Florida’s War Against Toxic Algal Blooms

Dr. Lapointe working on the water. (Credit: Dr. Lapointe, https://hboihablab.weebly.com/gallery.html)

If you follow the news, you’ve seen large-scale harmful algal blooms (HABs) in Florida this summer. They are present in Lake Okeechobee and the Caloosahatchee (CE) and St. Lucie (SLE) estuaries and rivers, and they’re wreaking havoc on summer recreation and even the health of local residents.

Dr. Brian Lapointe of Florida Atlantic University’s Harbor Branch has been researching HABs for decades. The Lapointe HAB Lab site features his ongoing work, and Dr. Lapointe took the time to speak with EM about the HABs and his work studying them.

The “seeds” for these blooms were sown long before now, with the heavy rainfall that accompanied extreme weather events of the past.

“This particular toxic green microcystin that’s affecting Lake Okeechobee and the Caloosahatchee in St. Lucie really began in 2005, which was a very active hurricane year,” details Dr. Lapointe. “It’s those years that really stress the water systems in Florida. So we get a lot of rainfall, a lot of runoff, and that’s kind of the hammer that brings the nutrients from the groundwater into surface waters like Lake Okeechobee.”

Rapid growth, unchecked pollution

Reading much of the news coverage of the 2018 algal blooms, you might be tempted to believe that the growing population of the state isn’t much of a factor and that industrial and agricultural pollution are the main driving forces behind the HABs in the area. However, Dr. Lapointe’s research reveals that development and population growth are playing a crucial role in the pollution that feeds the HABs.

Nutrient pollution in marina on Caloosahatchee River near Cape Coral, 2005 (Credit: By John Cassani [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons)

Why is Lapointe so certain that agriculture and industry aren’t the real problems?

“We take samples of the water and algae and we analyze it for nitrogen isotopes to identify the source of the nitrogen, whether it’s sewage or fertilizers or whatever,” Dr. Lapointe describes. “We use not only the nitrogen isotopes but also human tracers like sucralose that tell us it’s not from the sugar plantation.”

Dr. Lapointe refers to case studies in Florida, particularly in Tampa Bay, that prove the utility of taking a scientific approach to cleaning up sewage in urbanizing areas.

“You can actually grow the population without these adverse consequences,” comments Dr. Lapointe. “They used sound science and nitrogen removal from sewage to actually grow the population, and in the case of Tampa, millions of people came over recent decades while the Bay got better and better. Because they understood the science of the problem.”

Finding a scientific solution to a political problem

The HABs are nothing new in Florida—but they are a growing problem. This summer, Florida Governor Rick Scott authorized emergency measures that will be taken to counter the blooms. According to Dr. Lapointe, whether or not those emergency measures will be effective will depend largely upon whether they will be based on scientific evidence.

“We have a number of environmental groups in Florida, and they blame big sugar, these farms south of Lake Okeechobee, for this problem,” remarks Dr. Lapointe. “But it’s really not their fault. The water and the nutrients are coming in from the north of the lake, the Kissimmee River. What’s at the top of the Kissimmee River Basin near Orlando? Disney World. So, you know what’s coming down.”

Dr. Lapointe in the field in the Florida Springs area. (Credit: Dr. Lapointe, https://hboihablab.weebly.com/gallery.html)

The area north of the lake, surrounding Orlando, is one of the fastest growing areas in Florida—a state that’s already one of the fastest growing in the US.

“It resembles L.A. to me, it’s growing so fast,” adds Dr. Lapointe. “And like I said there are a lot of septic tanks there.”

During the many extreme weather and even during “normal” but heavy rainfall events, a rush of water enters the Kissimmee River. That river was “channelized” or straightened by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) so it could drain more quickly into Lake Okeechobee—but this also destroyed the river’s natural filtration process. The USACE is now restoring part of the Kissimmee to provide more dynamic storage, but because 95 percent of the nutrient-rich water causing the blue-green algal blooms in Lake Okeechobee is coming from north of the lake, restoring the river alone won’t solve the problem.

“What they’re proposing as the solution is building a reservoir down south of the lake,” explains Dr. Lapointe. “When we get these major rain events, the lake rises too fast, and the Army Corps has to discharge water from the lake either to the Caloosahatchee which goes down to Fort Myers or to the St. Lucie River that goes down to Stuart, Florida on the East Coast. Building the southern reservoir will send the water south towards the Everglades in Florida Bay, essentially moving the problem somewhere else, rather than dealing with the source of the problem which is north of the lake.”

In other words, source reduction is really what works most effectively—unless you get lucky.

