Experimental method to measure seafloor oxygen exchange tested in North Sea

Some inhabitants of the North Sea may be finding themselves a little short of breath lately. Recent evidence indicates that oxygen levels are declining in parts of the North Sea, most likely due to ocean warming and algal blooms. Quantifying just how rapidly this decline is occurring would be difficult in any part of the ocean, but the permeable, sandy sediments at the bottom of the North Sea prove particularly challenging when it comes to measuring oxygen exchange.

Scientists from the GEOMAR Helmholtz Center for Ocean Research Kiel and a coalition of European universities have tested a new measurement technique that provides an accurate glimpse of oxygen flow through the turbulent seafloor. Their findings were published in the Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans.

“Dissolved oxygen is a very important indicator of the health and function of this ecosystem in the North Sea,” said Daniel McGinnis, who at the time of the study was a senior scientist with GEOMAR. “Sandy sediment is almost like a filter in some sense.”

Sandy, permeable sediment’s capacity to filter water is enhanced by the countless organisms that live within it, converting various chemicals and impurities into energy to grow. Other larger organisms feed upon sediment dwellers, and over time that energy is transferred up the food chain to creatures as large as sharks or whales. But as the seabed becomes increasingly hypoxic, the organisms that live there produce less energy, spelling trouble for other creatures and biogeochemical processes.

Measuring the oxygen at the bottom of the sea is hard because nutrients, carbon and oxygen metabolize so quickly and unpredictably through permeable sediments. The new measurement method, known as the eddy correlation technique, takes into account previously unconsidered parameters, such as the way water flows over the sea floor and how organisms living there mix the sediment as they move through it.

The researchers tested the technique over a three and a half-week voyage aboard the research vessel Celtic Explorer. From the deck of the 65-meter ship, they dropped two landers to the floor of the North Sea. One measured the distribution of oxygen in the sediment using oxygen sensors and flow meters, while the other isolated a section of sediment for 24 hours and periodically sampled the water flowing over it to test its rate of oxygen consumption.

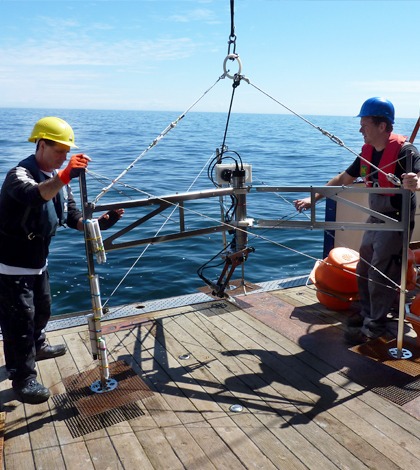

McGinnis helps deploy a lander. (Credit: Daniel McGinnis)

Together, the instruments produced 64 data points per second over several days. Combining the massive dataset with an analysis technique that was still a work in progress wasn’t easy, McGinnis said, but it was rewarding.

“It was a really neat study, and it’s such a new technique,” McGinnis said. “When you get a new dataset, it’s always a little bit challenging to work with.” In the course of working through the data, McGinnis produced a series of software tools that should help other researchers use the eddy correlation technique. They’re available for free on his website.

“The most remarkable thing I think we saw was how much the oxygen can change — the flux,” McGinnis said. “Conventionally, people aren’t used to thinking that the oxygen can change that much in a permeable system.

“When we first analyzed the data and finally got the numbers out, I almost couldn’t believe it.”

McGinnis, now an assistant professor at the University of Geneva, believes that the eddy correlation technique could greatly improve the way scientists study dissolved oxygen flow and other geochemical processes. It shows promise where other methods fail due to terrain, such as clam beds and rocky substrates. In the future, McGinnis plans to continue using the method in rivers and lakes.

“It’s a nice method because it can be applied in a lot of areas,” McGinnis said. “It doesn’t interfere with natural hydrodynamics and light regimes, it’s a really noninvasive method.”

“Hopefully people will use [the landers] as a more routine technology,” he said.

0 comments