Edge-of-field monitoring in Lake Erie tributary watersheds to bolster nutrient modeling

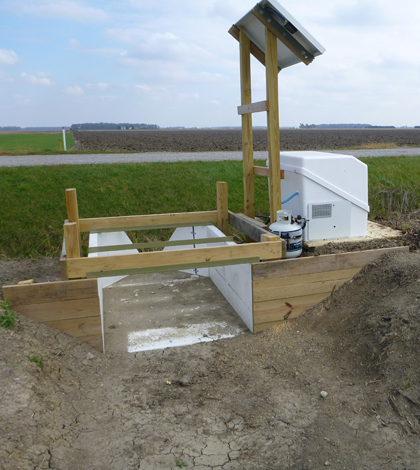

A USDA edge-of-field monitoring station in the Sandusky Watershed (Credit: Kevin King)

A historic upswing in phosphorus deposition in the watersheds of a Lake Erie tributaries has a group of Ohio and Texas researchers monitoring the nutrient at its source, just as it runs off of farm fields as fertilizer.

Heidelberg University’s National Center for Water Quality Research received a three year $590,000 U.S. Department of Agriculture grant. Remegio Confesor, a research scientist at Heidelberg and principal investigator for the project, said researchers will collect data for a seven years on two farm fields no smaller than 10 acres during two crop rotation cycles.

USDA partners will collect the runoff data, while a team from the Texas Institute for Applied Environmental Research will enter the data into the USDA Agricultural Policy Environmental eXtender, or APEX, model. The APEX model, which estimates watershed dynamics, will be applied to the Sandusky Watersheds to determine nutrient loading characteristics in Lake Erie.

Around thirty percent of phosphorus that enters Lake Erie from fertilizer or manure is in the dissolved phosphorus form. Dissolved phosphorus is 100 percent bioavailable, making it prime pickings for algae, Confesor said. “The problem that we had is that the rise of this dissolved phosphorus coincided with the recurrence of algae blooms in the lake,” he said.

The edge-of-field sites include flumes to facilitate sampling (Credit: Kevin King)

The research will benefit from 35 years of historical data on the Maumee and Sandusky watersheds collected by Heidelberg along with help from the Sandusky River Watershed Coalition and other sources. That monitoring began after harmful algae bloomed in Lake Erie in the 1970s. The problem then was sewage overflows were sending excess nutrients in the water and feeding the algae.

A change in upstream sewage treatment practices caused dissolved phosphorus levels to decline until the 1990s. Since then, the levels of dissolved phosphorus have increased in Lake Erie.

The USDA will manage the edge of field monitoring stations, which will collect water quality data at runoff drainage points. “We have installed flumes and weirs at the edge of field and end of tile and connected automated water samplers on those devices to periodically pull water samples,” said Kevin King, USDA agricultural engineer. “The samples along with the amount of water moving through the flumes and weirs will help determine the amount of nutrients being lost at the edge-of-field sites.”

The stations include Isco samplers (Credit: Kevin King)

Various fertilizing and nutrient reduction techniques will be tested for their effectiveness. The researchers will simulate no-till fertilizing, tilling and crop rotation.

Current fertilizer applications allow easy nutrient runoff as many farmers deposit the fertilizer on the soil’s surface. Confesor said injecting nutrients into the soil would work the best to prevent runoff. However the method still needs to be developed further to be feasible for all farmers.

Once the study is complete, the team will use the information they’ve gathered to create recommended best management practices.

Confesor said it will not be easy to get farmers to change their ways. However, new methods developed by the study may ultimately reduce the loss of nutrients spread on the soil, which translates to less cost for fertilizers for the same yield of crops.

Top image: A USDA edge-of-field monitoring station in the Portage Watershed (Credit: Kevin King)

0 comments