Horseshoe Crabs and Red Knots: Delaware NERR Monitoring Offers Glimpse into Coastal Wildlife

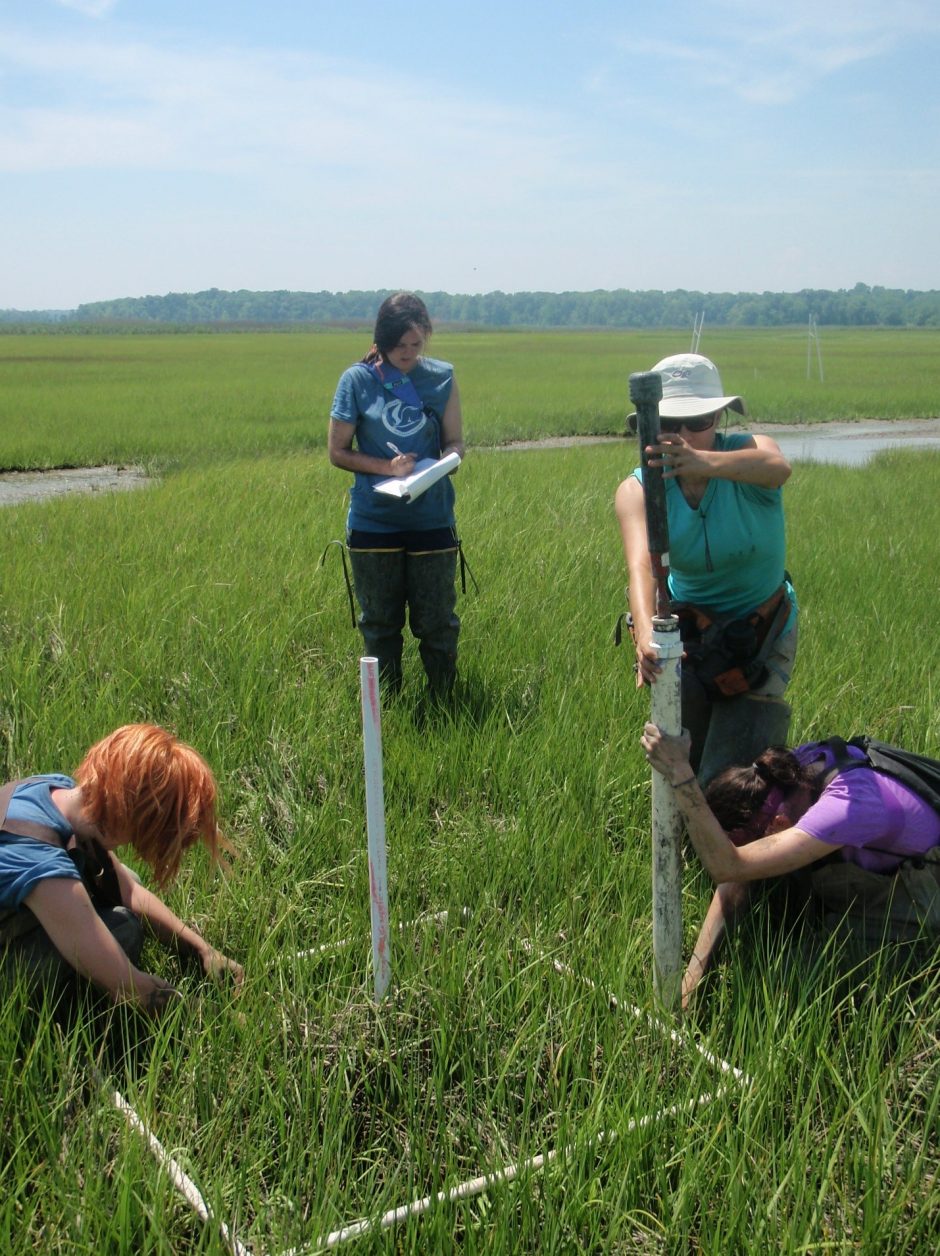

DNERR environmental scientists Christina Whiteman and Dr. Kari St.Laurent measure the soil bearing capacity using a slide hammer, summer intern Molly Williams measures the vegetation stem density, and summer intern Madison Miller records data. (Credit: DNERR)

One of the only 29 National Estuarine Research Reserves (NERR) in the U.S., the Delaware NERR is home to birds, plants and other coastal life that is not commonly seen in much of the U.S. While the Delaware NERR is home for some species, for others it is a must-stop travel destination during their annual migration across the globe.

“Delaware has a wonderful ecosystem with high diversity,” says Kari St.Laurent, research coordinator at Delaware’s Department of Natural Resources and Environmental Control, of which Delaware NERR is a part. “It is a very dynamic area, a place of transition between Northeast and Southwest, where many migratory species can find a high quality, temporary home. It fits what you would think of as a salt marsh to a ‘T.’ It has a high food density and is great for animals who need to refuel on their journeys.”

