NOAA deploys both static and dynamic audio recorders in search for North Atlantic Right Whales

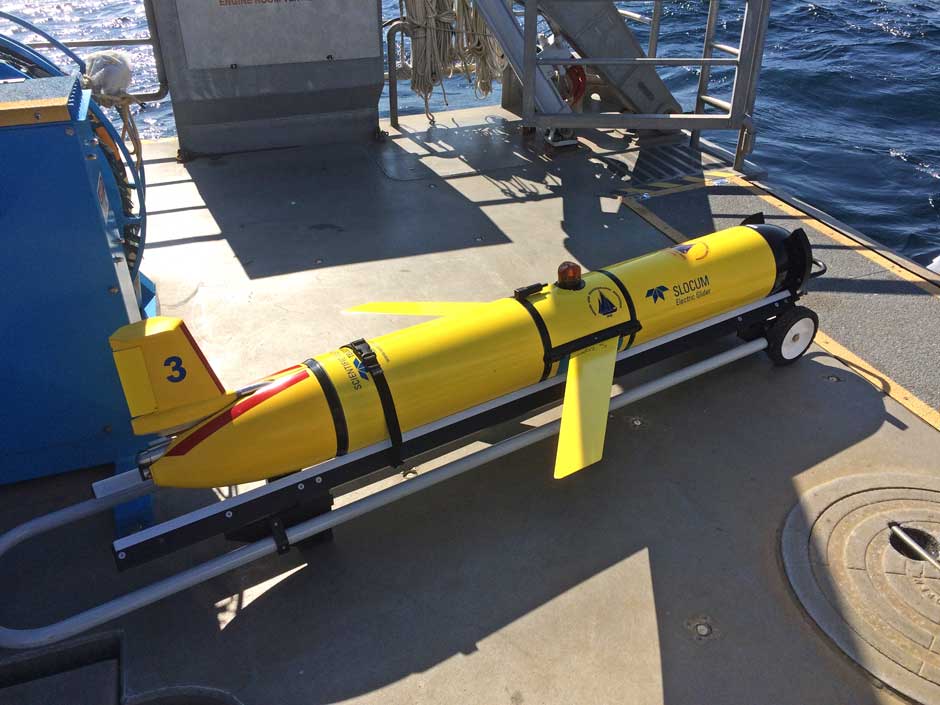

A Slocum glider that navigates on a fixed path along the coastline of the Atlantic Ocean, where it listens for calls from several species of whales. As it picks up frequencies from whales, it will wirelessly transmit that data to servers on land for researchers to look over and analyze. (Photo credit: Mark Baumgartner, WHOI)

A Slocum glider that navigates on a fixed path along the coastline of the Atlantic Ocean, where it listens for calls from several species of whales. As it picks up frequencies from whales, it will wirelessly transmit that data to servers on land for researchers to look over and analyze. (Photo credit: Mark Baumgartner, WHOI)Ever heard of an “up-call?”

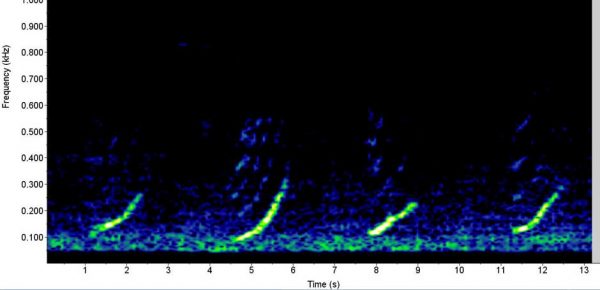

If you’re one of the researchers at the Northeast Fisheries Science Center, it’s likely you have. Considered the primary vocalization of North Atlantic right whales, experts characterize the low-sounding thud as a short whoop. The call’s frequency rises from around 100 Hz to 300 Hz over approximately two seconds, taking on the audio similarity of a drum pad vibrating after being struck. Scientists consider right whale’s “up-call” to be a detection or “contact” call.

Or, in human speak, “Hey, are you there?”

This, among the several other vocalizations made by the mammal, represents the latest category of data that scientists in the Passive Acoustic Research Group are honing in on to better understand the elusive species.

“This project stems from an understanding that we need to know more (about right whales),” said Genevieve Davis, a senior acoustician at the Northeast Fisheries Science Center. “Right now, there’s less than, or just around 400 individuals. It’s hard to say what their role in the ecosystem is at this point because there’s just so few of them, but like all large whales, they play an important role in nutrient cycling.”

