Monitoring Hurricanes and Predicting Flooding in the Age of Climate Change

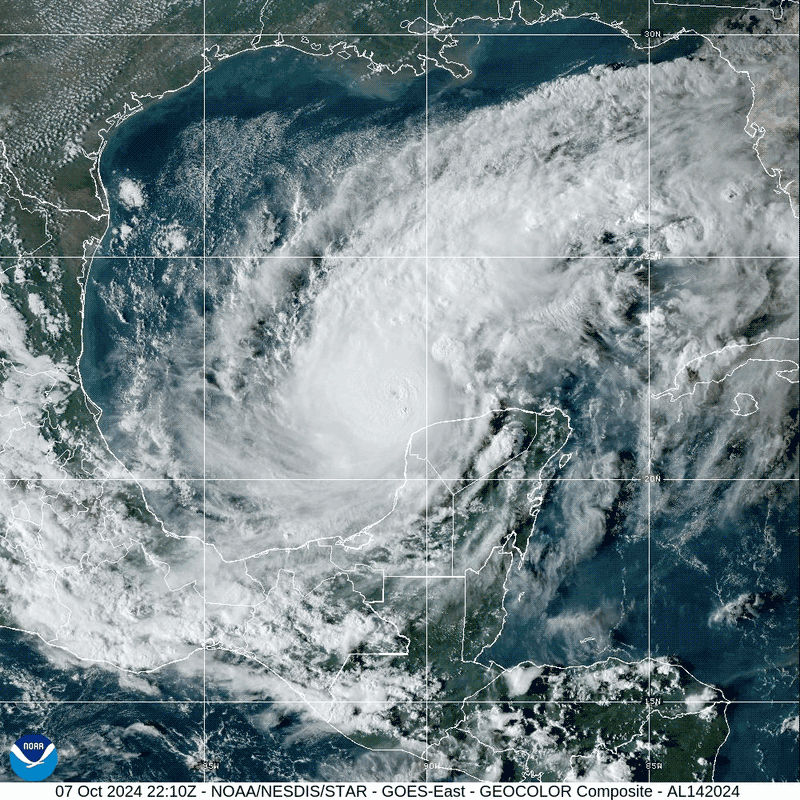

Hurricane Milton rapidly intensifies into a strong Category 5 hurricane in the Gulf of Mexico on October 7, 2024. (Credit: CIRA / NOAA)

Hurricane Milton rapidly intensifies into a strong Category 5 hurricane in the Gulf of Mexico on October 7, 2024. (Credit: CIRA / NOAA)Still recovering from Hurricane Helene, which caused extreme precipitation, flooding, landslides, and other environmental disasters associated with severe weather, the southeastern part of the U.S. is predicted to be hit by another storm, Hurricane Milton.

With Hurricane Helene having made landfall only a little over a week ago on September 27th, many communities are still recovering. ABC reports that over 230 people have been killed as a result of flooding and destruction caused by Helene, with many still missing.

Residents in these heavily impacted states, such as Florida, Georgia, South Carolina, North Carolina, Virginia and Tennessee, are still searching through the rubble of homes, urban centers, and hospitals for loved ones and belongings.

Not even two weeks from Helene’s landfall, Hurricane Milton is projected to hit just south of Florida’s Tampa Bay on the evening of October 9th.

With Hurricane Milton approaching Florida as a category 5 hurricane with 165 mph winds, BBC reports that President Joe Biden has warned Floridians to evacuate as a “matter of life and death.” However, CBS NEWS reports that many in Florida have been unable to evacuate due to traffic, health conditions that limit mobility, financial costs, and other variables that have left some residents in Milton’s pathway.

Two high-impact storms occurring only a matter of days are rare, with Helene wreaking record-breaking devastation and Milton projected to follow suit. Climate change is believed to play a significant role in the frequency and intensity of these storms, creating additional challenges for environmental prediction centers like NOAA’s National Water Center and National Hurricane Center.

Knowing the conditions contributing to the recent surge in storms is only half of the battle for coastal and neighboring states—instead, monitoring changes in storms, hurricane preparedness, early warnings to the public, and enaction of emergency protocols are of greater significance in the moments leading up to the hurricane as well as keeping residents informed during the storm.

