From Florida to the World: How a Smithsonian Research Station is Bridging Gaps in Marine Biology

In the early 2000s, along the coast of northern California, where the redwoods dominate the forests, and the Pacific Ocean shapes shorelines, a Humboldt University undergraduate student took the first steps into a lifelong love of marine biology.

Dean Janiak accepted an invitation to help a graduate student with fieldwork in rocky coastal tide pools, and so began a journey that led him from California to Connecticut to Florida and eventually to the world, where he has facilitated research in communities across the globe.

While finishing up his masters of Oceanography from the University of Connecticut, Janiak continued researching fouling communities–marine life that live on hard, often artificial surfaces such as docks–at the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center.

After his supervisor retired, he decided to take his research to the Florida coast, specifically to the newly created Smithsonian MarineGEO Station. As part of a larger network, the program brings together many branches within the Smithsonian to promote coastal climate change research.

Janiak deploying a YSI EXO2 at the dock outside of the MarineGEO station. (Credit: Dean Janiak)

It was in the Sunshine State, where marine research is as prevalent as the oceans, lagoons, and rivers that define its landscape, that Janiak began to realize the global impact he and his research projects could have. Now a biologist and lead researcher at the station, Janiak and his colleagues study marine biodiversity and coastal climate change, but approach it differently than most.

“No matter how big or how small a plant or animal is, it’s having some sort of function in a system,” Janiak says. “[…] so what MarineGEO does is we’re studying this on a global scale.”

Located next to the Indian River Lagoon along the Atlantic coast, where the ocean, inland water bodies, and human-dominated landscapes intertwine, this area may seem primed for complex ecological experiments and research. While Janiak spends time monitoring fouling communities in the lagoon and using a YSI ProSolo handheld dissolved oxygen meter to track water quality, the work at MarineGEO extends well beyond Florida’s waters.

Janiak explains that while science is often conducted on local scales, it may not always be the best method for a rapidly changing natural world. A practiced scientific communicator, he likens this train of thought to how we often only understand what’s right in front of us without accounting for the full picture.

“You know what’s in your backyard. You know the plants there, you know the animals there, you know how it changes from season to season, but you don’t know what’s in my backyard,” Janiak explains.

“So that’s how science has been done, classically, for as long as it has been done. We know our [own] backyards really, really well, but we don’t know how our backyards are connected or how they differ,” he continues.

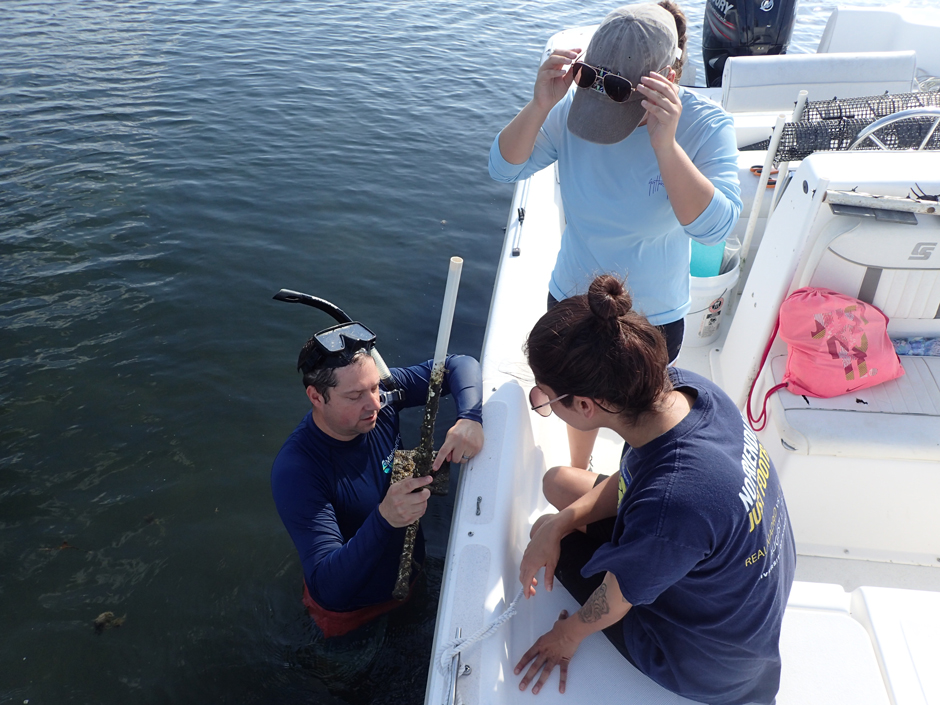

Janiak shows interns different species in their annual MarineGEO monitoring of fouling communities. (Credit: Dean Janiak)

Marine Research on a Global Scale

One way that MarineGEO is working to disseminate crucial ecological information on broader scales is by creating standard protocols. From how seagrass is changing to researching the complexity of coral reefs to investigating the impact of artificial habitat on fouling communities, it is believed that by standardizing these protocols, researchers across the world can identify common stressors to ecological issues.

