Elliott Bay Reconstruction Benefits From Chum Salmon Finds

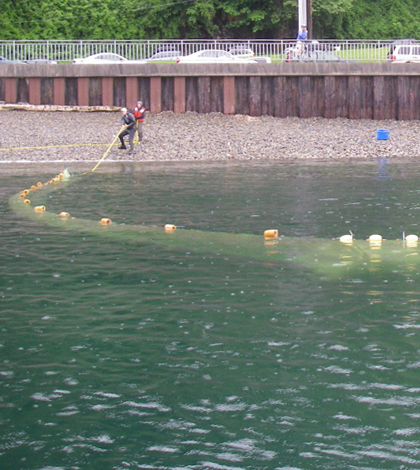

U. of Washington researchers enclose an area of water next to a restored beach at Seacrest Park in Elliott Bay to collect young salmon. (Credit: Stuart Munsch / University of Washington)

Like many commercial waterfronts, Seattle’s Elliott Bay has been built to withstand the natural forces of erosion. This has come with the addition of structures like concrete seawalls and piles of riprap, most of which were put in place in the 1930s.

But there are a few manmade beaches that have sprung up in recent years along its banks. Some of these have come about because the city is reworking the shoreline following an earthquake that occurred around 10 years ago. And moving forward, Bay planners are looking to add still more improvements, including complexities in seawalls, underwater benches in the intertidal zone and a new beach, all of which are meant to help support fish habitat.

The enhancements will likely be good for fish, as the results of a University of Washington study has found that the existing armored shorelines have effects on the types of food fish can take advantage of. The investigation looked only at chinook, pink and chum salmon and uncovered interesting changes in the types of prey specifically available to chums around armored and unarmored areas.

“We know that a lot of the things they (chum salmon) like to eat are produced offshore in sandy, bottom habitat that has been replaced by concrete,” said Stuart Munsch, a doctoral student in the school of aquatic and fishery sciences at the university. “They like harpacticoid copepods, that are these little invertebrates that like to hang out at the bottom, in sandy substrate. Well, armoring gets rid of that since there’s no habitat.”

A juvenile Chinook salmon’s stomach is flushed so researchers can see what the fish ate recently. (Credit: Stuart Munsch / University of Washington)

To investigate what sort of effects the different shoreline types had on the food choices of salmon, scientists tugged large seine nets around sections of the bay. Typically, one end was pulled by a boat while the other was held by cohorts standing on shores. The boat completed a half-circle-shaped voyage in the areas, which gathered fish for analysis.

Once the fish were netted and collected onshore, Munsch and other scientists used hoses to clear out their stomach contents and look at what they were eating. For the chinook and pink salmon, there wasn’t much variation in what they ate regardless of where they were netted. But researchers found that chum salmon caught along armored shores tended to have different food in their guts when compared to those netted near manmade beaches.

“The major findings were that we found different prey availability at beaches versus shorelines,” said Munsch. “The fish eating those (copepods) would switch to a different prey that might be harder to find or maybe less nutritious. We don’t know yet.”

In explaining why chum salmon were most affected by the shifts in habitat, Munsch says that they are mostly shoreline oriented and prefer to eat prey that like sandy or algae-prone areas. Because of that tendency, as well as results of past studies into the impacts of armored shorelines, he and others really weren’t surprised by their findings.

But the results could help inform restoration work going on in and around Elliott Bay.

“Elliott Bay is a special circumstance. They’re reconstructing the whole waterfront now,” said Munsch. “So when you’re redesigning a shoreline, you can kind of do it better if you know what you’re targeting.”

Full results of the study are published in the scientific journal Inter-Research Marine Ecology Progress Series.

Top image: U. of Washington researchers enclose an area of water next to a restored beach at Seacrest Park in Elliott Bay to collect young salmon. (Credit: Stuart Munsch / University of Washington)

0 comments