Phreatic Eruptions Follow Changes In Gas Composition

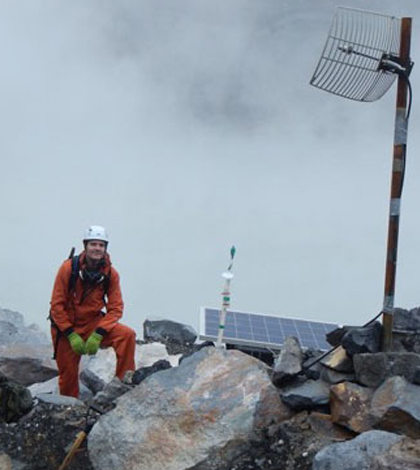

University of New Mexico Department of Planetary Sciences Professor Tobias Fischer at Poas Volcano in Costa Rica. (Credit: University of New Mexico)

Phreatic eruptions from volcanoes are steam-driven explosions that occur when water beneath the ground or on the surface is heated by magma, lava, hot rocks or new volcanic deposits. But despite the fact that scientists understand how the eruptions occur, that doesn’t make them any easier to predict.

Such is the case for the crater lake in the Poas Volcano in Costa Rica. In 2014 alone, the volcano experienced more than 60 phreatic eruptions ranging from minor gas bursts to highly explosive jets ejecting sediments, vapor and lake water to more than 400 meters above the lake surface.

These eruptions are clearly dangerous and chase visitors away from the Poas Volcano National Park, the home of the mountain. Because of that, as well as scientific interest, researchers from the University of New Mexico set out to see if there was any way to predict when the volcano is most likely to have phreatic eruptions. They focused on the volcano’s gases to investigate.

Their primary goal was to quantify gas fluxes, including those of carbon dioxide, sulfur dioxide and hydrogen sulfide, from Poas Volcano and to monitor changes in gas compositions. From there, the scientists were also looking to monitor degassing to track volcanic activity and find ways for mitigating the hazards caused by eruptions.

Many have thought that phreatic eruptions were primarily generated by changes in hydrothermal systems with really no other precursors. But the results of the study, published in the journal Earth and Planetary Science Letters, show that there are short-term changes in gas compositions prior to phreatic eruptions at Poas Volcano. These appear to be caused by short-period changes in superheated volcanic gas from the deep magmatic system.

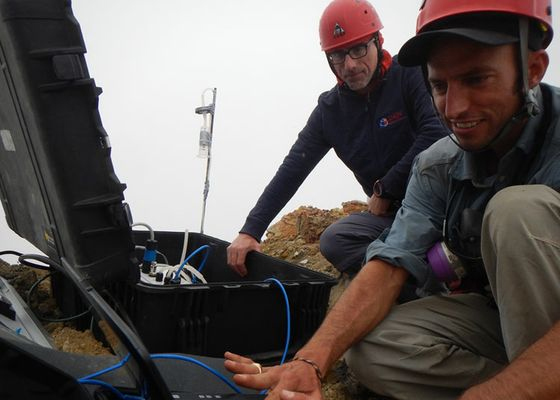

Researchers measure gas emissions from crater lake at Poas Volcano in Costa Rica in an attempt to determine some of the precursors to phreatic eruptions. (Credit: University of New Mexico)

During a two-month period of phreatic activity in 2014, the researchers measured gas emissions from the crater lake using a fixed multiple gas analyzer station, or Multi-GAS. The instrument measures gas ratios, such as those between sulfur dioxide and carbon dioxide or hydrogen sulfide. Precision, or reproducibility, is one of the things that scientists look for with Multi-GAS measurements.

The gas composition data showed significant variations in the ratios between sulfur dioxide and carbon dioxide, which are statistically correlated with both the occurrence and size of phreatic eruptions. The scientists found that the composition of gas emitted directly from the lake approaches that of magmatic gas days before large phreatic eruptions.

Researchers think that the changes in gas chemistry are due to the susceptibility of different gas species to reaction with hydrothermal fluids. For carbon dioxide, it is inert in ultra-acidic conditions and passes through the hydrothermal system and acid lake without getting changed much. But sulfur dioxide is different in that it’s partially removed from the gas phase by hydrothermal reactions.

Using another instrument, called a mini-DOAS, investigators confirmed that high emissions of sulfur dioxide from the crater lake took place during eruptive activity and are also associated with a high ratio of the gas to carbon dioxide.

The results show that high-frequency gas monitoring may provide an effective means of forecasting phreatic eruptions. But the biggest challenge to that monitoring approach is maintaining the instruments. Researchers saw this firsthand, as several components were destroyed by a large eruption in June 2014 that meant the end of the emission experiment.

Scientists from the Deep Carbon Observatory and the University of New Mexico collaborated in the work.

Top image: University of New Mexico Department of Planetary Sciences Professor Tobias Fischer at Poas Volcano in Costa Rica. (Credit: University of New Mexico)

0 comments