Lake Michigan Yellow Perch Bounce Back After Commercial Ban

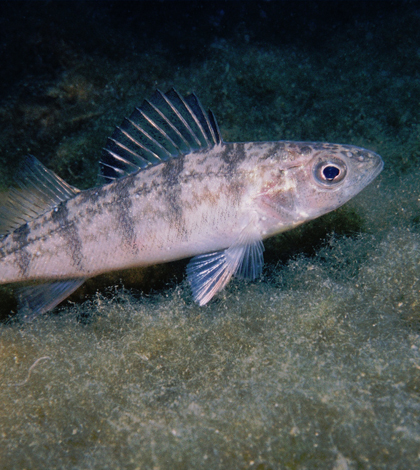

Juvenile yellow perch. (Credit: Roger Tabor / U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service)

For decades, commercial fishing for yellow perch was allowed in southern Lake Michigan. This persisted until 1996 when it was outlawed, giving perch stocks there some time to recover.

Scientists had for some time assumed that this fishing ban would not affect the reproduction cycles of the perch quickly and that they were going to need a long time to revert back to the cycles they relied on before commercial fishing ever started. But new research led by scientists at Purdue University finds that maturation schedules of yellow perch in southern Lake Michigan are much more resilient than had been previously thought possible.

In a span of only a few decades, researchers say, Lake Michigan yellow perch have switched from spawning earlier and at a smaller size back to reproducing later and at larger sizes. Full results of the investigation, which relied on reams of data from departments of natural resources from many states and Ball State University, have been published in the journal Evolutionary Applications.

The data analyzed came from as early as 1970, meaning that the fish represented in these datasets were born as early as during the 1960s. That starting point also means that the study covered both periods, when commercial fishing was allowed and when it was banned. Lake Michigan was not the only lake from which data came. Others include Lakes Erie and Huron, but it is Lake Michigan whose perch yielded the most surprising finds.

Much of the work centers on the idea that humans have up-ended the typical structures of how fish survive. Normally, for most any type of animal, the bigger and stronger are more likely to survive in the wild than those that are smaller and weaker.

“Under natural conditions, smaller fish are more likely to starve or be eaten, but fishing has switched around the mortality selection so that larger fishes are now more likely to die,” said Tomas Hook, associate professor of forestry and natural resources at Purdue and associate director of the Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant. “In gill nets, smaller fish can swim through large mesh. In recreational fishing, you can only keep fish over a certain size.”

And so, with those sort of dynamics in mind, he and others worked with the study’s lead author, Zachary Feiner, a doctoral student at Purdue, to show how this sort of “size-selective fishing” can affect the maturation schedules of five populations of Great Lakes yellow perch.

Hook says that there has long been speculation that size-selective fishing can have adaptive effects on certain traits, but it’s difficult to differentiate adaptive versus plastic responses in a natural population. So when researchers suspected that fish might be maturing faster as a result of size-selective fishing, they had to show it using statistical models that accounted for environmental and ecological effects on growth and mortality.

Lake Michigan sand dune. (Credit: Public Domain)

“They show there have been these drops in maturation schedules, that they’re reproducing at smaller sizes at a given age,” said Hook. “We looked at populations of yellow perch where there was intensive, size-selective harvesting through commercial fishing. However, in Lake Michigan after they closed the commercial fishery, the maturation schedules rapidly recovered (over a period of decades).”

Hook says researchers have previously used simulation models to gauge how maturation schedules might change when fishing is ceased. Most such previous analyses suggest that recovery would take a very long time.

“If you just stop fishing, you wouldn’t expect maturation schedules to recover so quickly, because intensive fishing can remove genetic variation,” said Hook. “What we actually found for Lake Michigan yellow perch after size-selective commercial fishing ceased was that their maturation schedules went back up.”

The rapid recovery of this stock’s maturation schedules may be related to certain attributes. Hook says perch generally have a short generation time compared to many other harvested fishes. In addition, this area of the lake was likely infiltrated by other strains of yellow perch that might have helped stocks there recover more quickly.

“Yellow perch in Green Bay are genetically distinct, but their larvae may drift down, as well as those from yellow perch in smaller systems connected to Lake Michigan, like Muskegon Lake, Milwaukee Harbor and Kalamazoo Lake,” said Hook. “It’s possible that those perch introduced new genetic material and sped up recovery of maturation schedules.”

The results of the work are illuminating for a lot of reasons. And Hook says he and others aren’t sure if the perch are now maturing and spawning at appropriate sizes and ages, but simply that they’re spawning later and at larger sizes after commercial fishing has ceased.

“This study demonstrates how fishing can influence maturation schedules. However, it should be noted that this rapid recovery is not the norm,” said Hook. “So, I don’t think this study should be used as ammunition to allow for over-exploitation (of fish stocks). We don’t think most stocks will behave this way. There’s something particular in Lake Michigan’s yellow perch that allowed for their recovery of maturation schedules.”

Top image: Juvenile yellow perch. (Credit: Roger Tabor / U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service)

0 comments