Getting the Lead Out of Childcare Centers

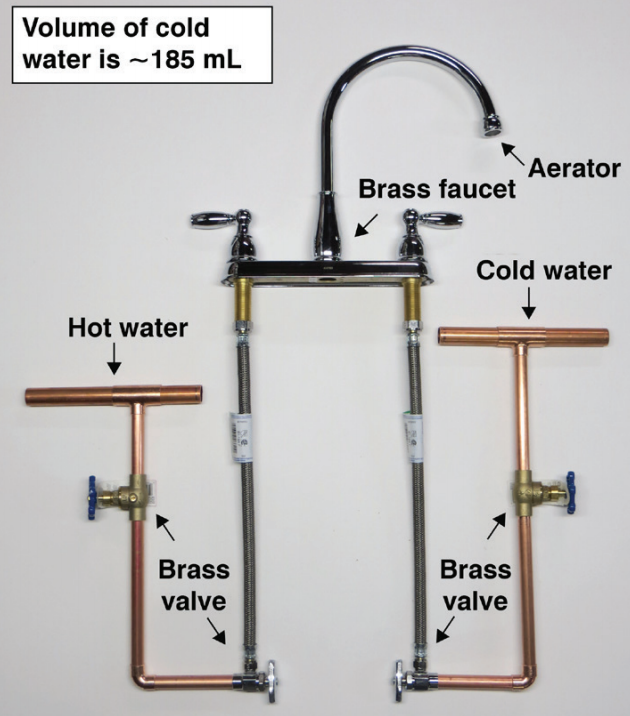

Typical fixture and associated plumbing. (Credit: EDF, https://www.edf.org/sites/default/files/documents/edf_child_care_report-062518.pdf.)

A recent report from the Environmental Defense Fund (EDF) reveals that there is lead present in drinking water among childcare centers in different parts of the country. The report clarifies where problems are appearing, and sets forth new, more stringent recommendations for standards.

Testing water faucet by faucet

Lead is unsafe in drinking water, at any level. It is especially risky for children because lead exposure can impair normal brain development, leading to problems learning and behavioral issues.

Despite understanding the risks that lead poses to children, there remains what the EDF report calls “a toxic legacy of lead” in the US. Of course emergencies in places like Flint, Michigan highlight the problem, but in reality, it is much more widespread, and, in some sense, mundane—a problem most commonly related to such non-dazzling topics as aging infrastructure, materials in plumbing fixtures, and occasionally water treatment standards.

“Children in child care facilities are younger; they’re more vulnerable to lead because their brains are still developing,” explains EDF researcher Lindsay McCormick, who authored the report. “Children under the age of six stand to lose the most from lead exposure, and formula-reliant infants experience the most risk because their formula is typically mixed with drinking water.”

All of this means that child care facilities should be at the top of the list when it comes to reducing lead exposure, since so many young children spend so much of their days in these facilities. Paradoxically, however, these facilities are falling through the cracks, and young children are falling with them.

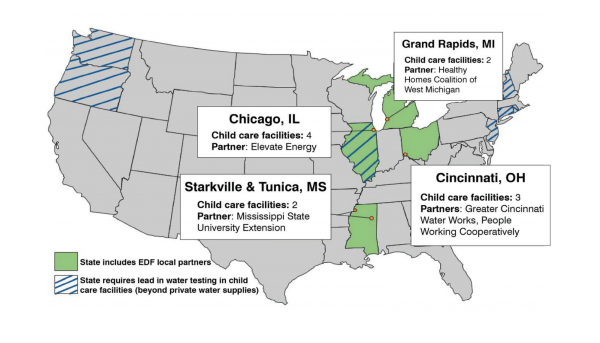

Lead in water at child care facilities: Existing requirements and EDF partners. (Credit: EDF, https://www.edf.org/sites/default/files/documents/edf_child_care_report-062518.pdf.)

The voluntary Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) guidance for lead, “3Ts for Reducing Lead in Drinking Water,” suffers from significant gaps in the child care setting. Perhaps the most notable of these is its action level for lead contamination, which stands at an outdated 20 parts per billion (ppb). Furthermore, few states require testing for lead in water at child care facilities.

This overall problem and urgent need prompted the EDF’s study.

