Maui Scientists Offer Water Quality Testing in Wake of Wildfires

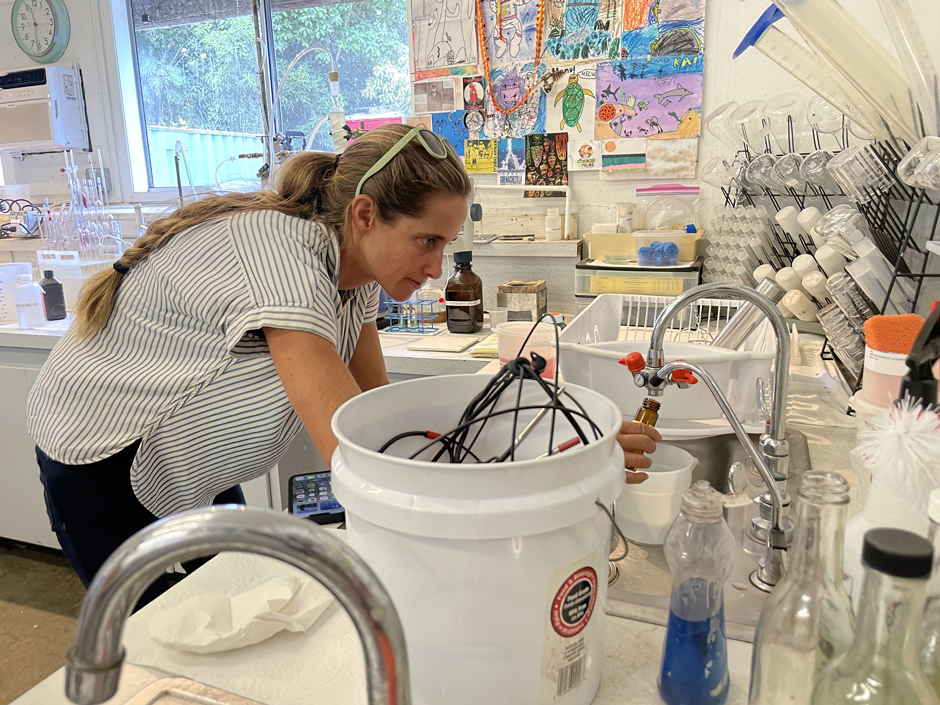

The work of University of Hawai’i employees helps inform regulatory decisions from state health and water agencies about the safety of residential drinking water. (Credit: Chris Shuler)

The work of University of Hawai’i employees helps inform regulatory decisions from state health and water agencies about the safety of residential drinking water. (Credit: Chris Shuler)On August 8th, 2023, news broke of wildfires ravaging the island of Maui, Hawai’i. In the following days, news of four separate fires broke. Wildfires raged in the historic Lahaina village on the western side of Maui to those that burned in the mountainous region in the center of the island.

After weeks of battling and finally containing the fires, the residents of Maui were faced with the arduous task of rebuilding their communities. One priority was ensuring that people impacted by the fires had access to safe drinking water, as the blazes had damaged pipes carrying water to residential and urban areas. Many of these underground water carriers are plastic, and the heat from the fires melted pipes, potentially introducing harmful gasses and volatile organic compounds (VOCs) into drinking water systems.

Community Outreach by the University of Hawai’i

In the wake of the devastation to communities in Maui, state and local governments rushed to set up plans to ensure the continued safety of those living in affected areas. However, official outreach was limited with the scramble to devise a response.

“There’s no playbook, and so the Department of Water Supply, which is just a water utility responsible for delivering clean water, was the one trying to figure out what their response to this unprecedented disaster was going to be,” says Chris Shuler, a hydrologist at the University of Hawai’i (UHM) Water Resources Research Center (WRCC) who is based out of Maui. “They didn’t really have the time for public outreach. So we tried to step in and help fill that role.”

Shuler and his colleagues at UHM set up a hub online to serve as a base point for residents concerned about the safety of their drinking water. Though not associated with the Department of Water Supply (DWS) or Hawai’i Department of Health (DOH), the hub acts as a place to provide information and answer questions from impacted communities.

