Hotspots and Trends in Water Quality Violations Emerge All Over the United States

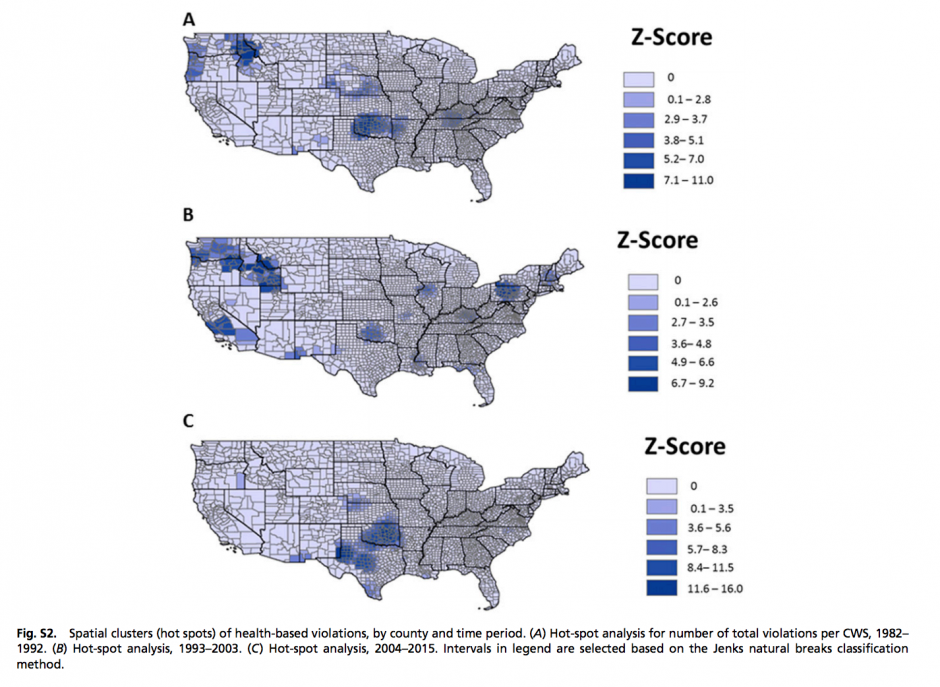

Spatial clusters (hot spots) of health-based violations, by county and time period. (Credit: Allaire et al.)

After the United States—and the world—learned about the water quality crisis in Flint, Michigan, water economist and former Michigan resident Maura Allaire started to wonder just how unique the problem was to Flint. Certainly specific incidents in which a water contaminant crops up somewhere happen in any given year. Just how widespread is the problem?

Allaire researched the issue and found there was no clear answer to that question. Although the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has been collecting data concerning water quality violations all around the nation for more than 30 years, no one had ever undertaken a long-term, national assessment of data trends. Allaire and a research team from the University of California, Irvine began their own assessment to find out what kinds of patterns might emerge.

“The Flint water crisis motivated me to do this research, as a former Michigan resident,” Allaire explains. “While serious violations of drinking water quality standards are rare, ensuring reliable access to safe drinking water poses a challenge for communities across the country. Each year, about 7 to 8 percent of community water systems do not meet health-related standards.”

Hotspots and trends across the nation

The team downloaded data from the EPA and examined how many health-related water quality violations took place across the continental United States in 17,900 community water systems over a 34-year span.

“This is the first national assessment of trends in drinking water quality violations across several decades,” Allaire details. “We conducted a variety of statistical analyses to understand how health-related violations have changed from the 1980s until today and how they vary across regions of the U.S. We evaluated spatial and temporal patterns in health-related violations of the Safe Drinking Water Act. We also identified factors that might increase vulnerability to violations. We assessed how utility size, choice of source water, and community characteristics (income, population density, race) might influence the likelihood of a violation occurring.”

