From Alkalinity to Zebra Mussels: Murray State’s Hancock Biological Station Reveals Trends Via Long-Term and Real-Time Environmental Monitoring

Hancock Biological Station’s floating laboratory used in the monitoring program. (Credit: David White)

“Western Kentucky is special because large reservoirs are greatly understudied,” says David White, Professor Emeritus of Biology at Murray State in Kentucky and retired Director of Hancock Biological Station. The station is a member of the Organization of Biological Field Stations (OBFS), the Global Lakes Ecological Observatory Network (GLEON) and the Association of Ecological Research Centers (AERC).

The area has one of the largest densities of major rivers and reservoirs in the world. Hancock Biological Field Station sits on Kentucky Lake, the largest reservoir in the U.S. east of the Mississippi River. The area is where the Cumberland River, Tennessee River, Ohio River and Mississippi River converge. Also nearby are the cypress swamps of Reelfoot Lake and Murphy’s Pond.

In his 30 years at Hancock Biological Station, White has overseen both real-time and long-term environmental monitoring programs. “Our long-term monitoring efforts began 30 years ago when we were first recognized as a ‘Center of Excellence’ by the state of Kentucky. Our goal was to understand physicochemical and biological patterns and how the reservoir performs year round. We are only 15 minutes from the Murray State campus, giving easy access to Kentucky Lake for students and faculty,” White says.

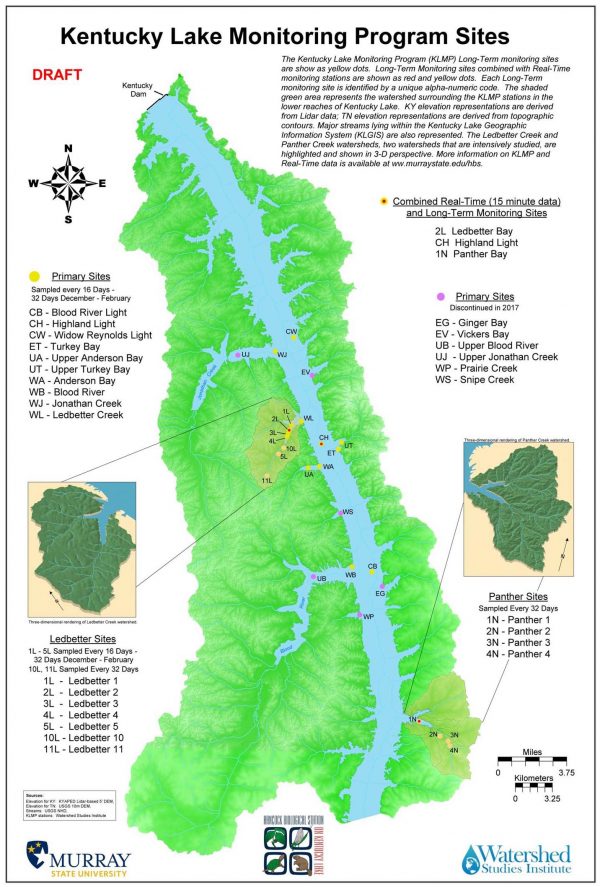

The Kentucky Lake long-term monitoring program consists of 14 environmental monitoring sites with some located mid-channel in several of the bays and in two, small, paired watersheds. The watersheds include one in a forested area and one in a rural area.

Monitoring sites along Kentucky Lake (Credits: Elevation for KY: KYAPED Lidarbased 5′ DEM, Elevation for TN: USGS 10m DEM, Streams: USGS NHD, KLMP stations: Watershed Studies Institute and Murray State University)

“We use 16 days as our monitoring interval because it corresponds with LANDSAT flyovers, allowing us to coordinate our research data from the ground with satellite data,” White explains. The Hancock Biological Station environmental sampling crew goes to all the monitoring station sites on the same day, taking a suite of chemical, physical and biological data, including temperature profiles and conductivity, nitrogen, phosphate, silica, pH, chloride, chlorophyll and turbidity measurements. C14 primary productivity at each site. Secchi depth is used to measure water transparency. Originally using Hydrolab equipment, Hancock switched to YSI in the late 1990s and presently uses YSI 6600 data sondes. Each sampling date is called a “cruise.” Cruise 600 will occur in March 2019. To date, more than 200 students and faculty have participated in one or more cruises. Long-term data are available to scientists interested in collaborative research.