Once numbering in the thousands, recording a North Atlantic right whale can be tricky. On top of their endangered status, the species doesn’t vocalize its presence much to begin with. This is why researchers like Davis are deploying a two-pronged approach to tracking the whales: a static archival-acoustic recorder and an autonomous real-time reporting glider.

Together, the acoustics-capturing agents are helping researchers comprehend the soundscape around the Gulf of Maine. The hope is experts will better understand the migratory patterns of right whales, which have been shifting over the last few years.

“With acoustics, we’re able to get animals that are underwater that are vocalizing and we’re able to get them at times where we can’t go out and look for them,” Davis said. “They’re a good complement to the visual surveys.”

While both the fixed audio recorders and the underwater gliders both collect sound, they’re used in very different ways.

Anchored off the coast of Maine, eight fixed-acoustic recorders will collect sound while placed at the bottom of the seafloor. Teams at the Northeast Fisheries Science Center have used recorders called SoundTraps – which measure about the size of one’s forearm and are lighter and easier to deploy than previous models, like Marine Autonomous Recording Unit (MARU).

A SoundTrap acoustic monitoring tool used by the Northeast Fisheries Science Center. As opposed to the dynamic gliders that move up and down the water column, the center’s SoundTrap tools are fixed recorders placed in eight locations off the coast of Maine. (Photo credit: Genevieve Davis)

For about three months at a time, the recorders will record all sounds within its range. Once that time is up, scientists navigate out to the device, download the data that’s been recorded, change the batteries and redeploy the device. This cycle will be repeated four times throughout the year.

At the same time, Slocum gliders navigate coordinated grids off the same coast, collecting similar frequencies as they travel through the water column. Except, every hour or two, it’ll transmit any data that’s been collected back to land, where researchers can dissect the audio.

At their desks, researchers like Davis will review the recordings on spectrograms and try to identify which ones match that of right whales. It could be the up call that’s most common; the male breeding call referred to as a gunshot or a scream call produced by the focal female.

“They (right whale calls) are relatively unique, but humpback whales are our main culprit of the mockingbird,” Davis said. “They’ll produce really complex songs with very patterned notes that change every year and between seasons. Often, like this year, a humpback whale song includes a note that sounds exactly like a right whale’s up call.”

Of the four whales that analysts watch out for, humpback whales are some of the noisiest. Sei and Fin whale calls also make appearances on the acoustician’s spectrograms. To help narrow down some of the potential audio that could be recorded by the gliders and fixed-hydrophones, scientists can specify frequencies of interest. For right whales, a range between 100 and 300 Hz is targeted.

Computer programs developed by Mark Baumgartner at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) further narrow down recordings by identifying specific call types. From there, it’s up to the trained ear of audio analysts to decipher through the interference.

Even if that interference – the sounds of other mammals in the area – aren’t relevant to current research, it’s proven to be valuable for other projects. Those audio files are collected and stored for later use, so if scientists want to go back and assess the presence of other whales in the area, the option is available.

Records of every possible right whale detection eventually find their way to WHOI’s website, which keeps track of each call, the time it came through, and the location of where it was recorded.

An image from a spectrogram showing four successive “up calls” from North Atlantic Right Whales, one of the mammal’s primary vocalizations it uses as a contact call when it’s looking for other right whales. (Photo credit: Genevieve Davis)

It’s here that the public can track the presence of the species and its migratory patterns. While the whale species’ locations are closely tracked these days, that wasn’t the case a couple of decades ago. The species was decimated by commercialized whaling in the last century and their numbers haven’t recovered. Whatever behavioral patterns of the whales that existed before the 2000s may remain unknown as there’s evidence where they are feeding is changing.

Davis says the whales are spreading out where they live and feed, venturing further up and down the Atlantic coastline. It’s possible they’re following zooplankton, their main source of food. Share on X

But a lack of background knowledge on right whales is inhibiting scientists from saying for certain, which is what catalyzed the research in the first place. The groups working to learn more eventually collaborated in 1986 and formed the North Atlantic Right Whale Consortium.

Those involved in the current acoustic study have been aided by NOAA, WHOI, and Maine’s Department of Marine Resources.

“When researchers realized North Atlantic right whales were in such trouble and the only way to help save the species was to work together, many organizations came to form this consortium, which now houses one of the most extensive datasets on any one species,” Davis said. “We have an annual meeting every year where it’s like an open science symposium to learn about all the research going on, and the status of how those projects are doing, and to discuss conservation goals to help the right whales’ recovery.”

0 comments