Great White Shark Nursery Location Confirmed

A baby white shark’s (Carcharodon carcharias) migratory patterns in the north Atlantic are tracked using satellite and acoustic technology. (Credit: R. Snow, OCEARCH, http://www.newswise.com/articles/view/697600/?sc=sphr&xy=10020912)

Just when you thought it was safe to read a journal again, a research team from the Harbor Branch Oceanographic Institute at Florida Atlantic University (FAU) has confirmed the presence of a great white shark “nursery” in the North Atlantic Ocean using acoustic and satellite technologies. This marks a notable advancement in human understanding of the needs of this mysterious species at its most vulnerable life stage.

FAU assistant research professor Matt Ajemian provided EM with some insights into the study.

“Nurseries, or areas where young animals spend a significant time growing and hidden from potential predators, are essential to life,” explains Dr. Ajemian. “Little sharks cannot become sharks without this habitat in place, and unfortunately we don’t know where this is for many shark species. While we had an idea where this was for the white shark based on a culmination of anecdotal reports over the years, it was important to confirm this, given that the oceans have changed a bit over recent decades (warming, acidification, etc.).”

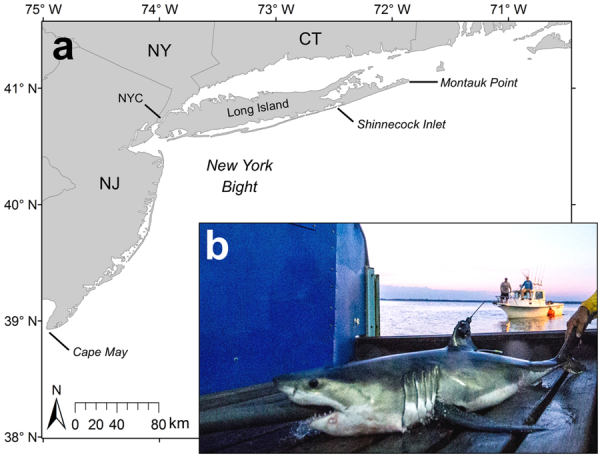

For some species, that means ranges are shifting; for others, ranges are expanding. The New York Bight along the Atlantic coast—which lies between New Jersey’s Cape May Inlet and Long Island, New York’s Montauk Point—has long been a place where scientists have been more likely to spot baby great white sharks. However, to confirm that a location serves as a shark nursery, data must prove three characteristics: more baby sharks than in other places; repeated use over time; and residency by babies in the area for extended periods.

This study confirmed the third point for the New York Bight, and also bolstered our understanding about baby white sharks more generally, providing data on their distribution, habitat-use, and movements.

Tracking baby great whites with tech

The team confirmed the location of the New York Bight shark nursery by deploying acoustic and satellite tags on 10 great white sharks less than 1 year old (“babies”) off the coast of Long Island.

“The acoustic telemetry tag process requires us to attach a chapstick-sized transmitter that emits a unique coded ping with an identification code to the animal, which is detected by acoustic receiver stations that are up and down the east coast of the USA (and beyond),” details Dr. Ajemian. “While this system is great and can pinpoint you to the animal with a few hundred meters, coverage isn’t complete and it requires significant coordination with other groups in order for you to get your data.”

The team also used Smart Position Tags (SPOTs). These tags are attached to the dorsal fin of the animal and have specialized wet-dry sensors. The tag transmits to the Argos satellites circling overhead whenever the sensor is dry—when the dorsal fin breaks the surface of the water. It uses a Doppler-shift algorithm to position the animal based on the behavior or strength of the pings over the satellite pass.

Map of the study site off Long Island, New York in the western North Atlantic (a) and photograph of a satellite tagged YOY white shark (WS2) on the M/V OCEARCH boat lift tagging platform (b). (Credit: Image copyright OCEARCH, from Curtis et al., https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-018-29180-5/figures/1)

“The great thing about SPOT transmissions is that they can be used in near real time, within 30 minutes, to track your animal,” remarks Dr. Ajemian. “OCEARCH has taken advantage of this technology and you can track animals, including the ones tagged in this study, on its great website: http://www.ocearch.org.”

The team then characterized and monitored their habitat use based on bathymetry, distance from shore, and sea surface temperature.

“Using the tracks within the context of geospatial information systems (GIS), we can ‘extract’ data when we overlay our positions onto raster data sets (bathymetry, SST downloaded from satellites),” clarifies Dr. Ajemian. “These data provide us with important information on the habitat of these species such as the depths they’re utilizing so we can identify potential areas where they interact with fisheries. We can use the data from this and SST data to help us model where these sharks are across the entire continental shelf. This is important in delineating the full potential habitat of this species.”

Elusive species demand patience, persistence

Obviously, there are many reasons why it’s very difficult to collect data on sharks in general.

“The electronic tagging approach offered a tremendous amount of data at a somewhat reasonable cost,” Dr. Ajemian states. “The tagging approach certainly beats conducting fishing surveys all over the continental shelf consistently for many months to try and hook up with a baby white. We used prior knowledge of where the sharks should have been, and then got lucky to tag about a dozen individuals and let the tags do the rest of the work.”

Finding the babies to tag demands a very specific skill set—something the researchers recognized from the outset, looking to skilled and experienced fishermen for help.

“Two individuals really made this a reality: Captain Brett McBride of the M/V OCEARCH, who has countless years fishing all over the world for various species, including young white sharks off southern California, and Captain Greg Metzger, a science teacher and avid fishermen who had the local beat. Together, these two individuals were able to collaborate and hone in their methods on catching these baby sharks. This involves everything from finding the correct oceanographic conditions (temperature, currents, etc.) to the presentation of the bait to entice the sharks to bite. In addition, we had some help from commercial fishermen who provided some on-water observations, which are crucial when looking for a relatively rare species!”