“We’re the last reservoir and largest reservoir in the Tennessee River System. Because of that, we experience the sum of what occurs in the entire watershed,” says White. When asked about trends he’s observed in the data for Hancock Biological Station over 30 years, White reflects, “We have seen some very interesting data trends. For example, we have seen a temperature increase of nearly two degrees Celsius over time, which is very significant. We’ve seen Secchi depths going up, nitrogen and phosphorus staying about the same, pH heading towards more alkaline. We’ve also seen a significant decrease in sulfate from about 30 mg/L down to 10 mg/L due to the installation of scrubbers in power plants that have been removing atmospheric sulfate.” Data gathering at Hancock will continue into the foreseeable future.

Our fixed real-time monitoring site located just off the main channel of Kentucky Lake. YSI 6600 sondes are set at 1 m from the water surface and 1 m off the bottom. (Credit: David White)

“Changes in Kentucky Lake also include the arrival of invasive species,” White explains. In the past decade, Kentucky Lake has seen the invasion of silver carp. In the past year, invasive zebra mussels have also arrived. “They’re both planktivores,” says White. “There’s a delicate balance at work here with phytoplankton, zooplankton and the chemical environment of the water. We are pretty low in nutrients. Kentucky Lake is not a hugely productive system. That being said, if the balance of nutrients and chemicals in the lake change even slightly, you can start seeing significant differences, such as an increase in clarity and decreases in zooplankton and phytoplankton abundances. We’ve observed a rise in zebra mussels once the calcium level got above 21 or 22 ppm in the lake. Above that level, zebra mussels can survive and reproduce. These are trends we have seen only because we have long-term monitoring data.”

Real-time monitoring at Hancock Biological Station started in 2005. Hancock now has two mobile buoy platforms and one fixed system that return data every 15 minutes using cell phones and radio. Funding for the real-time monitoring has been through National Science Foundation grants. Each site is equipped with data sondes, weather stations, PAR sensors, etc. “Initially we used NexSens technology for real-time data gathering and now are using Campbell Technology. We are upgrading to YSI EXO-2 sondes soon,” says White. “We just placed an order.” Both nitrate and phosphate sensors have been added recently.

While researchers at Hancock use their real-time data frequently, it is popular with the general public as well. “Fishermen use our fixed site temperature and oxygen data a lot. We get thousands of hits because of them,” says White. “We’ve been providing them with information for 13 years now, and that helps them fish more productively.” Real-time data are available on the website: www.murraystate.edu/hbs. The data generated by the two mobile buoys are not currently available to the public, but they are available for collaborative research purposes.

Graduate students launching one of our two YSI Pieces monitoring buoys (Credit: David White)

“Gathering good data comes with challenges,” White reflects. “Sometimes probes stop working, especially pH probes. Sensors need to be cleaned, replaced or recalibrated. We need to be diligent at all times so the flow of data is interrupted as little as possible.”

A current research question of interest is: what conditions must be in place for a blue-green algal bloom to occur? “We’ve added nitrogen and phosphorus real-time sensors so we can get a better handle on the answer to that question,” says White.

Work at Hancock Biological Station continues to be richly rewarding for the scientists who work there. “Being on Kentucky Lake is a great experience,” White says fondly. “It’s also very gratifying to see that our long-term data are picking up trends seen by other scientists.” The Kentucky Lake location has had other benefits as well. “We were in the zone of totality for the solar eclipse,” White recalls. “It was exciting to watch the real-time buoy data catch the changes in PAR that happened during the eclipse.”

Originally a pre-med student, White worked on a grant at DePauw University that led him to explore sediment pollution in streams and focus on aquatic biology. He earned both a bachelor’s and a master’s degree in Zoology at DePauw and then a PhD in Biology at Louisville. “I’ve been able to do fascinating research here that involves undergraduate and graduate students and collaborations around the world,” says White of his time at Hancock Biological Station.

Top image: Hancock Biological Station’s floating laboratory used in the monitoring program. (Credit: David White)

0 comments