Northeast Stream Quality Assessment Gears Up For 2016

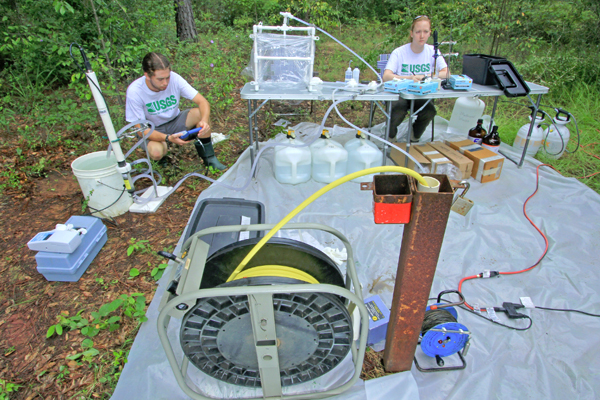

Researchers with the National Water Quality Assessment collect a water sample in the Northeast U.S. (Credit: U.S. Geological Survey)

In the first few days of June, scientists with the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) have begun taking samples as part of the Northeast Stream Quality Assessment. The research effort is part of a broader program, the National Water-Quality Assessment, that began in 1991 to assess the water quality changes impacting streams in the United States.

“It grew out of questions in the 1980s that Congress was asking the USGS, asking if the water quality of the nation’s streams was getting better or worse,” said Peter Van Metre, research hydrologist and coordinator for regional stream quality assessments with the agency. “The director (at the time) had to admit that data weren’t collected at a large-enough scale to say.”

From there, the program has grown and included long-term, systematic monitoring at streams across the country and many regional assessments of stream water quality. Each decade, it goes through a re-design to make sure that it’s hitting on the more pressing issues facing stream quality in the U.S.

In recent years, Van Metre and other scientists have wrapped up investigations in the Midwest, Southeast and Pacific Northwest regions of the country. Those have revealed some interesting finds.

“We know that urban development and agriculture can harm the health of streams, but to change that, to mitigate those effects, we need a better understanding of the specific factors that harm aquatic life,” said Van Metre. “That’s the objective of the regional stream quality assessments that the USGS started in 2013.”

Sampling surficial aquifer wells across the coastal plain of Georgia, and adjacent Alabama and Florida. (Credit: Alan Cressler / U.S. Geological Survey)

Specifically in the Southeast, including states like Georgia, North Carolina and Virginia, researchers found pharmaceuticals in all 59 of the streams that they sampled. These are known to come from wastewater treatment plants, but the substances were still present in 42 of the waterways without any treatment plants nearby. Van Metre says that the pharmaceuticals found in those streams are likely from aging urban sewers and rural septic systems.

But pharmaceuticals are just one thing that gets considered in the stream quality assessments. Data are also collected on algal toxins, sediments, invertebrates, mercury levels in fish, and more than 200 pesticide chemicals, among other things.

Following the assessment in the Midwest region, for example, scientists noted the highest nitrate levels ever measured in some streams. The greatest levels were found in Iowa, followed by southern Minnesota and central Illinois.

Measurements from monitoring networks are thrown in. And there are also ecology surveys that document habitat and a region’s creatures.

“We’re only doing wadeable streams. They’re not much more than 3 feet deep. Most have watershed areas of 100 square miles or less,” said Van Metre. A good example of this in the Northeast assessment’s case is the Bronx River, which is only 24 miles long. “What we’re really interested in doing is sampling the stressor conditions — pesticides, erosion, habitat variables. We don’t know all that upfront, so we select sites with a range of land uses.”

Some of the tools that will be used for the work in the Northeast, also used in the other assessments, include discrete water sampling gear. Teflon churns are used to composite, or mix, some of the samples. Many of these are analyzed by a mass spectrometer that can quantify what they contain down to parts-per-trillion levels.

Sampling water from a well developed in the Upper Floridan Aquifer as part of the U. S. Geological Survey’s National Water Quality Assessment. (Credit: Alan Cressler / U.S. Geological Survey)

As part of the ecology survey planned for near the end of the assessment, electrofishing gear will be used to stun fish for study, nets will help to gather invertebrates and small brushes will help scientists scrape algae off rocks.

“We’re also collecting sediment samples to check for toxicity in a lab. We’re mapping the habitats of stream reaches, looking at geometry, substrate and all the things that affect ecology there,” said Van Metre. “We’re keeping some of the fish to analyze for mercury and using different isotopes of mercury to tell us about sources like atmospheric deposition from coal plants.”

Across all 95 of the sites involved in the Northeast Stream Quality Assessment, Van Metre says algal toxins will be tracked. And data from remote monitoring sites will also kick in some insights. The sites will be segmented for study, with 59 of the more urban sites getting sampled for nine weeks and the remaining ones, which are more forested and underdeveloped, for just four weeks.

It’s too early for speculation on what the assessment will uncover (it wraps up in August), but there are some expectations given the Northeast’s makeup.

“We are going to areas that have the biggest human footprint. The Midwest, Northeast and Southeast all have large urban centers and urban sprawl,” said Van Metre. “With such intense urbanization, we expect to see a big range of contaminants.”

But one big-picture takeaway is clear to Van Metre, who has had a hand in many stream quality assessments.

“We’re starting to evaluate the effects of stressors on ecology. Our modelers relate stressors to ecological communities. Our results suggest we should be asking how many different stressors that we see,” said Van Metre. “You can have individual stressors but as we see more and more combine, you begin to really see degradation of ecological communities.”

Top image: Researchers with the National Water Quality Assessment collect a water sample in the Northeast U.S. (Credit: U.S. Geological Survey)

0 comments