Northeast Pacific Acidification From Anthropogenic Carbon Calculated

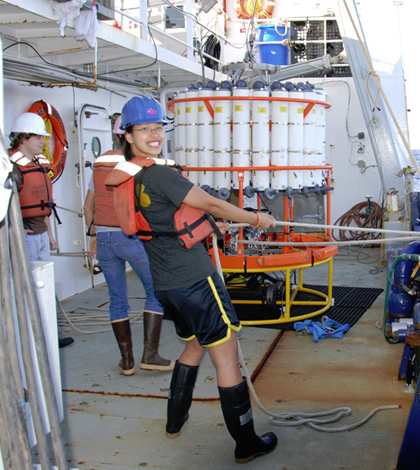

Sophie Chu, graduate student in MIT’s Department of Earth, Atmospheric, and Planetary Sciences, stands in front of a rosette for measuring conductivity, temperature and depth. (Zhaohui Aleck Wang / Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

Scientists at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution have measured the rate of acidification for the northeast Pacific Ocean. Their data, gathered through a research expedition, show the impacts that carbon from human activities is having on the area.

Investigators found that most of the anthropogenic carbon in the northeast Pacific has lingered in the upper layers, changing the chemistry of the ocean as a result. In the past 10 years, the region’s average pH has dropped by 0.002 pH units per year, leading to more acidic waters. The rise in carbon dioxide has also decreased the availability of an essential mineral that many marine species rely on in forming their protective shells.

To make the find, the team embarked on a scientific cruise to the northeast Pacific in 2012. There, they followed the same route as a similar cruise in 2001. During the month-long journey, researchers gathered samples of pteropods (pelagic sea snails) as well as seawater. This was analyzed for temperature, salinity, and pH.

After bringing the water samples and specimens back to the lab, investigators realized that their data could also be used to gauge the region’s changing carbon storage. It’s more difficult than it sounds, as the scientists had to separate the carbon that was contributed by humans from that originating from the northeast Pacific Ocean itself. Both types are classified as dissolved inorganic carbon and the amount of anthropogenic carbon in oceans is miniscule compared to the amounts that have accumulated there naturally over millions of years.

To isolate anthropogenic carbon and observe how it has changed through time, investigators used a modeling technique to look at the relationships between many variables. The model was run for each year between 2001 and 2012, including the measurements of water temperature and salinity, among other metrics. It then estimated the natural variability in dissolved inorganic carbon for each year.

The model gave scientists a nice estimate of the amount of carbon in the northeast Pacific Ocean year by year and how it would typically vary based on natural processes. They were able to subtract that from another estimate of carbon variability that included human contributions.

Full results of the effort are published in the Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans.

Top image: Sophie Chu, graduate student in MIT’s Department of Earth, Atmospheric, and Planetary Sciences, stands in front of a rosette for measuring conductivity, temperature and depth. (Zhaohui Aleck Wang / Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

0 comments