Ohio regulators still working to understand algal toxicity

Algae infested Grand Lake St. Marys in Ohio in 2010. As the bloom died, animals and people started getting sick from the waterborne microbes.

In an extreme case, toxins produced by algae in the lake killed a Labrador retriever and landed dog owner Danny Jenkins in the hospital. “He washed the dog. (Water) splashed in his face and he ended up with some neurological issues,” said Linda Merchant-Masonbrink, coordinator for the Ohio Environmental Protection Agency’s inland lakes and harmful algal blooms workgroups. “So it does happen, but not very often.”

Several forms of algae dwelling in Ohio and water bodies across the nation have the potential to produce toxins that can cause skin irritation, liver poisoning and brain damage. Ohio regulators are still in the early stages of understanding how to keep the public safe from algal toxins.

“Toxins are tasteless and odorless and they’re water soluble,” said Merchant-Masonbrink. “So the public can’t see it. We’re going to have to talk to the public about things they can’t see, smell, taste or whatever. So that’s a bit of a problem.”

The Ohio EPA and departments of Natural Resources and Health work together to sample and monitor for algae in inland lakes in state parks. Their methods are still developing to deal with the variable nature of algae toxin release.

Algal toxins are typically contained inside cells until they die, breaking open the cells and releasing toxins. The concentration and length of time the toxins persist depends on how the algae grow and how the lake mixes.

Jeff Reutter, director of Ohio State University’s Stone Laboratory, said Lake Erie’s rapid mixing, for instance, lowers the potential for severe danger from algal toxins after a bloom passes. “The mixing and the movement that we have here is going to rapidly reduce that toxin concentration to the point that it’s no longer a serious problem,” he said. “In the smaller bodies of water I would be a whole lot less confident in making any kind of a statement that way.”

Merchant-Masonbrink said she cannot say generally how long toxins persist after a bloom disappears because there are too many variables at play in any given water body.

Microcystin is the most common toxin, found in 30 percent of inland lakes nationwide, according to the U.S. EPA’s national lakes survey. It’s a liver toxin produced by the blue-green algae species microcystis. Symptoms of microcystin exposure include vomiting, diarrhea, liver tumors and even death. So far, death after exposure has only been reported in animals in Ohio.

Merchant-Masonbrink said she thinks microcystin exposure is underreported. “Some people go to the lake to go swimming, they take their picnic, and they start vomiting after they’ve been swimming and ate a little bit,” she said. “Well we think that a lot of this is underreported because people are attributing it to the bad potato salad that they had in their lunch or the alcohol they were drinking.”