“One thing we’re doing is urging the EPA to update their voluntary guidance,” remarks McCormick. “We have recommendations for water utilities, public health departments, and state regulatory agencies in the report. We’re hoping we can help them look at the problem through the lens of each key stakeholder, and see which lessons they can pull from our project.”

The study and its results

Working with local agencies and other partners, the EDF team collected more than 1,500 water samples from 294 fixtures and 14 water heaters. 172 of these were hot water samples. The samples were analyzed at a certified laboratory, and 65 percent of them were also analyzed with a portable meter. Read the full protocols here.

Both commercial buildings and homes converted into childcare facilities were tested. The facilities tested in the study serve more than 1,000 children in total, who are primarily from low-income families. The facilities tested are located in Illinois, Mississippi, Ohio, and Michigan.

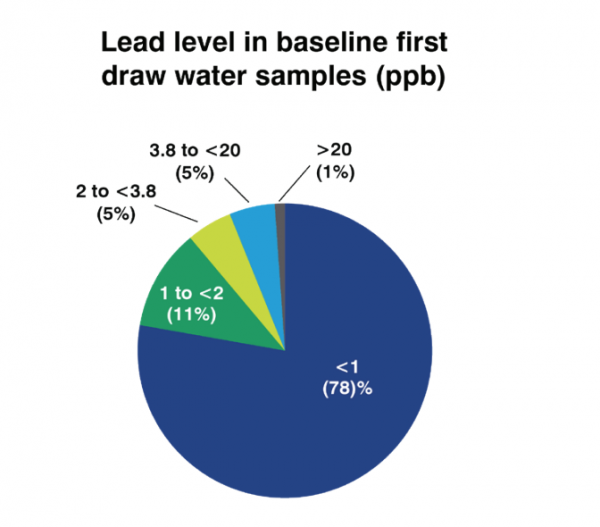

The team found that most samples contained lead at very low levels. In fact, more than three out of four samples collected had non-detectable lead levels (<1 ppb). However, of the 11 child care facilities that were tested, seven had at least one sample above the EDF action level of 3.8 ppb (or >2 ppb in Chicago).

Lead level in baseline first draw water samples. (Credit: EDF, https://www.edf.org/sites/default/files/documents/edf_child_care_report-062518.pdf.)

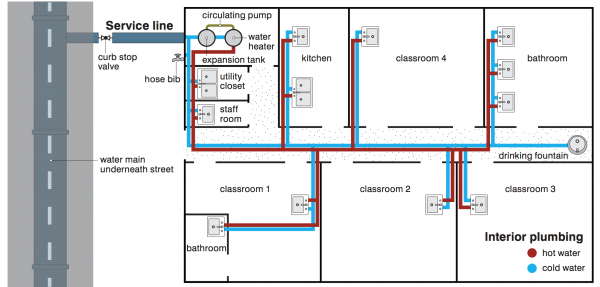

The team next identified and removed sources of lead in drinking water that posed higher levels of risk. Brass fixtures and lead service lines, for example, posed a more significant risk of lead exposure in several facilities. The team replaced two lead service lines that connected the water mains to the building—one in Chicago, one in a Cincinnati. They also removed and replaced 26 fixtures which showed lead concentrations above the EDF action level for lead.

The team also showed people in the facilities how to reduce lead concentrations in places where it was present in low amounts. Flushing fixtures by running the water for five to 30 seconds reduced lead levels in many cases—the five-second flush is effective, the 30-second flush, even more so.

The team also recommends more study of the issue of removing and rinsing the aerator screens at the end of faucets, which is important to do but may actually cause lead levels to rise. The researchers also drained and flushed 10 water heaters to get rid of any lead particulate that could have built up inside them. The team found that water heaters can act as traps for lead, retaining this particulate matter in their tanks, and called for more investigation of the matter.

When the team found lead levels that were high at the outset of testing, they often replaced the fixtures. This was often effective, but they were not always able to reduce lead levels below the action threshold. This is in part due to the NSF International standards for new brass fixtures, which are permitted to leach up to 5 ppb of lead into the water—well above the 3.8 ppb EDF action level.

One other disturbing finding from the study was that the portable lead meters the team used in the field—which any home or local user might employ—were less accurate than the laboratory analyses, underestimating lead levels.