Moreover, residents can use the website to request water quality sampling tests on their property, which will be carried out by community members hired by UHM.

“We actually go to their houses […] We hired three employees who are community members themselves and live in or very near the burned areas,” Shuler says. “They are taking water samples as a kind of part-time employment and their contribution to the project and their contribution to their neighborhoods.”

Water samples taken from residences on Maui were sent to a University of Hawai’i lab on the Island of O’ahu, where university employees analyzed the results. (Credit: Chris Shuler)

Using gas chromatography-mass spectrometers (GCMS), scientists at UHM are able to detect and quantify the level of VOCs in water samples. Samples are sent to a lab at UHM on the island of O’ahu, where results are then emailed to homeowners and posted online for community members to see VOC levels around the island.

These samples are not meant to show whether water is safe to drink but are rather used as non-regulatory screening looking for contaminants. According to the WRCC, “[The results] will produce research quality, screening-level data that can be used by homeowners, DOH, and DWS to target regulatory level testing and produce data that can expand our understanding of our water quality at a community level.”

Between letting residents know what’s in their drinking water to providing baseline data to DOH and DWS, Shuler has no doubts about the importance of his and the WRCC’s work.

“What we’re doing is really an outreach and informational service,” Shuler says. “We’re not determining the safety of people’s water because we’re not a regulatory agency […] But what we’re doing is, you know, it’s to provide information and outreach for people who are interested.”

The WRCC modeled its community outreach in Maui after their response to the Red Hill water contamination incident on the island of O’ahu in late 2021, where petroleum from a fuel storage facility began leaking into the island’s aquifer.

Shuler explains that UHM employees on O’ahu set up a similar response to the one currently happening on Maui, where they responded to residents who were concerned about the safety of their water, with tests still being done two years after the incident.

“Our hope is to be able to do this, to be funded to do this, until the need for it and the demand for it is no longer there,” Shuler says.

Samples are labeled and kept track of, as the results are uploaded to a community hub online for Maui residents to use. (Credit: Chris Shuler)

Response from residents of Maui

With all of the strategic and regulatory support coming from state and government agencies in response to the wildfires, Shuler sees that the communities of Maui appreciate his and his colleagues’ work on the ground in impacted communities.

“The fact that we’re able to take the time to go door-to-door and to actually be in neighborhoods talking to people and directly connecting with people one-on-one allows us to really connect with folks and build trust,” Shuler says. “[We want to get] the best available, scientifically rigorous, educated information that we can provide them.”

The outreach and education from the WRCC are not just for local residents but are also being used to inform the world of what is truly happening in Maui. Shuler has conducted interviews with TV stations, local newspapers, and international publications to spread the word on how the communities of Maui are responding to the devastation they have faced.

Footage of the wildfires destroying ecosystems and buildings was shared across the internet, but the struggles of residents to return to safe daily lives and the help provided by other community members are often unseen. During the months of work to rebuild communities damaged by the fires, Shuler has observed and appreciated the response from those who live on Maui and beyond.

“This water testing thing was really just, you know, our way of standing up to help when it was needed. We happen to be water scientists, so that’s what made sense for us to do,” Shuler says. “That was a way that we could contribute, and I feel like everybody across the whole island kind of felt a responsibility to help however they could.”

The people of Hawai’i deeply value their land, water, and history. Yet, in the wake of this catastrophe, a combination of scientific research and testing, dedicated citizens, and a sense of community came together to push past adversity. Safe drinking water is essential to humanity, and it was partly through the work of water scientists at UHM that the communities of Maui can start the long process of feeling better about the water they rely on.

Lori Arakawa

April 20, 2024 at 2:33 pm

How do we contact you to request to test our water?

Samantha Baxter

April 23, 2024 at 2:19 pm

Hi Lori,

You can fill out the request form here (https://forms.gle/msGPwz1QJN1o83Bh9. If you’d prefer to go through the hub mentioned in the article (https://www.wrrc.hawaii.edu/maui-post-fire-community-water-info-hub/), you can find the link and a QR Code about a quarter of the way down the page.