Lake Erie HAB Monitoring Network Matures to Protect Drinking Water

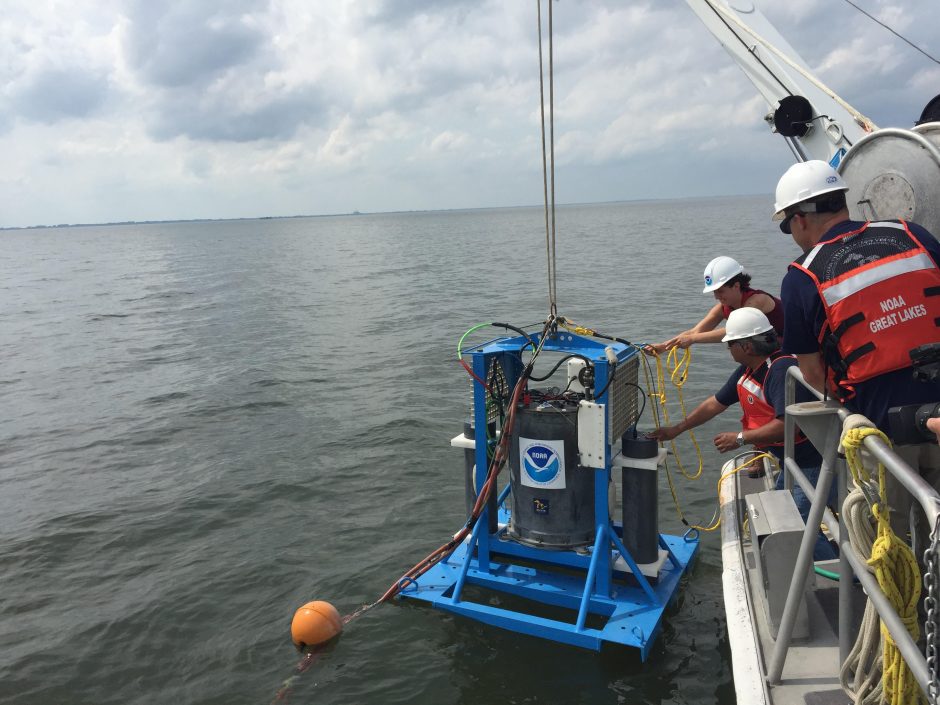

The Environmental Sample Processor will deliver real-time offshore toxin concentrations. (Credit: NOAA/GLERL)

When toxic algae in western Lake Erie cut off 500,000 Toledo residents from their tap water in 2014, an effort to cobble together an algae-monitoring sensor network sprang up in the bloom’s slimy green wake.

This September, as another bloom spread across the western basin, the coalition of water quality interests behind the project secured more than $2 million in backing to bolster it with the best available toxin-monitoring technology, refine the way it distributes data to the people who need it, and ensure it stays funded well into the future.

“We’re really building a sustainable funding model, unifying the network and solidifying it as a permanent observatory,” said Ed Verhamme, engineer with LimnoTech, one of the partners on the project.

The network grew from a plan to install sondes measuring algae pigments and other dimensions of water quality near the intake pipes of drinking water treatment plants along the lake’s southwestern and central shore. What started as a goal of getting seven plants on board the first year has grown to 12 plants sharing real-time sensor data today.

“It helps them know the treatment that they are using is effective,” Verhamme said.“And if it’s effective today and the data shows the bloom is going down, they know it will be effective tomorrow.”

Since the Toledo crisis, several universities and the NOAA Great Lakes Environmental Research Laboratory have launched buoys with similar capabilities across the basin to track conditions offshore. The Great Lakes Observing System, which won the new funding from a grant from its parent organization, made real-time data from most of those sensors publically available in a centralized online data portal.

A growing library of real-time data and other resources are available on the GLOS HAB portal.(Credit: Great Lakes Observing System)

“Between buoys and sondes, it’s around five and a half million data points that are being generated per year,” Verhamme said.