Getting the lead out

The EDF team make a number of recommendations in the report, directed at various stakeholders. They’ve framed their guidance as a significant opportunity each stakeholder has to reduce lead exposure for vulnerable children in childcare facilities.

Water distribution system at typical center-based child care facility. (Credit: EDF, https://www.edf.org/sites/default/files/documents/edf_child_care_report-062518.pdf.)

For child care centers, the recommendation is to inspect service lines, both visually and by reviewing historical records, and to replace them if they are lead. The EDF also advocated for mandatory testing in childcare facilities, so that sources of lead can be identified and dealt with appropriately.

The EDF also recommends flushing fixtures before collecting and using the water—and McCormick herself has added this into her routine.

“I personally now will run my water for a few seconds beforehand,” states McCormick. “We found that flushing for just five seconds significantly reduced the levels of lead. Part of it is just flushing out what was stagnating and in contact with the lead sources.”

Along these lines, the team cautions against drinking hot water.

“You don’t want to use hot water, because the metals can leach more into hot water,” comments McCormick. “We also found staggeringly high levels in water heaters. I personally pulled some of the samples out of the drains of water heaters; the color of the water is just disgusting, and makes me never want to drink the water that comes out of the hot water faucet.”

The team further recommends setting an action level of 5 ppb that will trigger an investigation of lead sources and remediation efforts, until the NSF International 5 ppb leachability standard can be strengthened to reduce lead in new brass fixtures.

“One of the NSF International standards is called NSF ANSI 61, and that’s for new brass fixtures,” explains McCormick. “To comply with that standard, you can’t have more than 0.25 percent lead by weight. However, it can also leach up to five parts per billion on average over about three weeks of use.”

This is linked to the issue of replacing fixtures and being unable to get the lead level low enough.

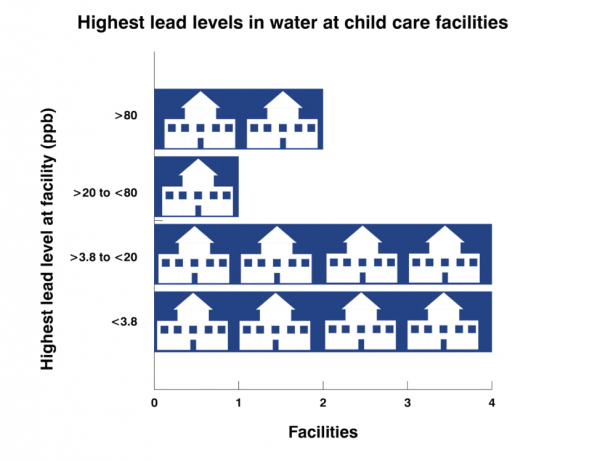

Graphic illustrates the highest lead level detected at each of 11 child care facilities, excluding samples from non-drinking sources such as utility sinks and hose bibs. Our pilot used a health-based action level of 3.8 ppb to trigger remediation. (Credit: EDF, https://www.edf.org/sites/default/files/documents/edf_child_care_report-062518.pdf.)

“We are recommending that NSF International adopt more stringent standards for their new fixtures because if you have new fixtures out on the market that also have lead in them, it’s a little counterintuitive,” details McCormick. “You’re finding lead in the fixture, and then you replace it—and you put new lead in.”

This goes back to the issue of flushing; once fixtures are replaced, it is critical to condition the new fixtures, or flush water through them repeatedly.

“Honestly, after seeing some of the data, I personally would probably filter my water for a few weeks after putting in any new brass fixture,” adds McCormick.

Meanwhile, the team hopes that stakeholders will pay sufficient attention to their findings, and focus on protecting children under the age of six from lead exposure. Although many of their recommendations are relatively easy to implement, they are not necessarily intuitive.

“I know I had never flushed my water heater before,” remarks McCormick. “It’s not something that people think about.”

Top image: Typical fixture and associated plumbing. (Credit: EDF, https://www.edf.org/sites/default/files/documents/edf_child_care_report-062518.pdf.)

Burnice Bauch

May 31, 2023 at 10:39 pm

Removing lead from childcare centers is crucial for protecting the health and safety of young children. This article highlights the importance of identifying and addressing lead contamination in these facilities. Thank you for shedding light on this important issue!