Fisheries Management Drives Fish Populations Recovery

A fishing vessel returns from a trip off the coast of California. Fisheries that are intensively managed are seeing a return to sustainable populations of targeted fish. Credit: Mike Baird, Flickr)

You might be surprised to hear good news about the world’s oceans. The dominant narrative for years has been that the oceans’ sea life populations are on the brink of collapse.

But, according to research Ray Hilborn published in January in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, the ocean’s fisheries are bouncing back, provided that they’re well managed.

“The bottom line is that if fisheries are managed they are sustainable,” Hilborn, a professor at the University of Washington’s school of aquatic and fisheries sciences, told Environmental Monitor.

New evidence of recovery

After two decades of recovering fish populations, many of the world’s fisheries are stable or recovering, Hilborn’s research shows. Scientific surveys of fish abundance can show which populations have biomass for maximum sustainable yield: the amount of fish that allows for the most fish to be removed while sustaining a healthy population.

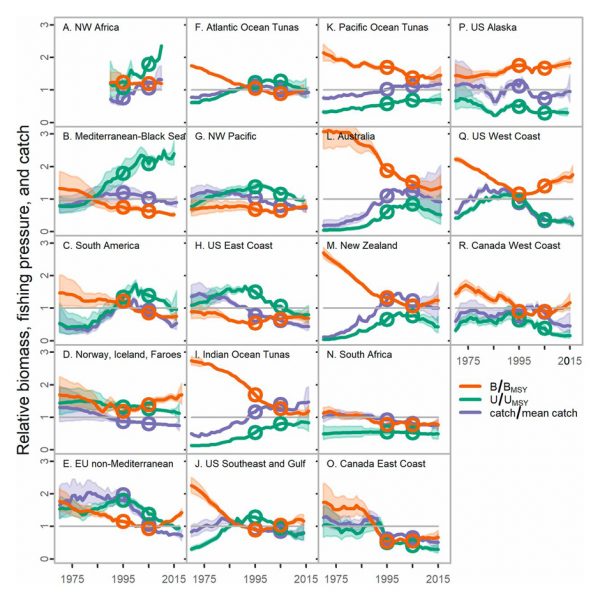

The necessary data is available for 50% of the fisheries around the world. On average, those fisheries had biomass greater than and fishing pressure lower than what is expected to produce maximum sustainable yield. Forty-seven percent of fisheries actually had higher biomass and lower fishing pressure than maximum sustainable yield standards. A further 19% had low biomass, but fishing pressure was low enough to expect recovery. But, 10% had low biomass and high fishing pressure, meaning fish populations are likely to continue declining if fishing pressure remains high.

Graphs showing the relationship between biomass as a portion of biomass at maximum sustainable yield (orange), fishing pressure as a portion of fishing pressure at maximum sustainable yield (green), and catch as a portion of mean catch (purple). Intensively managed fisheries are more likely to be at or approaching sustainable levels. (Credit: Reproduced with permission from the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA)

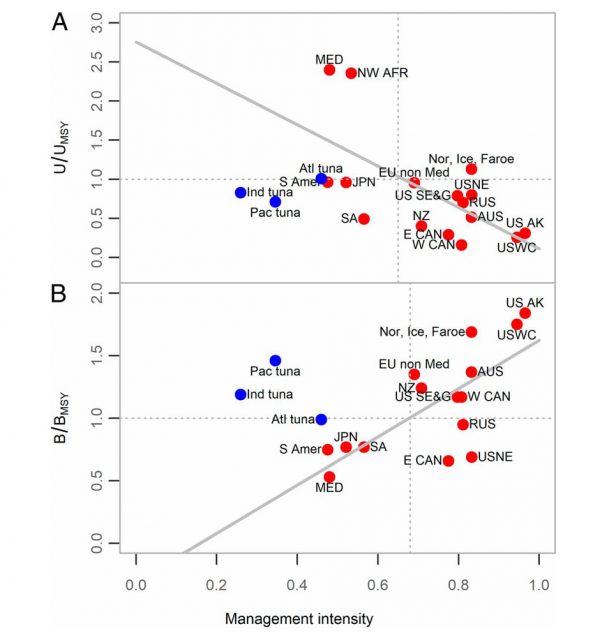

The research also shows a strong correlation between the recovering fisheries and the intensity with which they are managed.

The intensity of fisheries management (as measured by previous research) takes into account the levels of research, regulation and enforcement as well as socioeconomic data.

Intensity, catch and biomass data don’t exist for every part of the world. While the necessary data to make these analyses exist for North America, parts of South America, Europe, northwestern and southern Africa, Australia and New Zealand and the Mediterranean Sea, gaps still exist.

The biggest gaps are Southeast Asia fisheries, including China, where little information on abundance or catch exists. Information is also lacking from eastern and central Africa, the Middle East and Central America.

Two decades of fisheries recovery

This new evidence of recovering fisheries comes after 25 years of a shifting approach to how nations manage their fisheries. In 1982, the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea helped usher in this new fisheries management paradigm. It adopted measures that said nations managing fisheries “should cooperate to ensure conservation and promote the objective of the optimum utilization of fisheries resources.”

Beginning in 1995, when portions of the 1982 agreement went into effect, the amount of fish caught began to fall and overall biomass of targeted fish began to rebound as fisheries were managed for maximum sustainable yield.

Previous research showed that 10 years is enough time for most overfished stocks to recover, though the actual time required varies. The extent to which a fish stock has been overfished has its own impact.

Fish stocks are considered overfished at different levels depending on the regulating authority. Some consider stocks overfished when they get to half the biomass necessary for maximum sustainable yield. Others set the threshold at 80%. Stocks with less than 20% of their biomass that produces maximum sustainable yield are considered collapsed and take longer to recover.

Fish stocks around the world are not all on the same path to recovery, according to this research. Biomass in the Mediterranean and Black Seas are trending down and already below the biomass that would produce maximum sustainable yield. On the whole, South American fisheries fall short of biomass targets, but fishing pressure is decreasing, allowing for the possibility of recovery.

Fisheries currently at or above biomass required for maximum sustainable yield include most North American, European Union and South African fisheries.

But, for a significant portion of the world’s fisheries, the necessary data isn’t available or isn’t being translated into best management practices.

As fisheries management intensifies, fisheries rebound to sustainable levels. (Blue dots indicate tuna fisheries. (Credit: Reproduced with permission from the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA)

Expanding effective fisheries management

Stock assessments aren’t available for a variety of reasons, Hilborn said. Sometimes the sticking point is a governmental choice. Sometimes countries lack the scientific expertise to evaluate the data or turn it into management practices.

But, collaboration between scientists means that trends in biomass could soon be understood where they currently are not.

“We’re doing a lot of work with countries like China now to try to understand better where the stocks are going,” Hilborn said.

The University of Washington recently hosted Chinese fisheries scientists for training in turning fisheries data into fisheries management practices, until the Covid-19 pandemic ended the exchange.

The concerns are different elsewhere.

“The big issue that you encounter in fisheries management is the tradeoff between protecting biodiversity and producing food. Different countries have different priorities,” Hilborn said. Share on XRegardless of the reason for specific gaps in stock assessments and fisheries management around the world, as they are filled in, it’s possible fish populations will rebound as they have in other, intensively managed areas.

0 comments