Of course, finding the sharks isn’t the final challenge. Tagging them is also an involved process for a skilled team.

“After animals are caught, they are kept in the water and suspended alongside the vessel, facing into the current to ensure fresh oxygenated water flows over the gills,” Dr. Ajemian describes. “Once the animal is safe and secure, we perform our tagging operations like a pit crew. We quickly attach transmitters externally to the animal on non-vascularized areas like the dorsal fin. While this is all happening we are taking measurements of various pieces of the animal, taking small tissue samples for other analyses, and constantly monitoring the health of the animal. It’s like 10 science projects all happening at once!”

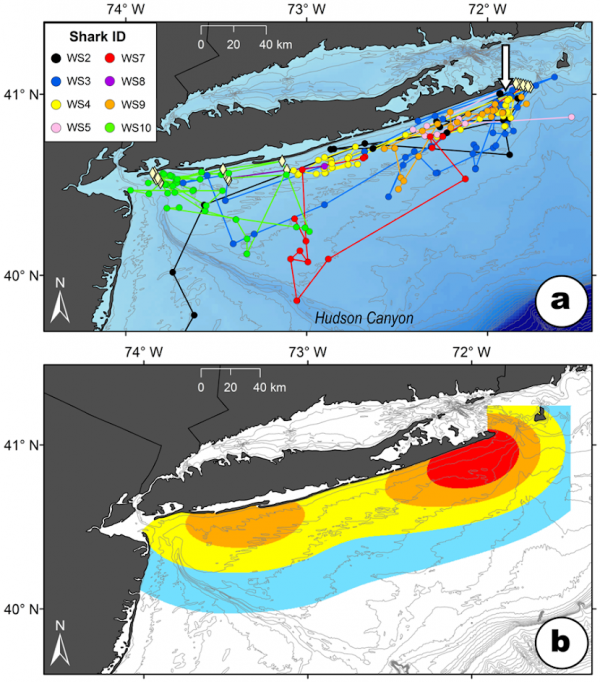

Tracks of eight YOY white sharks (a) and kernel utilization distributions (blue = 95%; yellow = 75%; orange = 50%; red = 25%) of the tagged sharks (b) off Long Island, New York, during August through October, 2016. The arrow indicates the tagging location. Diamond symbols represent locations of acoustic receivers where YOY white sharks were detected. Bathymetric contours (gray lines) are in 10 m increments. (Credit: Curtis et al., https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-018-29180-5/figures/2)

This was the first study to track baby white sharks in this region, likely due to the challenges of funding and conducting shark research in general.

“Sharks are relatively ‘rare’ creatures when you think about their density compared to other organisms of the sea because if there were too many top predators in the sea like sharks, there wouldn’t be enough of a food web to support them,” states Dr. Ajemian. “What that means for us is that they’re ‘few and far between.’ So, we fish hard at a locale, and on a good day we’ll catch a few individuals!”

Funding for shark research is also a challenge; early shark research was supported by the Navy and focused on how to deter sharks and increase the safety of naval personnel at sea.

“Sharks, many of which are exploited for their meat/fins and are thus a commodity, weren’t even managed by the federal government until the early to mid-90s, and we failed to notice their declines from overfishing and other means,” remarks Dr. Ajemian. “Shark ‘conservation’ is still a relatively new idea, but it’s gaining a lot of traction. Support organizations like OCEARCH, who have provided great platforms for scientists to engage in meaningful shark research, have helped bring some of this work to light.”

The data from this study augment other research on great white sharks and reveal a pattern that proves the New York Bight is a primary nursery for great white sharks between August and October. The area offers them a refuge from potential predators, including older sharks; by December, the babies head south, spending winter off the coast of the Carolinas.

“We have regulations in place to ensure adult populations continue to recover, but none of that is truly effective unless we know where the babies are,” remarks Dr. Ajemian. “As for many populations, the real ‘bottleneck’ is at the younger ages, where individuals are generally more susceptible to natural and anthropogenic pressures. The goal for any species is to grow and mature enough to survive, reproduce, and contribute to the population. If we cannot ensure these young sharks have the right habitat to do that—and we weren’t entirely sure where that was until recently—then we cannot assure these little sharks become the big sharks.”

Dr. Ajemian and the team hope that ongoing use of multiple electronic tag technologies and data collection will generate a rich set of long-term data that will allow them and other scientists to more fully characterize the movement patterns of the great white. This, in turn, will assist with practical management efforts.

“This research can be practically applied in several ways, but the main goal is to assist with the management of the white shark in the North Atlantic,” explains Dr. Ajemian. “This is a species that has shown signs of recovery in longline fisheries. However, to ensure white shark populations continue to be sustainable, we need to know where they are at all life stages. Also, there are a lot of energy development activities planned and proposed for the New York-New Jersey area, and we could potentially use these data to inform those groups of how those operations may overlap with and potentially influence such an iconic and ecologically important species such as the white shark.”

Dr. Ajemian adds, “It takes a village! We would not have been successful without the help and support of so many different entities.”

Top image: A baby white shark’s (Carcharodon carcharias) migratory patterns in the north Atlantic are tracked using satellite and acoustic technology. (Credit: R. Snow, OCEARCH, http://www.newswise.com/articles/view/697600/?sc=sphr&xy=10020912)

0 comments