“I think we’re at a critical time here in the state of Florida, where to really get on top of this problem we really have to use sound science and not politics as usual which unfortunately has gotten us to where we are today,” adds Dr. Lapointe.

Preparing for Florida’s future

2018 may be a year of relative respite in terms of extreme weather events, but that isn’t going to make a long-term difference for the state’s HAB problem.

“We might be spared [from major hurricanes] this year, but I think in the long run we’re likely to see more of these tropical storms in the future, and stronger storms,” explains Dr. Lapointe. “That is the prediction with climate change, that we’re going to actually see increased frequency and intensity of these rain events which is like I said, the hammer.”

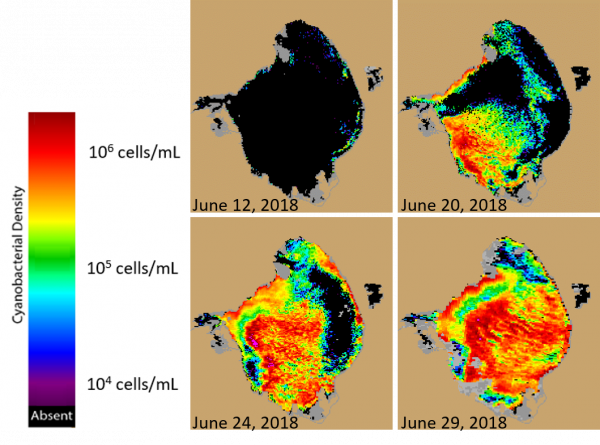

June 2018 NOAA satellite images depict the development of a bloom in Lake Okeechobee. (Credit: NOAA)

According to Dr. Lapointe, the increase in extreme rain events alone in the years to come is going to increase nitrogen loading in the water by 20 percent. Mitigating that 20 percent will require a reduction of the human nitrogen footprint by about 30 percent.

“We have a framework, the total maximum daily load (TMDL) amounts that have been developed for different basins around Florida,” remarks Dr. Lapointe. “To achieve those goals, we have to begin to reduce nitrogen in each of those basins for which there’s a TMDL, and we’re doing that through the basin management action plan (BMAP).”

The way to do this is to sever the head of the septic snake.

“I already explained the problem with septic tanks; we have too many of them in Florida,” states Dr. Lapointe. “It’s ridiculous, really. One of the most significant things we could do to significantly reduce the nitrogen loads in the basins north of Lake Okeechobee and along the Caloosahatchee and the St. Lucie, would be to get rid of these septic tanks and implement septic sewer programs.”

Septic sewer programs replace septic systems with municipal sewers and divert sewage to treatment plants. Treatment reduces nitrogen in the effluent from an average of 65 milligrams per liter to one milligram per liter.

“Now that tells you what the problem is, doesn’t it?” Dr. Lapointe describes. “It’s a major source of the nitrogen fueling the algae blooms we are seeing, and it’s out of sight, out of mind, because people have septic tanks and they’re permitted by the state of Florida. It’s all underground, they can’t see it. And they are having a hard time believing that their septic tank is part of this problem. But that’s what the research is showing, and not just mine. And the more you look at it, the more dire the situation is.”

Cost may be another reason some Floridians resist the idea of septic pollution as a driving force behind HABs.

“Don’t forget, it’s not free,” remarks Dr. Lapointe. “We’re going to have to have to get our checkbooks out and actually pay to live in paradise. Paradise ain’t cheap. If you live here sustainably, you just have to pay for having a clean lake Okeechobee. All of us are going to have to pay. And you know human nature. A lot of people don’t want to pay.”

Blue-green algae bloom on Lake Okeechobee, 2016. (Credit: By NASA Earth Observatory images by Joshua Stevens, using Landsat data from the U.S. Geological Survey. Caption by Kathryn Hansen. [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons.)

“We won’t even be able to live here,” warns Dr. Lapointe. “People have had to evacuate their homes over there in Cape Coral where these blooms are. Imagine that: living on a canal like that, you’ve got your boat there. Life is good. And then this algae shows up, and you can’t breathe. There are toxic fumes.”

Lapointe adds, “The idea of using politics to try to solve environmental problems has now backfired here in Florida, and it’s not a pretty sight.”

While some people may be starting to understand why environmental regulations exist and how to generate better results over the long run, there is also a lot of free-floating frustration about the process—and time is running out.

“You just look at the basic facts, and to me, it seems kind of obvious even without my science that this is more related to human population growth,” remarks Lapointe. “There’s just huge denial there. No one wants to believe it. It’s interesting.”

Top image: Dr. Lapointe working on the water. (Credit: Dr. Lapointe, https://hboihablab.weebly.com/gallery.html)

0 comments