‘Fish fence’ helps endangered Sacramento River salmon

Pulsating sound, strobe lights, a bubble curtain and 1,500 live Chinook salmon: These might sound like the ingredients for a dance club gone wrong, but they’re actually the components of a recent study that could help boost survival of endangered anadromous fishes in the Sacramento River.

The Chinook salmon that run the Sacramento River to spawn in the winter have been listed as a federally endangered species since 1994. One thing that gives the fish trouble is the Sacramento River Delta’s complicated network of channels that lies between the upstream sites where young salmon hatch, and the ocean the fish must reach to live out the bulk of their lives.

If the migrating salmon stick to the main channel of the Sacramento River on their way out to sea, they have a pretty straight shot to San Francisco Bay, according to Russell Perry, a research fisheries biologist with the U.S. Geological Survey’s Columbia River Research Laboratory. But if they take a wrong turn, they’ll end up in the channels of the interior delta where they face a more complicated migration route and the intake pipes of water pumping stations.

“The channel network is much more complex, so they can basically branch off into all these smaller channels and it takes them a longer time to get to the ocean,” Perry said. “In the southern part of the delta is where the big pumping stations are located that pump water out of the delta for agriculture and domestic uses. That draws water towards the pumps, and so the fish can essentially get lost and be drawn towards the pumps instead of migrating towards the ocean.”

In an effort to keep the fish on the right track, the California Department of Water Resources installed and tested a fish-repelling fence — consisting of sound waves, flashing lights and a wall of air bubbles — at one of the two channels that branch off from the main stem of the Sacramento River where misguided salmon can enter the lower delta.

Fish-diverting sounds and lights, known as behavioral technologies, aren’t new. But they also aren’t a sure thing. For example, a test of strobe lights at Cowlitz Falls Dam in Washington had the opposite of its intended effect, appearing to increase the number of juvenile steelhead pulled into turbine intakes.

“Behavioral technologies have met with mixed success in past years,” Perry said. “So they haven’t really been implemented as a standard tool for either attracting or repelling fish away from different locations.”

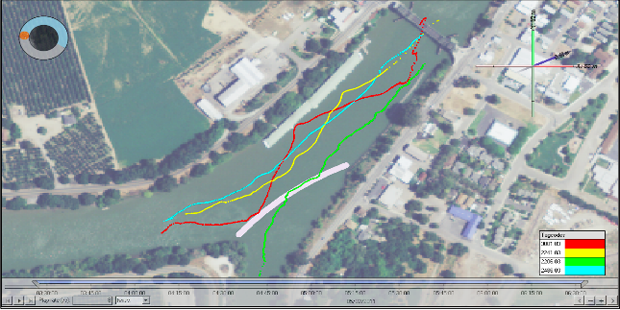

For this study, crews installed a 190-meter fish fence in the Sacramento River where Georgiana Slough forks off from the main stream and flows into the inner delta. Unlike the technology installed at Cowlitz Falls Dam, which consisted only of flashing lights, this installation combined lights, sound and a bubble curtain. Upstream of the curtain, researchers released 1,500 juvenile Chinook salmon (from the late-fall run population, not the endangered or threatened groups) obtained from the Coleman National Fish Hatchery. The fish carried surgically implanted acoustic transmitters that produced locating signals picked up by 20 receivers installed around the fence site.

The data show that the fence served its purpose. When it was turned on, around 7 percent of tagged fish took a left turn at Georgiana Slough and headed toward the interior delta. But when the fence was off, that jumped to around 22 percent.

Colored lines show the tracks of tagged fish; the green line shows a fish turning left down Georgiana Slough (Credit: California Department of Water Resources)

The combination of several fish-spooking technologies likely contributed to this study’s success compared with past efforts to guide fish.

“I think that’s pretty novel, and there haven’t been a lot of applications of that in the past,” Perry said. “There have been some small scale experiments that have been successful, which is what spurred this larger scale experiment.”

The study appears in the journal River Research and Applications.

Top image: A pair of Chinook salmon (Credit: USFWS, via Wikimedia Commons)

0 comments