East African Rift Carbon Emissions Are Significant

Lake Magadi, an alkaline lake that contains soda, is located in southern Kenya near the East African Rift. (Credit: University of New Mexico)

It seems like scientists are always working to make the global climate budget more accurate. And of course they consider sources like the burning of fossil fuels. But what about the sources that come from Earth itself?

A study led by researchers at the University of New Mexico has zeroed in on one area of our planet known to be a big emitter of carbon dioxide: the East African Rift (EAR). Through their work, the scientists made a straightforward estimate of just how much carbon that the rift is pumping out each year. Coming to the total then helped in making another determination — that emissions from burning fossil fuels each year dwarf those coming from the rift by a factor of 500.

What does this finding mean? Well, it certainly shows just how much gunk humanity can throw into the air. But it also puts things into perspective, underscoring the idea that more attention should be placed on emissions from fossil fuels. Still, emissions coming from nature are important to quantify so that models and research projects studying the issue can have more accurate info on which to base their findings.

Heading into the work, the scientists knew that they would find emissions of carbon dioxide, partly due to the rift’s location near several active volcanoes and anoxic lakes. But they weren’t sure how big the outgassing would be.

“Although volcanism is thought as the main source to release deep CO2 to the atmosphere, we wanted to know how continental rifting contributes to CO2 emission without volcanism,” said Hyunwoo Lee, doctoral student in the Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences at the university and lead author on a paper detailing the study’s findings.

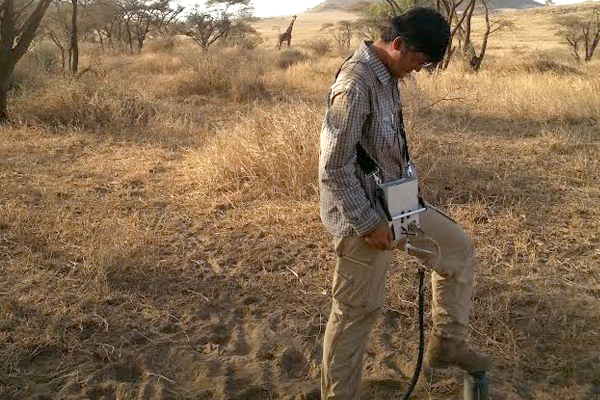

Lead author Hyunwoo Lee gathers carbon dioxide samples at the East African Rift with some of the native wildlife in the background. (Credit: University of New Mexico)

To dissect that total, he and others on his team used EGM-4 carbon dioxide gas analyzers along the East African Rift to capture quantities of carbon dioxide in glass vials. These were then analyzed back in the lab in New Mexico using infrared analyzers. Lee says that seismic data were also gathered by a team member through a network of seismic sensors in the CRAFTI network (Continental Rifting in Africa: Fluid-Tectonic Interaction).

The results of the analysis showed how the East African Rift is contributing to the global total of carbon dioxide, namely that it is emitting more than had been previously thought.

“Based on our C isotope and seismic data, the EAR releases magmatic CO2 (deep CO2) along faults away from volcanic centers. Our estimated CO2 flux from the EAR is about 71 megatons per year, which is comparable to that of mid-ocean ridges (which release 53 to 97 megatons per year),” said Lee. “(For perspective), total deep CO2 output has been reported as 637 megatons per year. See how much we got! For sure, we were really surprised and excited.”

For comparison’s sake, Lee mentions that the emissions coming from the East African Rift are more than those coming from the San Andreas fault in California.

Those findings will prove useful for global climate modelers who need the most accurate emissions data they can find. But Lee says how he and others went about getting the results may also help other scientists working on similar issues.

“Like I said, CO2 output from deep sources (magma or mantle) can be better quantified by our study,” said Lee. “We suggest a way how to investigate CO2 flux in continental rifts, such as the Rio Grande rift (in the United States) and the Baikal rift (Russia). Hopefully, people will report more CO2.”

Funding for the work was provided by the National Science Foundation’s Tectonics Program. Also contributing were scientists from University of Idaho, University of Rochester and the University of Nairobi.

Top image: Lake Magadi, an alkaline lake that contains soda, is located in southern Kenya near the East African Rift. (Credit: University of New Mexico)

0 comments