A manta ray highway: Studying a poorly understood fish in Palmyra Atoll

A gliding manta ray (Credit: Gareth Williams)

The manta ray glides through the water with a grace matched by few other fish. For centuries, these mysterious creatures have drawn the attention of humans, provoking a range of responses from fear to awe to intrigue. Hunted into modern times for food, leather and purported medicinal properties, the manta wasn’t protected as a vulnerable species until 2011.

In spite of its relative popularity, the manta ray remains an enigma in many ways. That’s why Douglas McCauley, assistant professor at the University of California, Santa Barbara, led a study in one of the few places where this endangered species still gathers in large numbers: Palmyra Atoll.

“We were really shocked to find how little scientists know about such a popular, such a conspicuous and elegant animal,” McCauley said. “I’m trying to understand how the loss of large animals influences the function of the rest of these ecosystems.”

Briefly occupied as a U.S. naval base in World War II, Palmyra now houses a small, temporary complement of rotating scientists employed by the U.S. government, The Nature Conservancy and the Palmyra Atoll Research Consortium. The atoll features a large reef, 50 partially connected islets and two shallow lagoons.

“Isolation has afforded de facto protection for the reefs there,” McCauley said. “It’s been kind of doing its own thing in the middle of the Pacific.”

But mantas aren’t there for the getaway. The lagoons at Palmyra and other atolls provide a perfect spot for mantas to munch on zooplankton floating in the warm, shallow water.

A Palmyra Atoll islet from the shallow, warm waters that surround it (Credit: William Anderegg)

McCauley and his colleagues employed several techniques to study the elusive manta rays, from high-tech to admittedly outdated. But McCauley sought a comprehensive understanding of the fish, and one method in isolation wasn’t going to cut it.

The first part of the study took advantage of the atoll’s geography to observe mantas where they gather on their way into the lagoon.

“The main passageway into Palmyra lagoon is a single channel,” McCauley said. “It’s sort of like a manta highway…as they come from the great blue yonder, the pelagic ecosystem. Often we’d see trains of mantas, nose-to-tail, passing in and out of the field of view of this passageway.”

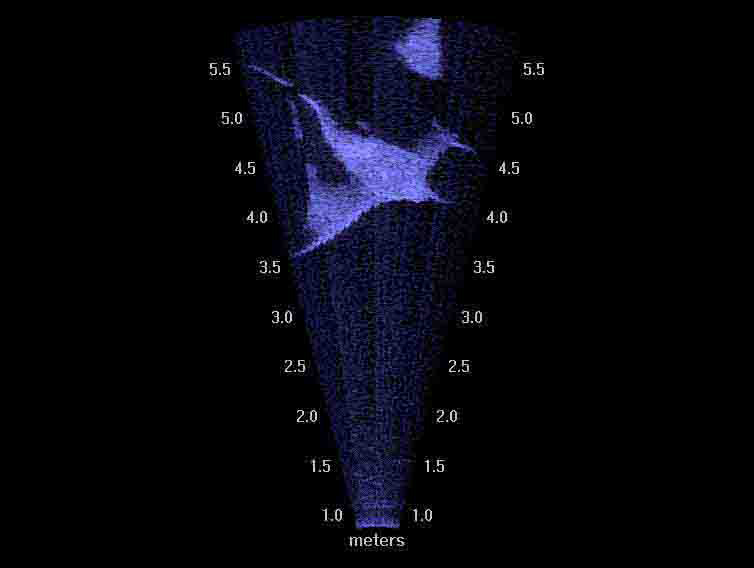

A shot of a manta ray from the sonar camera (Credit: Douglas McCauley)

Using a Sound Metrics DIDSON 300m sonar camera, the researchers set up a “sound gate” across three-quarters of the channel. Anything passing in front of the instrument over the next month — whether manta, turtle, shark or swimmer — was caught in near-video clarity. With no power on that end of the atoll, the researchers used a Navy piling from World War II as a base for a makeshift power station.

To get a better sense of the mantas’ movements, the researchers used a method that McCauley called “a step back in technological time.” They affixed acoustic pingers onto some rays, then, with only their eyes and a hydrophone to guide them, followed the tagged creatures for hours in a boat while GPS units recorded their movements. Though the technique afforded an intimate glimpse into the mantas’ lives, it was far from easy.

“It requires being with the fish at all times, which is a mind-numbingly wonderful experience,” McCauley said. “As is the case with a lot of highly mobile marine animals, they’re there with you in one moment and off in the blue in the next.”

Stanford student Paul DeSalles following rays (Credit: Douglas McCauley)

Researchers took 6-hour shifts tracking the mantas around the clock. Sometimes, McCauley said, this meant weathering squalls through the night, taking shelter beneath a tarp or lifejackets for warmth.

In the end, the researchers discovered manta behavior that could lead to improved conservation efforts. While the manta’s propensity for long-distance travel is known, the researchers found that the creatures return to their favorite spots — specifically lagoons — time and time again.

“If you can actually figure out where the favorite spots are for an animal…then we stand a much better chance of being able to protect them,” McCauley said.

Image: A gliding manta ray (Credit: Gareth Williams)

0 comments