U.S. Airmen assigned to the 202nd Rapid Engineer Deployable Heavy Operational Repair Squadron Engineers (RED HORSE) Squadron, Florida Air National Guard, clear roads in Keaton Beach, Florida, after the landfall of Hurricane Helene, Sept. 27, 2024. (Credit: The National Guard via Flickr CC BY 2.0)

How are Hurricanes Monitored?

Hurricane monitoring generally starts at sea, with the National Hurricane Center (NHC) utilizing available data collected by satellites, aircrafts, ships, buoys, radar, and other observations.

Important parameters such as precipitation and wind speed contribute to critical data used in flood prediction and to inform relief agencies and officials how severe the storm will be. Satellite imaging allows the NHC to see the size, movement, eye, and other characteristics of the storm.

The NHC analyzes the data, which is then entered into hurricane forecast models and creates various predictions for the hurricane (rainfall, path, duration, etc.) using existing real-time data. Based on the sustained windspeed of the hurricane, the storm is classified on the Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Wind Scale—with a category of 1, 2, 3, 4, or 5.

How are the Impacts of Hurricanes Predicted?

Most hurricane impacts occur based on wind speed and flooding, both storm surge and inland flooding. While wind speeds can be threatening and lead to property damage, flooding is typically more dangerous as it can result in the destruction of infrastructure, homes, and businesses, as well as possibly trapping people in their homes or cars where they may drown or become stranded.

Flood prediction modeling relies on data from the National Weather Service (NWS), the USGS stream gauge network, and various soil monitoring sites to calculate the severity of flooding and how these events will impact residential, commercial, and ecological areas. The foundational modeling system is the National Water Model, which blends meteorological and hydrological data to predict flood extent and severity.

A Flood Inundation Map (FIM) is a real-time, detailed, actionable, street-level map that depicts the areal extent, depth, and infrastructure impacted by flood waters, explains Ed Clark, director of the NOAA National Water Center. These maps can be monitored continuously and will update as input data changes.

Ed Clark explains, “These models are continuous. Which means that the model has a knowledge of what happened in the past—and they really go back months—because each time we cycle the model, not only do we look at what the future conditions will be from the numerical weather prediction, but also the past.”

Photo of damaged furniture piled on the side of the road on Anna Maria Island following Hurricane Helene. (Credit: Teddy Grigsby)

The prediction can then be distributed to partners and collaborators, including disaster relief organizations, local agencies, state governments, and other key players in disaster response. In the case of Helene, the NWC actively monitored flood potential to critical infrastructure using the Flood Inundation Maps.

“The NWC actively monitored the flood potential to critical infrastructure using Flood Inundation Maps and shared areas of concern in collaboration with National Weather Service (NWS) field offices and partners, including the American Red Cross who was concerned about the safety of their shelters and access to those shelters,” states Clark.

He continues, “For the first time ever, the NWC posted forecast FIMs on social media to alert the communities of Asheville and Bakersville. The NWC shared forecast FIM with NWS field offices who relayed it to their partners. One example here was Unicoi County Hospital in Erwin, TN.”

How Hurricane Helene Will Influence Impacts of Hurricane Milton

While some of the regions hit particularly hard by Helene, like North Carolina, are not currently in Milton’s path, Florida will likely suffer greater impacts from the flooding due to debris still remaining after Helene.

Many natural storm impediments and diversions like rivers, streams, lakes, flood plains, runoff basins, and ponds have already been inundated with water from Helene, leaving Milton’s rainfall to overflow into residential areas.

High flow rates and water levels recorded by the USGS stream gauge network following Hurricane Helene indicate that rivers are at capacity, influencing flood projections for Milton over portions of Florida.

Saturated soil conditions increase flood potential as less water can be soaked up by the earth. In the case of Hurricane Milton, the proximity to Helene means that the Tampa Bay area will see more flooding than if the state had experienced normal rainfall for this time of year or was emerging from a dry spell.

Because there is still debris scattered throughout impacted areas, flood waters and high winds could carry dangerous objects through the air or water, though the state and federal government have mobilized cleanup efforts to remove as much debris as possible before Wednesday night, according to the New York Times.

0 comments