FinPrint: Determining the Relative Abundance of Sharks and Rays using BRUVS Surveys

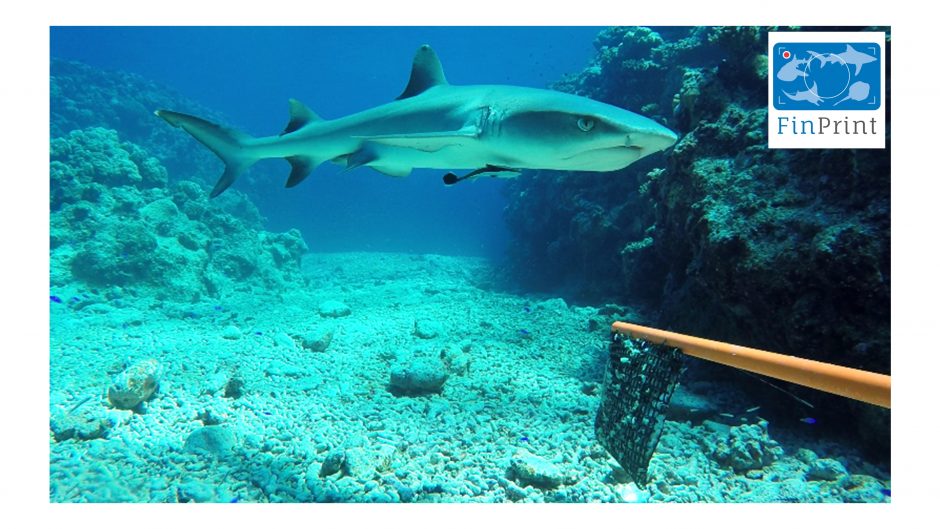

An image of a white tip shark off Scott Reef in the Timor Sea captured by the BRUVS equipment. (Credit: FinPrint)

FinPrint, the largest survey of reef sharks and rays in the world, has now completed the field work stage. Members of the scientific team are currently working on their analysis of the data, hoping to wrap this stage of the project up by year’s end. This international effort has been focused on learning more about why and how the numbers of sharks and rays are decreasing so rapidly, and the team has used BRUV surveys for monitoring throughout the project’s tenure.

Michelle Heupel, a marine ecologist and a fellow at both the Australian Institute of Marine Science and James Cook University, serves the FinPrint project as Pacific Ocean Lead Scientist.

“We’re conducting BRUVS surveys to determine the relative abundance of shark and ray species on coral reefs around the world,” explains Heupel. “The project includes sampling in a range of countries, but is also designed to include areas open to fishing and those closed to fishing. This sampling design will help inform us about the potential effects of fishing through comparison of relative abundance. We hope to see where reef sharks are still doing well, and where management or conservation intervention is needed to help maintain or recover populations.”

Conrad Speed, a quantitative marine ecologist and post-doctoral scientist from the Australian Institute of Marine Science, works as a post-doctoral scientist on the FinPrint project. The project itself is centered upon the alarming fact that at least one quarter of all shark and ray species are endangered; the remaining species are nearing threatened status (or, in some cases, not well-studied enough for conclusions to be drawn).

“Many shark populations around the world are in decline, largely due to targeted fishing and bycatch,” Dr. Speed states. “The project aims to document the global status of sharks and rays on reefs around the world to provide an up-to-date assessment of this threatened group of animals to be used by management and conservation bodies. Our project will determine what the main drivers of shark and ray abundance and diversity are, as well as identify what actions can be taken to reduce or minimize impacts on this group of animals.”

“Sharks and rays are captured and used for a variety of products including meat and fins for consumption, gill rakers and cartilage for medicine, skin for leather, etc.,” details Dr. Heupel. “This high use of these species is the main reason for their declines.”

In addition, habitat degradation and destruction is a growing problem for these species. Moreover, each insult to these animals is tough to recover from.