Rather than hyper-focusing on local issues, Janiak and his colleagues hope that the knowledge of how oceans, coastlines and marine ecosystems are changing can be more easily understood on global and regional scales. And they achieve this by facilitating research projects from Florida to coastlines around the world.

The difference between these research projects, however, and the more common local research is their simplicity. Remote communities or those without adequate funding don’t have the resources to conduct complex research.

So, MarineGEO steps in by not only coordinating projects with these communities but also providing lessons on proper research techniques and taxonomic identification as well as taking on the heavy lifting in terms of data analysis.

“If you’re doing it locally, it’s going to be a lot more complicated,” Janiak says. “And so by scaling up we can really minimize the amount of work we actually have to do, which is really nice. So these experiments are really impactful at [understanding fundamental mechanisms].”

Janiak measuring dissolved oxygen off the side of the dock outside of the MarineGEO station. (Credit: Dean Janiak)

From Ocean Trash Movement to Fouling Predation Patterns

MarineGEO has coordinated a project where participants simply identify and pick up trash on the beach. The difference is that this occurred at hundreds of sites across the world. After participants determine the characteristics such as material, ability to float, and presence or absence of animals attached, MarineGEO takes on the analysis.

Using ocean current data, MarineGEO modeled the paths this trash has taken, using it to find where it originated from, what types of trash travel farthest, and if they are carrying invasive species. While such projects use citizen scientists, MarineGEO also works with other research institutions and universities.

For example, Janiak recently helped students at the University of the Virgin Islands determine their graduate project. After sharing his knowledge and the resources that MarineGEO can provide, the students decided to focus on monitoring fouling communities. Janiak sees this as a win-win, as he guides these students in their academic endeavors while MarineGEO gains more partners and another monitoring site.

Some of their large-scale projects aim to test some of the most prevalent theories in ecology, all with minimal logistical and technical difficulties. Once again connecting back to his roots, Janiak is currently wrapping up a project observing predator and fouling interactions. One of the largest he has taken on, he pulled it off using the same idea of simple methods across great distances.

Although he had dozens of research sites up and down the East and West Coast, the work he coordinated with partners involved caging a fouling community, protecting it from predation, and observing how it changed in response. A simple experiment led to profound results, which will be shared in a scientific paper coming out later this year.

“We looked at how as you move from the poles down to the equator, predation becomes more intense, and so it changes the way the communities look more rapidly,” Janiak says. “[…] but it got into Science. And that might be the only time I’ll ever get my name in a Science paper because it’s so hard and it’s so prestigious, but it’s just something simple that we did in collaboration with a lot of people, and I think it shows the power of network science.”

Fish congregating under a dock. which provides habitat for the fish and fouling communities on the poles. (Credit: Dean Janiak)

Monitoring in their Own Backyard

Ultimately, MarineGEO staff take the knowledge from their global projects to continue protecting their backyard, the Indian Rover Lagoon. As they understand the world’s backyards, they use it to help improve monitoring in lagoon habitats.

Janiak and the team at MarineGEO use a YSI EXO2 sonde, stationary at their dock, to measure DO, salinity, temp, pH, turbidity, and chlorophyll every six minutes. Their goal is to track annual changes in water quality with changes in important species, from seagrass to oyster reefs to mangroves and manatees, helping to inform state legislature through their work.

Janiak finds himself at local meetings, using the communications skills he has gained from participating in global projects to share MarineGEO’s work with Florida residents. Their data on the health of some of Florida’s most precious and unique ecosystems continues to drive marine biology and conservation.

Yet behind it all is the knowledge that MarineGEO is just one part of a much larger picture, a network of interconnected researchers, students, and citizen scientists working together to push science forward. While challenges from funding, legislative restrictions, and engagement subsist, the team at MarineGEO sees the ultimate value in their work.

“We have knowledge from all over, and it could be relatively helpful, if you want to restore a local area, [to know] how those techniques work in different parts of the world,” Janiak explains. “I think having a scope as large as we do, that helps predict patterns and change.”

Janiak and his team monitor oyster reefs in the Indian River Lagoon. (Credit: Dean Janiak)

Sean Craig

March 2, 2025 at 4:54 pm

Nice story about an important project-way to go Dean Janiak!

-Sean Craig