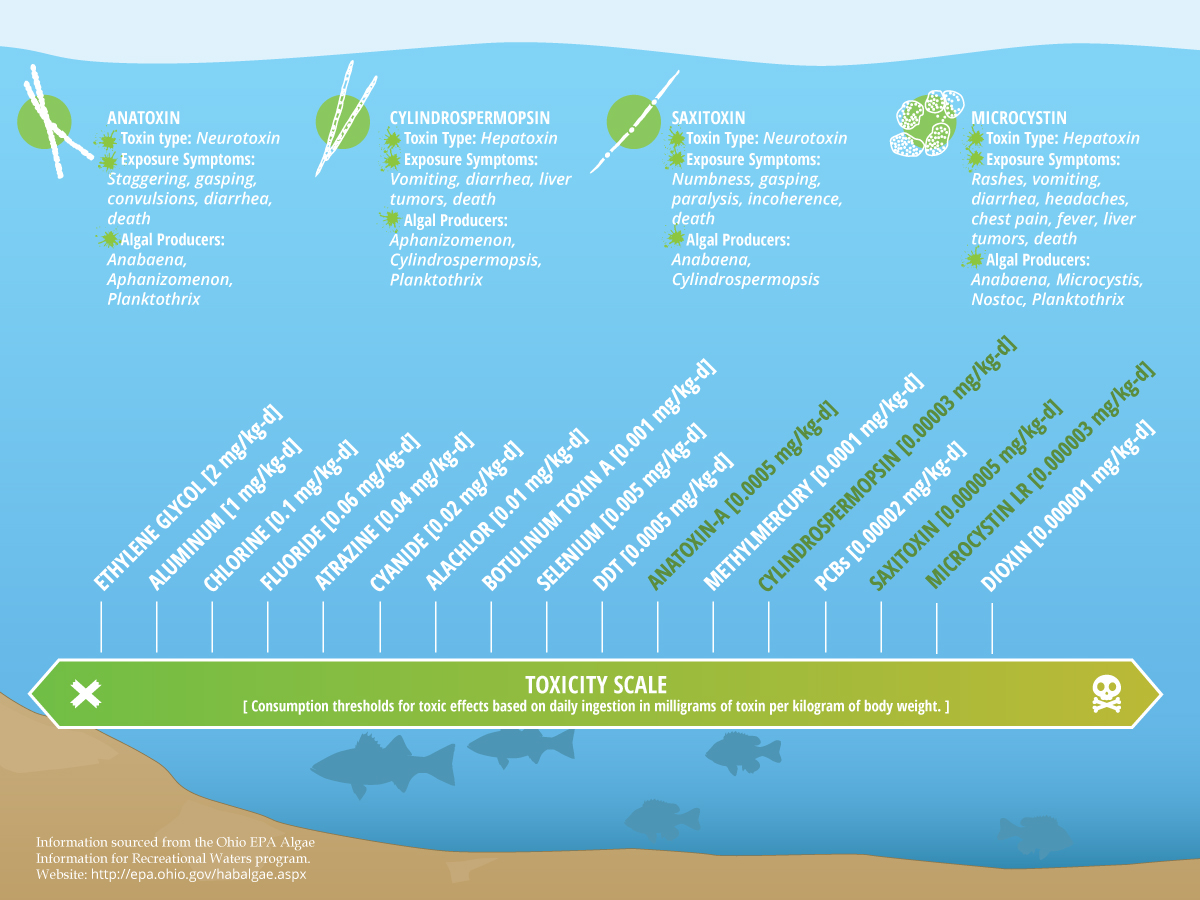

Two forms of algal neurotoxins, anatoxin-a and saxitoxin, can also be found in U.S. lakes. Saxitoxins are commonly associated with paralytic shellfish poisoning and can have the same paralytic effect on humans if ingested in high enough dosage. Anatoxin-a has been called “Very Fast Death Factor” due to its quick killing potential from respiratory paralysis when one ingests a lethal dose.

Toxicity of algal toxins compared with other substances. Click to expand. (Credit: Nate Christopher)

Algal toxins are mainly a threat in recreational waters. Tests of finished water at drinking water plants rarely show levels of algal toxins. “Really, what we’ve seen so far is that the water suppliers are adequately treating the water so that we’re not getting those toxins in the finished water,” said Merchant-Masonbrink.

Algae are separated out by a water treatment plant’s solids removal processes before the cells can break down and release toxins. Toxins that make it through are usually removed by chemical treatment later in the cleaning process.

As for swimmers and water sport participants, there is currently no way to test for toxins before taking a dip. Ohio EPA alerts people to algal blooms and their latest testing results, but only covers state park lakes where workers have witnessed blooms.

A method for testing for some algal toxins may be on the market within a few years. The VTT Technical Research Centre of Finland, a non-profit research institute, has developed a novel on-site algal toxin test. “(The) test is based on antibodies that detect the presence of algal toxins,” said Liisa Hakola, a VTT Senior Scientist who worked to develop the test.

The test has been verified to detect microcystin and can reliably detect it at 40 parts per billion, double the World Health Organizations suggested threshold for recreational water use. Hakola said the test can detect microcystin at 20 parts per billion, but the accuracy at that level is still in question.

Cost for the test should be relatively low as mass production costs less than $1.50 per test. Hakola said VTT is working to find partners to commercialize the test. It may make it to the U.S. depending on VTT’s partners.

For now, Merchant-Masonbrink said people should remember that if they see a bloom at their local swimming hole, “When in doubt, stay out.”

For more information on algae in Ohio, see the Ohio EPA’s algae information for recreational waters website.

Top image: Lake Erie algal bloom 2011 (Credit: Brenda Culler / Ohio Department of Natural Resources)

0 comments