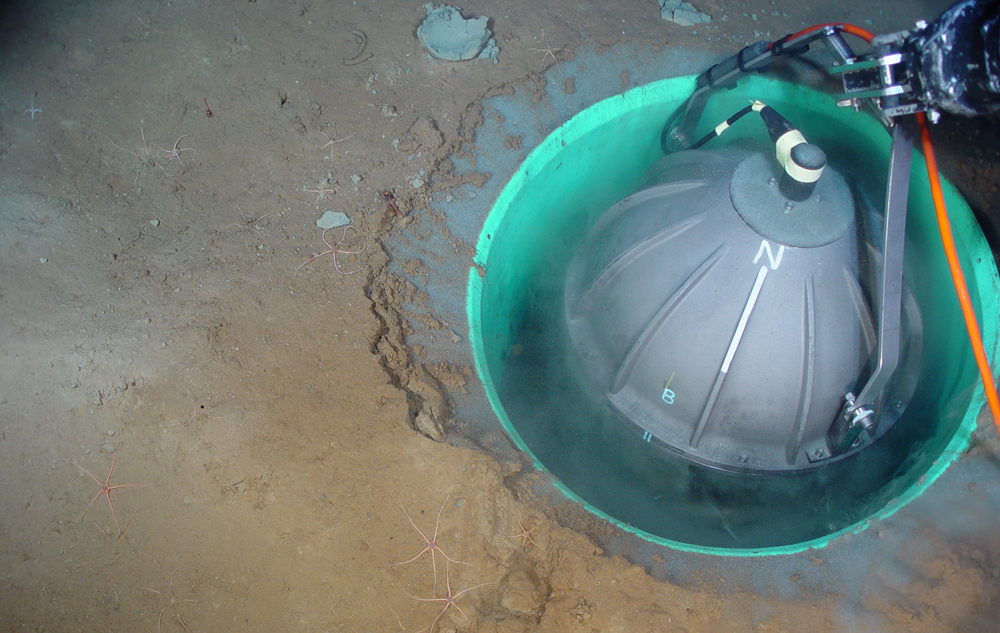

The remotely operated vehicle ROPOS being recovered by the R/V Thomas G. Thompson with a short period seismometer package developed by the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute held by the manipulator arm. (Credit: Mitchell Elend, UW)

Wilcock says that the recorded sounds give a clue to different calling patterns. By looking at those patterns, he says, the whales’ behavior can begin to be inferred. The team gets most of its data from fin whales because they are slightly more abundant than more endangered blue whales.

The seismic sensors are designed to listen to sounds at 1-200 Hertz, says Wilcock. Impulsive sounds come from earthquakes, while monotonous sounds come from whales.

“Sounds are different from fin whales, at about 20 Hertz,” said Wilcock, noting an interesting communication pattern between two fin whales. “One vocalized every 25 seconds and the other would occasionally pop in. Eighty percent of communication was coming from one whale.”

A Guralp broadband seismometer in a housing developed by the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute being placed into a hole in sediments on the seafloor near the Endeavor Segment of the Juan de Fuca Ridge (Credit: Deborah Kelley and William Wilcock, UW)

Acoustics are a very powerful technique to cover a large area, says Wilcock. One limitation, however, is that researchers can’t be there in person to observe the whales. But researchers are making discoveries in associating sounds with particular behaviors. One of his students determined about 150 tracks of fin whales vocal over the fall, winter and spring seasons.

“We found groups of whales swimming north quickly, which was surprising because of the typical behavior of baleen whales to take in lots of food in high lots,” said Wilcock. “They usually go south to breed, but these were heading in the opposite direction.”

Top image: A seismometer inserted into a hole drilled in seafloor lava. Eight of these instruments were installed at an ocean spreading-center volcano 150 miles off Vancouver Island. (Credit: John Delaney and Deborah Kelley, UW)

0 comments