“Sharks and rays are particularly vulnerable to fishing due to their slow growth, late maturity, and low reproductive output,” explains Dr. Speed. “This means that once a population has been exploited through fishing, full recovery will likely be a slow process for most species.”

A BRUVS image capture of rays. (Credit: FinPrint)

BRUV surveys at work

Baited Remote Underwater Videos Stations (BRUVS) are a non-intrusive tool for observing underwater life—a tool that is becoming common for surveying fish populations. A BRUVS unit typically consists of a metal frame with video cameras and a bait container attached to it; depending on the depth of the desired survey, the frame might weight more or less. The units will generally be deployed from boats.

“The BRUVS used in this project are lightweight designs that can be hand-lowered and lifted into reef habitats,” Dr. Heupel describes. “The unit consists of a lightweight frame that includes a small, inexpensive video camera in an underwater housing and a bait arm that holds a mesh bag of minced fish in the field of view. Each unit is equipped with floating rope and a buoy for recovery of the unit.”

“Deployments are between 60 and 90 minutes and are spaced far enough apart so that the bait plume from each unit does not influence each other,” adds Dr. Speed.

Once the field campaigns are finished, team members review the video footage they’ve gathered. Their goal is to identify species and record their abundance.

“Although BRUVS have historically used bait to attract predator species, we often see individuals and species not attracted to the bait in the background of footage, such as manta rays, and some groups are now baiting BRUVS with algae to try to measure herbivorous fish abundance,” states Dr. Heupel.

However, in general, carnivores are attracted to the bait, allowing the team to identify and count target species.

“We use the maximum number of a particular species seen in the field of view at any one time as an estimate of relative abundance, which is called MaxN,” Dr. Speed explains. “We can then compare MaxN with other BRUVS from different reefs to get an idea of how abundance and diversity of one reef compares to another.”

The team worked hard to standardize the data collection process, despite the project’s huge footprint (and the many challenges associated with that).

BRUVS image capture of reef fish. (Credit: FinPrint)

“Deployments are all done during daylight hours using randomly generated locations in shallow (< 40m) depths,” Dr. Speed states. “We use oily species of fish as bait to create a bait slick to attract animals to the cameras. Weights are attached to each camera frame to provide ballast during deployment, and each unit has rope and a float attached to allow relocation after deployment. In many instances, BRUVS for this project are manually lowered and then hauled back to the surface. One of the biggest challenges with working in reef environments is where cameras are deployed around steep drop offs. This can be precarious, particularly if there are also strong currents.”

Answering questions about populations in decline

One of the goals of FinPrint is to detail which reef features are most important to retaining sharks and rays in abundance—at both local and global scales. There are several answers that the scientific team is looking to answer to achieve this goal.

“Things that influence shark and ray diversity and abundance include factors such as habitat type, whether an area is fished or protected, distance to human population, as well as other environmental factors such as water temperature and current speed,” Dr. Speed explains.

“When we analyze the data from the videos we will look to see if there are relationships between shark occurrence or abundance and reef features,” details Dr. Heupel. “For example: are sharks more likely to be present in areas of high coral cover? Relationship of shark abundance to prey abundance is one of the questions we’ll be exploring with prey density used as a factor in the analysis to see if it helps explain the patterns of shark abundance we see in the data.”

The FinPrint project operates in oceans and seas around the world, but maintains a protocol for choosing monitoring sites. The team often selects general site areas based on the presence of shallow tropical coral reef systems. In any given location, sites will be selected in two main areas: one open to fishing, and one closed to fishing—usually a protected area.

“Other factors that influence our decision making include: accessibility, existing collaborations with local scientists and managers, as well as other logistical considerations,” Dr. Speed details. “When at a study site, day to day logistics are often governed by local weather and sea-state conditions.”

Next comes the configuration of a deployment plan.