Elevated levels of lead, the problem identified in Flint, were common, but they were not the only problem the team discovered. Violations for arsenic, coliform bacteria, nitrates, and other contaminants were also frequent. The team then drew U.S. census data on average household income and housing density to pair up with water quality violation data to determine “hotspots,” communities which are most vulnerable. Identifying vulnerability factors associated with violations and the hot spots that reveal them indicates which types of communities can benefit the most from assistance with water quality interventions.

The team discovered that almost 21 million Americans—around 6 percent—were drawing their water from systems that violated health standards during the Flint water crisis in 2015. Between 1982 and 2015, the number of violations grew steadily, with spikes at times when new regulations were added. For example, in 1990 a coliform bacteria regulation was enacted, and this caused violations to double within five years, signaling not a sudden drop in water quality, but a new understanding of what should constitute a violation.

“Health-related violations extend well beyond Flint,” asserts Allaire. “During each of the past 34 years, 9 to 45 million people have potentially been affected by health-based violations.”

Causes of hotspots in water quality violations

Idaho, Nebraska, Oklahoma, and Washington, D.C. experienced the most violations. Low-income, rural counties were the most vulnerable areas in the country. The team detected increasing violation hotspots and time trends in Idaho, Oklahoma, and Texas; ongoing, repeated problems highlight the water quality struggles a given community faces and the issues that cause the violations.

Some of these issues include the difficulty small water systems experience in keeping water safe when they can’t afford the best, most recent treatment technology—or in some cases, even a full-time operator. On the other hand, small communities that solve this issue by buying treated water from bigger utilities experienced fewer violations.

Safe Drinking Water Act. (Credit: EPA)

“We find that violation incidence in rural areas is substantially higher than in urbanized areas,” Allaire details. “Rural areas tend to have less capacity to comply with quality regulations and face financial strain due to decline populations and lower incomes. Assistance in achieving consistent compliance and greater oversight may benefit vulnerable water systems.”

Some communities start out with a disadvantage, because their source water is dirty. This is a problem in southern states such as Texas and Oklahoma, which experience high temperatures that nurture bacterial growth. In fact, warm weather can worsen most contamination problems, so prevention is an important strategy. For small communities, purchasing water is sometimes the best alternative.

“Compliance is associated with purchased water source and private ownership,” Allaire explains. Wholesale providers supply this purchased water, applying their superior resources to the problem of meeting federal standards, insulating smaller private utilities from the liability associated with delivering poor quality water.

Public health and policy implications

While not all varieties of water contamination cause public health problems, many, including those examined in this research, do.

“Our study focuses on health-based violations, which include maximum contaminant levels (MCLs), maximum residual disinfectant levels, and treatment techniques,” Allaire describes. “Standards for contaminants that can trigger health-based violations are established by the Environmental Protection Agency and are enforced at the state level. Categories of regulated contaminants include total coliform, nitrate, arsenic, lead, disinfection byproducts, and a variety of other inorganic and organic chemicals.”

The vulnerability factors the findings suggest could indicate the types of systems that might benefit from assistance and targeted public policy.

“Prioritization of technical guidance and financial assistance could benefit underperforming systems,” Allaire explains. “Expansion of training and assistance could address a variety of operational issues, including source water protection and development of procedures for monitoring and maintenance, which are the most common system deficiencies.”

76.9 million people served by community water systems with at least one reported violation of the Safe Drinking Water Act (2015). Populations are shaded at the county level to show the number of residents served by violative community water systems in 2015. (Credit: NRDC)

When possible, communities can band together to better ensure safer water.

“Merging and consolidation of systems, where feasible, could provide a way to achieve economies of scale for adequate treatment technologies,” Allaire details. “Feasibility of consolidation will be influenced by existing infrastructure, distance, and liability concerns.”

Ultimately, clean, safe water is something everyone in every community should advocate for, whether the hotspot is where you live or not. In a nation filled with aging infrastructure, these areas have the potential to become far more common.

“Reducing water quality violations can lead to improved health outcomes and less disparities in water service,” remarks Allaire. “Unfortunately, there are communities in the U.S. that do not have adequate water security. This study informs a more directed approach to increase compliance with drinking water quality regulations.”

0 comments