The improved network will provide water treatment plants early warnings for an algae problem that, despite national attention, isn’t getting any better. Though Ohio drinking water hasn’t been compromised since 2014, some residents are still skeptical of what’s coming out of their taps. The 2017 bloom was among the most severe since 2000 in terms of the sheer amount of blue-green algae growing in Lake Erie, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. The 2015 bloom was the most severe since 2000 by the same metric.

But this year’s bloom was less toxic. The disparity between algae biomass and toxin concentrations has posed a challenge for remote, sensor-based measurements of the blooms, according to Timothy Davis, associate professor of biological sciences at Bowling Green University. To help fill that gap, the NOAA Great Lakes lab brought in an Environmental Sample Processor, a cutting-edge moored instrument capable of remotely measuring algae toxin concentrations in the lake.

Treatment plants routinely test for toxins in their labs, but they’re testing water that has already arrived at the plant. That could put them a step behind when it comes to adjusting treatment to remove the toxins. Offshore toxin measurements have previously depended on sampling cruises that rarely happen more than once a week. Pigment sensors are a good indicator of algae’s presence, but not necessarily toxicity.

“You can have pigment concentrations shift over the course of the bloom and yet your toxin concentrations will not,” Davis said. “Instead of proxies, which can underestimate or overestimate risk, we’re measuring concentrations of the toxin itself, which is always ideal.”

Davis was part of the team that brought the instrument to Lake Erie in 2015, making it the first ESP to operate in freshwater. He and colleagues at GLERL have spent the past two bloom seasons testing the instrument in the lake, fine-tuning the automated processes that extract and measure the toxins.

Sonde measurements of phycocyanin have tracked well with microcystin concentrations at the Toledo water intake. (Credit: Ed Verhamme/LimnoTech)

The new grant will bring an additional ESP to the lake, with more funding from the federal Great Lakes Restoration Initiative covering a third. The ESP can’t house enough raw materials to perform daily toxin tests for the entire bloom season, so three instruments will cover two locations in bloom-prone Maumee Bay while one undergoes maintenance and a restock.

The ESPs will be moored where they can intercept toxin-laden water moving toward major intakes. Paired with all the other water quality data being collected around the lake, treatment plant operators and water quality researchers will have an unprecedented characterization of the lake’s bloom ecology and dynamics.

“We can utilize all that data, put it together, and get fine-scale resolution on toxin concentrations, pigment concentrations and dissolved oxygen, which is something we’ve never been able to do before,” Davis said.

Much of that data will likely be available on the HABs Data Portal operated by the Great Lakes Observing System. GLOS built the tool to meet the immediate need borne from the Toledo crisis to host all of the new monitoring data in an easily accessible, central location. They were committed to updating and maintaining the portal, but the circumstances weren’t ideal.

“The HABs portal we developed at GLOS was not necessarily something that we planned to do or that we had a budget dedicated for,” said GLOS Executive Director Kelli Paige. “We were working off the side of our desk a bit and trying to be responsive.”

But the new grant will help GLOS run and improve the portal for the three-year funding period. It also supports work with the Cleveland Water Alliance to engage financial stakeholders to develop a long-term funding model, Paige said. They’ll also be reaching out to users like plant operators to make sure they’re getting the data they need delivered in a way that works for them.

There are also plans to expand the portal beyond the data coming in from the growing number of sensors in Lake Erie. That could include, for example, the biweekly NOAA HAB Bulletin that describes bloom conditions and forecasts how it might change based on modeled water currents and other factors. There are plenty more projects related to algae blooms and Lake Erie water quality, and more researchers are coming to GLOS to look into how all the data products out there can be collated with contextual data in an updated interface of the HABs portal, Paige said.

“It’s validating to see that everyone is naturally coming together around this idea that we should be making the data available — that is a paradigm shift; that it should be somewhere convenient where everyone can find it; and that GLOS is the place for that.”

Pingback: Lake Erie HAB Monitoring Network Matures to Protect Drinking Water - Lake Scientist