A suite of environmental monitoring tests are performed to make sure the Delaware estuary system is in good health, so all its visiting creatures will enjoy their stay. YSI EXO2 instruments are typically used to continuously track abiotic water quality information such as: temperature, salinity, conductivity, pH and dissolved oxygen. These data have been taken on Delaware NERR since 1995. In addition, vertical height of water measurements are taken for the estuarine areas, as opposed to water depth. While water depth is expressed in terms of water pressure, vertical height is a measurement relative to 1988 North America Vertical Datum, and can be directly compared. Data are evaluated according to high tide vs. low tide conditions. Real Time Kinematic (RTK) measurements are employed.

Multiple data-gathering sites are used, with sites deliberately chosen that sit on a salinity gradient. There are seven sonde sites on the Delaware Bay, which sits between two rivers, the Blackbird Creek and the St. Jones. The Blackbird Creek is a tidal fresh environment, whereas the St. Jones is more brackish.

Four permanent staff, with support from other staff in the program, overlook the Delaware NERR health, while one to three interns typically help to gather water quality monitoring data in the summer. Most of the interns are undergraduates from all over the country, including Ohio or Delaware universities and major in biology, conservation or restoration science.

“In addition to all the abiotic data we continuously monitor for, we also take monthly nutrient grabs of the estuarine water to check nitrogen and phytoplankton concentrations,” says St.Laurent. “We use an ISCO automated sampler, which takes samples over a tidal cycle, for example from low tide to low tide. It is placed in the coastal waters at the beginning of the cycle of interest and taken out when the cycle is complete.”

While lots of information on the Delaware NERR is taken electronically by sophisticated equipment, lots of information gathering is also done using old school boots-on-the-ground observations by a large number of citizen scientists. “The efforts of the citizen scientists are very important,” says St.Laurent. “They help us count one of our most valuable and unusual species: horseshoe crabs.”

DNREC staff and volunteers count spawning Atlantic horseshoe crabs (Limulus polyphemus) during a high tide full moon on May 25, 2017. (Credit: Drexel Siok)

Numbering anywhere from the tens to hundreds, citizen scientists from all over the country gather in the May to July timeframe every year to count horseshoe crabs. These months are the crabs’ mating season, and it’s the one time of year they come ashore and are easy to count. “They lay hundreds of thousands, or even millions of eggs on shore during mating season,” says St.Laurent. “The citizen scientists record how many crabs they see in a one meter quadrat, over a one kilometer stretch. They also need to record how many males and females they see in each area.”

The male crabs are usually easy to tell from the females, as the females are much larger, and typically there will be several small males on one large female. If the size isn’t a dead giveaway, males also have claws shaped like boxing gloves, which they use to hold on to the female. The females have regular-shaped claws.

While horseshoe crabs are used by humans in various ways, such as when their copper-laden blood is harvested to use to detect bacterial endotoxins in medical settings, or when the crabs are used as fertilizer, the crabs have a very important role for other creatures as well. Many birds eat their eggs as a primary food source during migration. “One of the important species that uses horseshoe crab eggs is the red knot. The red knot is a threatened species, and horseshoe crab eggs are vital for it when it migrates from Argentina through Delaware, going all the way to the Arctic to breed,” says St.Laurent. “The red knot travels more than 9,000 miles, one of the longest bird migrations.”

The horseshoe crabs tend to gather on three of beaches near the Delaware NERR: Kitts Hummock, Bowers Beach and Ted Harvey Beach. From May to July, these are excellent places to see both the crabs and the threatened red knots that feed on their eggs.

At Delaware NERR, not only horseshoe crabs and red knots are counted. Many other birds are too. “We have marsh wrens, sora and clapper rails. Monthly from May to July we do a marsh bird survey. But we don’t do a visual survey for those. We play bird calls, and if the birds are there, we may hear them respond,” says St.Laurent. This data is more qualitative than quantitative, but still gives an idea of whether a population is present or not. The Shannon diversity index can be used with the information gathered as well as algorithms to assess population trends developed by the Saltmarsh Habitat & Avian Research Program.

DNREC environmental scientists Drexel Siok and Christina Whiteman measure tidal marsh surface vertical changes using a surface elevation table. (Credit: DNERR)

Lots of data that has been gathered on the Delaware NERR environment and its creatures have not yet been analyzed.

“We don’t fully understand the impact of Hurricane Matthew in 2016, for example,” says St.Laurent. Understanding the impact of Matthew is complicated by the fact that there was another, smaller storm prior to Matthew which caused flooding and a large salinity dip, even before Matthew arrived. “There’s still a lot of work to be done to understand what has happened to our estuary system, and what could happen in the future,” she says.

About the future of Delaware NERR, St.Laurent is optimistic. “We have a great data collection system, as we use the same system as the other 28 NERR sites, which makes for excellent comparisons of data throughout the whole country. For example, we have been able to clearly see that Delaware and Maryland had unusually large rises in water level compared to the rest of the country. So we know that’s a pressure point for us. Many organizations can’t get the same regional and national perspective we can get because of our unique NERR system.”

Top image: DNERR environmental scientists Christina Whiteman and Dr. Kari St.Laurent measure the soil bearing capacity using a slide hammer, summer intern Molly Williams measures the vegetation stem density, and summer intern Madison Miller records data. (Credit: DNERR)

0 comments