“Deployments for this project are restricted to less than 40m, are preferentially set in a variety of depths and habitat types (e.g. coral, sand, reef slope, reef lagoon) and are deployed a minimum of 500m apart,” Dr. Heupel states. “BRUV units are typically dropped in sets of 5 to 6 units in an area, soaked for an hour and then retrieved. Using this method we try to complete 4 to 5 sets per day to complete 20 or more individual samples per day.”

In action, all of the BRUV units collect data on bottom type and prey density with video footage, and some of them help collect data on temperature and current speed with attached instruments. The team measures temperature, salinity, and oxygen concentration from the surface; they also at times conduct additional belt transect fish counts to help determine prey density.

“Habitat information is extracted from BRUVS footage through software developed by the Australian Institute of Marine Science called BenthoBox,” Dr. Speed describes. “This software is an online product that allows the user to categorize benthic habitat within a grid pattern for each BRUVS deployment. Prey density can also be obtained from video footage recorded on BRUVS.”

Sharing knowledge openly, worldwide

Team members deploying equipment from the boat. (Credit: FinPrint)

One of the most notable features of the FinPrint project is that its survey data and analysis will be open source and available to all. The decision to keep everything open source both facilitates the project and furthers the spirit of the work.

“This project is the first of its kind to conduct BRUVS surveys on this type of scale,” Dr. Heupel states. “The project team and funders all recognized that while sharks are the priority in this research, we will also be recording video of a vast array of reef species. The project team doesn’t have the time, capacity, or expertise to study all of these species or consider all of the potential avenues of analysis, so it was a logical decision to make the data available for use by others. Open access to these data will increase the value of the sampling and allow a suite of questions to be answered that are beyond the scope of our work. We see this data set as a great resource for the coral reef research community.”

“The Global FinPrint Project is an initiative of Paul G. Allen Philanthropies, with the goal of providing data to better understand the ocean, drive policy making to help protect it, and encourage others to be actively involved,” Dr. Speed says. “By making the data from this research open source, it is hoped that it can be used by other scientists and managers to better understand and protect threatened species of sharks and rays.”

There is another reason to make and keep this data public: there is a huge amount of data to be analyzed.

“The team has surveyed almost 400 reefs, which is a lot of videos and data to work through,” comments Dr. Heupel. “We have accomplished the video processing through the use of students and volunteers. Their help to watch videos and count sharks has been invaluable to the progress of this project—we simply couldn’t have done it without them.”

In a project with this much video footage, creative solutions were very important, and the team came up with ways to work with volunteers successfully.

“Volunteers are often students with a particular focus on marine studies, who are trained to identify sharks and rays using software developed specifically for the project,” explains Dr. Speed. “The data are all located in a centralized database online, which links deployment information for each study site.”

In fact, this kind of transparent, international cooperation has been key to FinPrint’s success. Strong partner science agencies and scientists from all over the world have made the team and the project what it is today.

“We’ve been able to sample areas that would have been almost impossible to navigate through logistics without the on-ground support of local scientists and resource managers,” Dr. Speed points out. “Our part of the Global FinPrint team, led by Dr. Mark Meekan at the Australian Institute of Marine Science, has been focusing on the Indian Ocean over the past two years. Many of the countries our group has worked in have had their own unique logistical challenges and include sampling sites in: remote northwestern Australia, Maldives, Seychelles, Sri Lanka, India, Qatar, Saudi, Mozambique, Tanzania, Kenya, Mayotte, and South Africa.”

Dr. Heupel also credits the interest and financial support provided by the Paul G. Allen Philanthropies as a success factor for FinPrint. “Their dedication to researching and understanding the status of threatened species is at the heart of this project.”

Clearly just as important to the project: the dedication and passion of the team.

“I have always been fascinated by wildlife and in particular the marine environment,” Dr. Speed states. “Sharks are a fascinating study subject due to their elusive and often misunderstood nature and the complex roles they perform in marine ecosystems. I am thrilled to be a part of the world’s largest study on reef sharks, which will provide valuable outputs to assist in conservation and management efforts.”

0 comments