Hawai‘i’s He‘eia NERR Looks to its Ancient Past to Prepare for its Future

Restored wetland at Kāko'o 'Ōiwi in the He'eia wetland, showing the channelized agrosystem (lo'i, or taro farmland), with two Hawaiian stilts (ae'o). (Credit: Shimi Rii)

Just added in 2017, He‘eia National Estuarine Research Reserve (NERR) is the newest NERR in the system, the 29th of 29. It is located in the southern portion of Kāne‘ohe Bay, the largest sheltered body of water in the Hawaiian Island chain, on the eastern shore and the Ko‘olaupoko region of the island of O‘ahu. He‘eia provides a home for several federally endangered species, including: the Hawaiian stilt (ae‘o), Hawaiian moorhen (‘alae ‘ula), Hawaiian coot (‘alae ke‘oke‘o), Hawaiian duck (koloa maoli), the Hawaiian hoary bat (‘ōpe‘ape‘a) and the ‘o‘opu, the Hawaiian freshwater goby.

In addition to its gorgeous vistas, Hawai‘i is also known, from a conservation standpoint, as “The Endangered Species Capital of the World.” It is also the only state in the U.S. whose rare species are guarded by Aunties and Uncles, or the kupuna (elders) of the island.

Hawaiian culture is ancient, and the people in Ko‘olaupoko have not forgotten the ways of the past. “Our kupuna have been fighting against development since the 70s in order to preserve the native Hawaiian culture and landscape,” says Shimi Rii, the new Research Coordinator at He‘eia NERR. “They are our tireless guardians.”

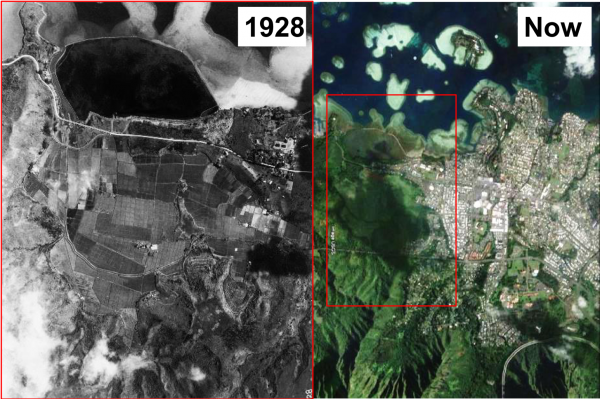

Aerial images of the region in 1928 (Credit: USGS) and now (Credit: NOAA).

In its critical conservation efforts, the newly formed He‘eia NERR has been exploring its past, looking to the ways of the ancient to determine how best to care for the native plants and animals that once dominated the landscape. They want to turn back the clock to a time before the arrival of invasive species.

“We have a conservation vision for He’eia NERR: we want to bring the environment back to the way it was in 1928,” says Rii. “It was a point in history when humans inhabited the area, but invasive species had not yet arrived.” In 1928, ancestral practices were still in place for wildlife and land management, providing optimal sustainability through a natural land division system called the ahupua‘a. Since then, many factors have threatened the natural balance, such as urban development, the arrival of the invasive mangrove and the introduction of invasive California grass.

The effect of the mangroves has been particularly insidious. “The mangroves have changed the sediment composition to silty. This composition, unfortunately, supports non-native species instead of the desirable native species,” says Rii. “We hope to reverse this trend.”

(Left) Invasive overgrown mangroves at the He’eia fishpond (Right) Restoration at Kāko’o ‘Ōiwi – removal of invasive mangroves (Credit: Shimi Rii)

There is a wetland area that the NERR is working to restore, which follows a direct stream from the ancient Hawaiian mountain valleys. “Overgrowth of non-native vegetation is a big negative factor for the health of the wetland,” Rii mentions.

Like other NERRs, He‘eia follows the System Wide Monitoring Program (SWMP). The NERR has instituted a land use restoration gradient, coordinating research in different areas in the reserve. “One of our sites borders an ancient fish pond, which the organization Paepae O He‘eia have been restoring since 2000, well before we were recognized as a NERR,” says Rii. “We’ve already seen improvements in this area. Some of our native birds have started returning, such as the Hawaiian stilt.” There are four SWMP sites, one in the wetland, one in the stream as it enters the fishpond, one bordering the fishpond and Kāne‘ohe Bay, and one in the bay. YSI EXO2 sondes are used at each site to measure properties such as dissolved oxygen, temperature, conductivity, pH and turbidity. Grab samples are taken monthly to analyze nutrients and phytoplankton biomass (using DNA and HPLC analysis) in the water. ISCO equipment is also used for diel monitoring. SET monitoring is done in three control areas and three areas in the wetland with non-native vegetation removed. A weather station is located at Hawai‘i Institute of Marine Biology, with plans for another weather station in the wetland.

(Left) SWMP Technician Dr. Kim Falinski measuring surface elevation in the wetland using RSETs (Credit: Shimi Rii) (Center) SWMP Tech Assistant Gus Robertson getting the YSI EXO-2 ready at one of the SWMP sites (Credit: Fred Reppun) (Right) He’eia NERR RC (Dr. Shimi Rii) distributing feldspar to measure elevation change in the wetland (Credit: Fred Reppun)

The kupuna, Koolaupoko’s Aunties and Uncles, are still hard at work trying to conserve all the habitats. Aunty Rocky Kaluhiwa is one who stands out in particular to the native community. “Her grandfather was the ancient land manager (konohiki) of this place,” Rii explains, “which is incredible for our generation, to have the knowledge (‘ike) of her family guide us in our restoration and land management.”

As far as what drew her to He‘eia NERR, Rii says it was her passion for interdisciplinary science and giving back to the community. “I have always wanted to blend science and culture in a seamless way,” she explains. “So many people want to understand and protect their environment, and the people of Ko‘olaupoko are particularly passionate and proud of restoring their native species and landscape.”

Plans for a citizen or student science group are underway, though there are already many volunteers helping with research and restoration within the He‘eia NERR. Many non-profit organizations have been working to conserve this region for a while, and these partnerships between State, Federal, and NGO’s are what will really get things moving.

“Everyone is really excited about our new NERR,” enthuses Rii. “I am excited to help make a difference.”

Top image: Restored wetland at Kāko’o ‘Ōiwi in the He’eia wetland, showing the channelized agrosystem (lo’i, or taro farmland), with two Hawaiian stilts (ae’o). (Credit: Shimi Rii)

0 comments